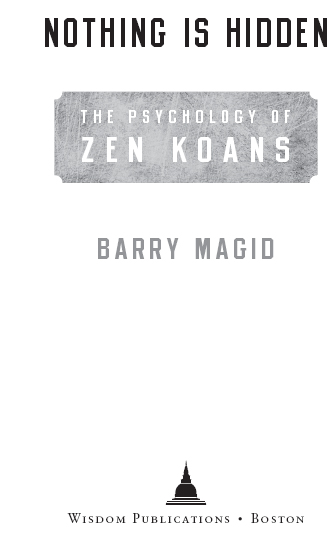

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2013 Barry Magid

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Magid, Barry.

Nothing is hidden : the psychology of Zen koans / Barry Magid.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-61429-082-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Zen BuddhismPsychology. 2. Koan. I. Title.

BQ9265.8.M34 2013

294.3927dc23

2013000339

ISBN 978-1-61429-082-7

eBook ISBN 978-1-61429-102-2

17 16 15 14 13

5 4 3 2 1

Cover design by Phil Pascuzzo. Interior design by Gopa&Ted2, based on a design by DC Design. Set in Sabon LT Std 10.5/15.5. Author photo by Peter Cunningham.

Song in the Manner of Housman by Ezra Pound, from COLLECTED EARLY POEMS, copyright 1976 by The Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 12 trees, 6 million BTUs of energy, 1,064 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 5,770 gallons of water, and 380 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 12 trees, 6 million BTUs of energy, 1,064 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 5,770 gallons of water, and 380 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

IN MEMORIAM

Charlotte Joko Beck

(19172011)

CONTENTS

Both as a student and a teacher, I have had a complicated relationship to koans, one that perhaps mirrors many of the twists and turns of their use in America. As a Dharma heir of Charlotte Joko Beck, I belong to a Zen lineage that contains elements of both Rinzai and Soto practices, the two primary traditions of Japanese Zen. Rinzai Zen is usually identified with koan practice; the student typically starts with a initial koan like Mu and then moves through a sequence of koans centered on the canonical collections, among which are the Gateless Gate and the Blue Cliff Record, which were assembled almost one thousand years ago. Soto Zen is grounded in shikantaza or just sitting, a form of practice established in Japan by Eihei Dogen in the thirteenth century. Dogen also used koansor at least gave numerous talks based on koansbut teachers in the Soto lineages typically did not use them in the systematic, question-and-answer way that characterized the Rinzai lineages as revived by the renowned master Hakuin in eighteenth-century Japan.

Although there are pure Rinzai and Soto lineages in America, the lineage I belong to is a hybrid of the two, as indeed are most Zen lineages in America. This fact is largely due to the influence of a single remarkable teacher, Hakuun Yasutani (18851973). Yasutani started off as monk in the Soto Zen tradition, studying under a teacher who was considered one of the greatest Dogen scholars of his day, Nishiari Bokusan. But as a young monk, Yasutani was disillusioned by what he saw as the complacency of his fellow monks.

Their great founder Eihei Dogen (12001253) had taught that Zen meditation was not a means to an end, not a technique for achieving enlightenment, but that practice and realization were inseparably one and the same. Dogen wrote, The zazen I speak of is not meditation practice. It is simply the Dharma gate of joyful ease, the practice-realization of totally culminated enlightenment.

However, Yasutani thought that what he saw around himself in the monastery was neither joyful nor enlightened and that the true spirit of Dogen was missing from Nishiaris Zen. His condemnation of his teacher was harsh:

Beginning with Nishiari Zenjis, I have examined closely the commentaries on the Shobogenzo [Dogens master-work] of many modern people, and though it is rude to say it, they have failed badly in their efforts to grasp its main points. It goes without saying that Nishiari Zenji was a priest of great learning and virtue, but even a green priest like me will not affirm his eye of satori [enlightenment]. So it is my earnest wish to correct to some degree the evil [of Nishiaris theoretical Zen] in order to requite his benevolence, and that of his disciples, which they have extended over many years.

Yasutani left Nishiaris monastery, married, and became an elementary school teacher. He nonetheless continued his practice with a number of different teachersuntil he met Harada Sogaku Roshi.

Harada also had been a Soto priest, whose own search had brought him to study with Toyota Dokutan (18411919), abbot of Nanzenji, a Rinzai temple. Harada completed koan study with him and become his Dharma successor, though he formally remained a Soto priest, eventually becoming abbot of Hosshinji, a Soto temple. Yasutani sat his first sesshin with Harada in 1925 and two years later at the age of forty-two was recognized as having attained ken-sho, an initial experience of enlightenment. Ten years later, at the age of fifty-eight, he finished his koan study and received Dharma transmission from Harada Roshi on April 8, 1943.

Yasutani first came to the United States in 1962, at the invitation of Philip Kapleau, who had studied with Harada Roshi at Hossinji. Kapleau, whose book The Three Pillars of Zen introduced many of my generation of Americans to Zen practice, went on to be the founder of the Rochester Zen Center. Other students of Yasutani were Robert Aitken and Taizan Maezumi, each of whom went on to establish flourishing American lineages. Yet while I would eventually train and receive Dharma transmission in Charlotte Joko Becks branch of the Yasutani-Maezumi lineage, my first experience of Zen was with the Rinzai teacher Eido Shimano, whose own mixture of charisma, insight, and sexual misconduct provided a whole generation of American Zen students with their first true koan. In many important ways, this and my previous books have been attempts to keep working on that first koan: the relationship of realization to personal character and psychology, how the two intersect, or how, all too often, they can instead be like two arrows missing in midair.

When I came to New York City in 1975, after medical school, to begin my residency training in psychiatry, I began looking for an analyst and looking for a place to begin practicing Zen. Eidos Zen Studies Society appeared to be the only game in town as far as Zen went; the options for psychoanalytic training were far more diverse and complicated.

In those days, it felt like my psychoanalytic world was divided into two camps, the followers of Heinz Kohut and the followers of Otto Kernberg. The world of psychoanalysis was obviously far more complex than that, with Freudians, Kleinians, Sullivanians, Horneyans, Jungians, and Winnicottians all competing for attentionnot to mention the popular nonanalytic offshoots of Gestalt and Transactional Analysis.

Next page

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 12 trees, 6 million BTUs of energy, 1,064 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 5,770 gallons of water, and 380 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 12 trees, 6 million BTUs of energy, 1,064 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 5,770 gallons of water, and 380 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.