ARCHITECTURE AT THE END OF THE EARTH

Photographing the Russian North

TEXT AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY

William Craft Brumfield

DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS

DURHAM AND LONDON

2015

2015 Duke University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Designed by Heather Hensley

Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brumfield, William Craft, 1944

Architecture at the end of the earth : photographing the Russian North / text and photographs by William Craft Brumfield.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8223-5906-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8223-7543-2 (e-book)

1. ArchitectureRussia, Northern. 2. ArchitectureRussia, NorthernPictorial works. 3. Russia, NorthernDescription and travel. 4. Russia, NorthernPictorial works. I. Title.

NA1195.N57B78 2015

720.9471dc23 2014046255

Frontispiece: Varzuga. Church of the Dormition of the Virgin (1674), northwest view above right bank of Varzuga River. Photograph: July 21, 2001.

Cover: Kimzha. Church of the Hodegetria Icon of the Virgin, southwest view.

Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Richard Hedreen, who provided funds toward the publication of this book.

IN MEMORY OF

Tamara Kholkina

(September 30, 1955August 1, 2009)

Blessed are the pure in heart...

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Exploring the Russian North

INTO THE FOREST

A Note on the Architectural Heritage of the Russian North

POSTSCRIPT

What Will Remain of the Heritage of the Russian North?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The journey through the Russian North that I present in this book has unfolded over many years. During that period I have experienced the generosity of many individuals and organizations, both in the United States and in Russia. I will not attempt to place order on my memory; rather, the names are listed as they come to me: Dr. James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress, for many years of interest in my work and for providing the support that sent me to so many remote corners of Russia; Dr. Dan E. Davidson, president of American Councils for International Education, who has done so much to keep me in the field; Dr. Blair A. Ruble, formerly director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies in Washington, who supported many publications of my fieldwork. Tulane University has over the years provided the essential base for my work. Specific projects and periods in the Russian North have been supported by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the National Humanities Center, the National Endowment for the Humanities (with their excellent magazine Humanities), the National Council for East European and Eurasian Research, and the American Councils for International Education. Special thanks are due to the Photographic Archives (now Image Collections) at the National Gallery of Art, which has housed the basic collection of my photographic work since 1985 with the steady guidance of curator Andrea Gibbs.

In Russia I am daunted by the challenge of acknowledging the generosity of so many people, a number of whom are no longer with us: Dr. Aleksei I. Komech, directorof the State Institute of Art History during critical years of my work in the 1990s until 2007; colleagues at Pomor State University (now renamed Northern Arctic Federal University) in Arkhangelsk; Nelli Belova, for many years director of the Vologda Regional Library; Oleg Samusenko and Olga Bakhareva, friends in Cherepovets; Father Andrei Kozlov and his family (St. Petersburg). And to Moscow colleagues at the website Russia Beyond the Headlines for their supportive interest in my work over the past half decade.

The book itself would not have been possible without the extraordinary generosity and friendship of Richard and Betty Hedreen. In 2004 their support made possible a new edition of my fundamental work, A History of Russian Architecture. And now the Hedreens have enabled this present work with the dedicated professionals at Duke University Press, with whom I have had a productive relationship going back to the 1990s, when Duke published my Lost Russia: Photographing the Ruins of Russian Architecture. At the press I owe a special debt to the editor of this book, Miriam Angress.

The journey continues.

Introduction

Exploring the Russian North

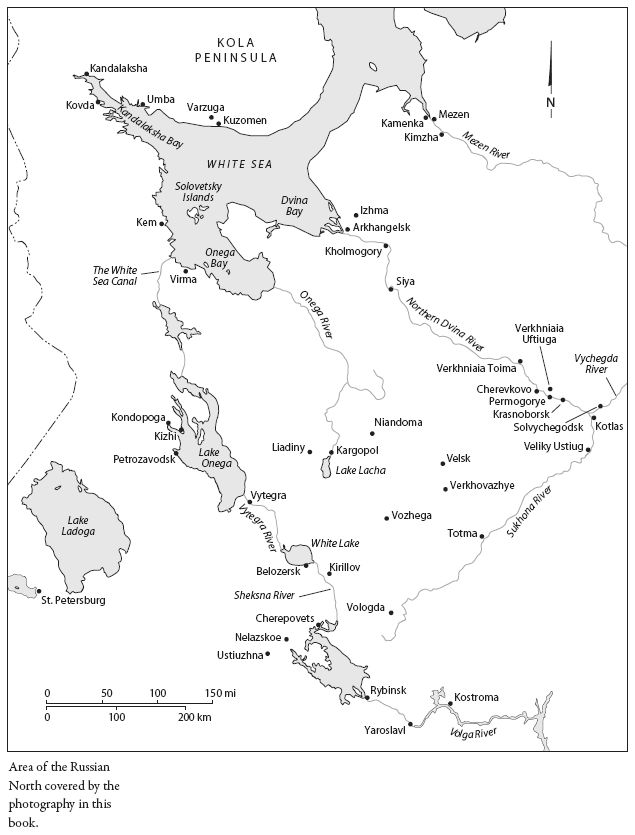

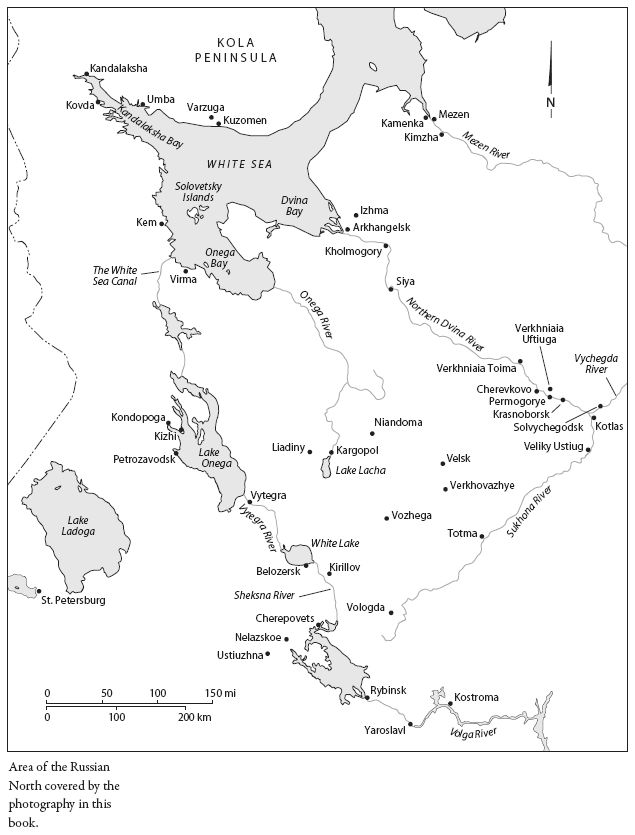

In the popular imagination, virtually all Russia is north, cold and imponderable. Yet within this immense Eurasian landmass, there is a region traditionally known as the Russian North that includes territories located within or near the basin of the White Sea. This space is crossed by water networks extending from the White Lake (Beloe Ozero) to the White Sea (Beloe Morye). (The names themselves speak volumes.) Of special interest are the contemporary regions of Vologda and Arkhangelsk. Despite the cataclysms of the twentieth century, this area of the Russian North still lays claim to a deeply rooted cultural coherence created by those who settled in its forests and moved along its rivers and lakes.

Today, the rivers have silted, and travel in the north occurs by roador what passes for a road. The vehicle is all. The new Russians have their Mercedes and Cherokees, but for the true connoisseur of the Russian road, the ultimate machine is the UAZIK, Russias closest equivalent to the classic Jeep. Four-wheeled drive, two gear sticks, two gas tanks (left and right), taut suspension, high clearance. Seat belts? Dont ask. The top speed is one hundred kilometers per hour, but you rarely reach that if you drive it over the rutted tracks and potholed back roads for which it was designed.

No place in Russia has more of such roads than Arkhangelsk Province, a vast territory that extends from the White and Barents Seas in the north to its boundary with Vologda Province to the south. A combination of poverty, government default on both a local and national level, and distances that exceed those of mostwestern European countries have created some of the worst roads in European Russia.

Hence the UAZIK, whose name derives from the acronym for Ulyanovsk Auto Factory, located in the city of Ulyanovsk on the Volga River. Comfortable it is not, but an experienced driver can take this machine over rutted ice tracks in the middle of a snowstorm and not miss a beat. I should say at the outset that I am not such a driver, and I have only a vague idea as to how the machine works. I am, however, fluent in the Russian language, and that ability rescued many a challenging situation.

Although my first photographs of Russia were taken during the summer of1970, my first limited foray to the North did not occur until 1988 (Kizhi Island), with return trips to the same area in 1991 and 1993. My deeper exploration of the area began only in 1995, but over the preceding two and a half decades I had created a substantial photographic archive and published fundamental books on Russian architectural historyincluding A History of Russian Architecture (1993, with a second edition in 2004). By the time physical and bureaucratic obstacles to travel in the North were overcome, I was prepared to see this area as an expression of time-honored traditions that I had long studied. After research came the road trips, and the drivers got me where I needed to go. My job was to keep the cameras ready and scan the horizon for onion domes. And in my travels throughout the North, the UAZIK performed superbly with or without roads.