TEACHING THE

ALEXANDER

TECHNIQUE

Active Pathways to Integrative Practice

CATHY MADDEN

Contents

Introduction

How did you think of that? is the question I am most often asked when I am teaching. Each time I am asked, I answer it as completely as I can. And, however I answer, there is a subterranean pastiche of experience and skills and beliefs that created the idea appearing at that moment in time. As with talking about anything and everything Alexander Technique-related, I wish for a tongue that could say many things at once when asked to explain where an idea came from. These writings collect the influences, skills, and experimentation that create the act, perhaps the art, of teaching the Alexander Technique.

The movement through the book begins with acknowledging, in Part One, the background and training shaping my perspective on the Alexander Technique. Part Two of the book considers the essential skills in teaching, with Teaching Stories contributed by students and colleagues offering examples of specific lessons. In Part Three, I offer theoretical background related to my teaching practice, including acting training, studies in adult education (andragogy), and research on human performance and creativity, as well as input from everyone who has ever studied with me. Initially, these theories helped me explain what I was already doing; now, knowing them, they further develop my skills. This part moves into practical application of the accumulated skill sets and ideas in a wide variety of teaching situations. A glimpse into a myriad of games possibilities and a variety of teaching tips provide resources. I close with wishes on the future of teaching this work.

My hope is that the whole book is both a teaching text and teaching resource. While there is a logic to its sequence of chapters, you could drop into any chapter if there is something specific you need or are interested in. (You might need to check in on the Cathy Glossary in Chapter 2 if you drop into the middle of the book, as I have a propensity to make up words and terms.)

The references offered within the text aim to acknowledge the many fields that contribute to evolving the understanding and teaching of the Alexander Technique. While the book is intended for people who are teaching the Alexander Technique, the truth is that, ultimately, all of us must teach ourselves this elegant process. For anyone reading this as a student of the Alexander Technique, the ideas in this book offer you an opportunity to take on that role of teacher for yourself.

My hope is that each person who reads this is inspired to think of the stories and ideas that they would add to each of the chapters. Each of us is ultimately the evolutioner of our own development.

Part One

MY JOURNEY TO

TEACHING THE

ALEXANDER

TECHNIQUE

Chapter 1

MARJS LIVING ROOM

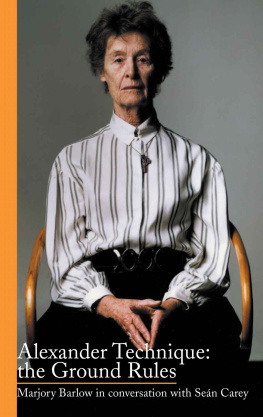

Walking on a beach in Maine with a friend, I mentioned something about being an Alexander Technique teacher; he gently, kindly contradicted me: You are a teacher. The Alexander Technique is the practice guiding your teaching. This is the spirit and perspective that animates this bookcommencing with acknowledging my source and inspiration, my Alexander Technique teacher-mentor Marjorie Barstow (18991994, hereafter referred to as Marj).

While I was working on my Masters degree in Theatre at Washington University in St. Louis, Professor of Theatre Sid Friedman invited Marj to give a workshop. He had studied with her at a summer theatre movement workshop and told me, I think youd like it. In the acting studio at Edison Theatre, Marj introduced the Alexander Technique to a circle of 20 or so university students. What I remember from that first day was how she moved, talked, taughtand piqued my curiosity. I was particularly fascinated by the increase in theatrical presence I experienced in watching my fellow actors. As we had shared classes for a year, I was familiar with their movement and sound. Something happened in these lessons, however, that invited me to be with them in a way I hadnt experienced before. Fortunately, Sid invited Marj to the university multiple times over the course of my program.

I knew Marj was considered one of the best Alexander Technique teachers in the world, had studied with F.M. Alexander himself, and lived in Lincoln, Nebraska. From Sid, I learned that people learned to teach the work through studying with her. This was the entirety of my research about Alexander Technique teacher training. I wrote Marj a letter saying that I would like to move to Lincoln and learn how to teach with her. Would that be okay? I received a note back (how I wish I had kept it!): Why dont you come along and see what happens? And so I moved to Nebraska.

At the time, Marj taught two large workshops per year (summer and winter) and held classes twice weekly at her house, usually from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. I attended as often as I could, all the while acting, directing, and working a day job. These classes formed the foundation of my learning. The format for these workshops and classes was primarily turn-based; that is, if you had something you wanted to do, you raised your hand and asked for a turn. Walking, singing, reaching for things, dancing, running, sewinganything you wanted to explore.

Living Room tude

What follows is a description of the journey by which I became the teacher I am today. This is also the core of how I choose to teach people to teach.

Marj did not treat learning to teach any differently than experimenting with your walking. Teaching was just another activity, and if you wanted to learn to do it, you asked to teach for your turn in class. The first time I ventured I would like to teach was a benchmark moment. I wish I could say that I specifically remember raising my voice to take this step. I dont. What I do remember are the many times I had wanted to say this and didnt. Believing that I had developed enough skills to take on this task took me quite a while. One day, my desire to learn to teach became stronger than my fear of failure.

The act of learning to teach begins with your volition, your desire. Marj didnt care if you taught, and she would happily provide you with the tools you needed if you wanted to teach .

Any time I asked to teach, the atmosphere in the room shifted. Marj sat down and looked expectantly in my directionturning the teaching space over to me.

If you asked to teach for your turn, Marj, by sitting down, was telling you that you were now taking full responsibility for your own coordination.

My first job was to find someone who wanted to be my student.

In taking on this task, you changed your role, your relationship to the people in the room, and your responsibility to the people in the room. No in between existedno sort of or practice teachingyou were now the teacher.

Next, as I intended to start the lesson, Marj would ask, What do you notice about yourself? When I could answer this question clearly, using what I knew to address any concerns constructively, she invited me to resume. If I got stuck in some way, shed say, Why dont you think about that for a while?

What potent messages she put in this simple, elegant learning experience! As a teacher, your ability to coordinate is your own responsibility. Your job is to thinkto analyze and solve your own dilemmas. She didnt help you get unstuck, but, rather, offered the respect of knowing that you could figure it out for yourself. She often reminded us, The teacher is the most important person in the lesson, and your first job was to be using the Alexander Technique yourself. Questions about the student came next, but only after you were fully using what you knew in service of your own coordination.

Next page