Contents

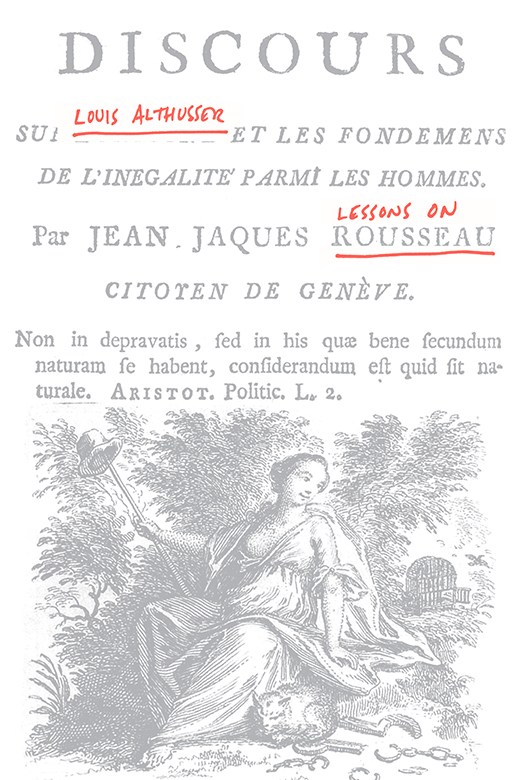

LESSONS ON ROUSSEAU

LESSONS ON ROUSSEAU

Louis Althusser

Edited with an Introduction by Yves Vargas

Translated by G.M. Goshgarian

This book is supported by the Institut franais (Royaume-Uni)

as part of the Burgess Programme

Cet ouvrage publi dans le cadre du programme daide la publication bnficie

du soutien du Ministre des Affaires trangres et du Service Culturel de

lAmbassade de France reprsent aux tats-Unis. This work received support from

the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French

Embassy in the United States through their publishing assistance program.

First published in English by Verso Books 2019

First published as Cours sur Rousseau

ditions Le Temps des Cerises 2012

Translation G.M. Goshgarian 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-557-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-556-7 (HBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-559-8 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-558-1 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947020

Typeset in Garamond by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

T HE TEXT THAT FOLLOWS is a faithful transcription of a course that Althusser gave in 1972 at the Paris cole normale suprieure for students preparing to sit the agrgation. It is based on a tape recording made with Althussers permission; he agreed to have a microphone placed on his lectern. Only a few words have been left out of the transcription: words that mark a hesitation (well, uh, and so on), repetitions of the same word, and a few bits and pieces of sentences that were lost because a few seconds were needed to change the audio cassette. The reader may consult the original recording, which has been made available to the public by the Fondation Gabriel Pri.

Reading the courses edited by Franois Matheron and published by Le Seuil under the title Althusser, Politique et histoire, I was struck by the thought that this tape recording, which had been slumbering in my drawer for forty years, might serve as a source of ideas, suggestions for further research, and new knowledge not to be found in Althussers 1956 and 1966 courses on Rousseau. That led to the deposit of the audio cassettes with the Fondation Gabriel Pri and publication of the present volume.

T O TALK ABOUT A PHILOSOPHER who explains another philosopher is a paradoxical enterprise. Should one explain an explanation?

There should thus be no mistake about the objective of this introduction. Those who know Rousseaus texts well enough can read Althussers course directly, and the same holds for those familiar with Althussers thought.

The present introductory notes are meant for readers who are curious and attentive, but are not specialists, know the one philosopher and the other only by way of a few quotations or by hearsay, and might be discouraged by the rather abstract nature of the course or wearied by its repetitive features, forgetting that what is involved is a course intended for students taking notes, not a lecture intended for a public interested in acquiring information quickly. We have therefore extracted a few basic themes from the course, a few noteworthy original ideas, in order to provide a guide to a reading of it with the help of a few signposts, a few words, expressions and arguments that we have thrown into relief.

We have also attempted to reassess these remarks on Rousseau which seemed remote, at the time, from Althussers preoccupations with Marxism by setting them in relation to his posthumous texts. Talking about Rousseau, Althusser was also talking to himself as a reading, forty years later, of the pages on the materialism of the encounter shows.

In these three lectures delivered in 1972, Althusser sets out to explicate a well-known text, Rousseaus Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men, a text elucidated many times before him. He proposes to analyse the less current aspects of the text, for, he says, the history of philosophy has left these aspects aside in drawing up its accounts or settling its accounts.

Rousseaus text

Rousseaus Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, as its title indicates, examines inequality, that is, political and social life, by setting out from the origin, that is, the period preceding the advent of society, in order to follow societys emergence and development with reference to this origin. This was a well-worn subject in the eighteenth century, in what was known as natural law philosophy or, again, the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Philosophers go back to the origin, before society, in the state of nature, and, on the basis of a discussion of this first state, they explain why society came into existence: since this state is not viable, since men kill each other in it (that is the state of war), they have to leave it by agreeing to abolish the freedom to do what one likes and by making laws and choosing leaders to enforce them (that is the social contract). Hobbes and Locke after him produced two different scenarios from this common stock, but this theoretical configuration (state of nature/state of war/social contract) forms the absolute horizon of Enlightenment thought: every philosopher, including Rousseau, thinks within this model. Many In his course, Althusser proposes to bring out the radical originality of Rousseau, who thought in the philosophy of the Enlightenment and against this philosophy, on the basis of a completely unprecedented philosophical dispositive. We shall see that Althusser does not study the usual Rousseauesque questions (natural law, original goodness, the critique of different forms of despotism, and so on), but directs his attention to less concrete aspects of Rousseaus thought.

Before approaching Althussers lesson, let us take a look at the way Rousseaus Discourse on the Origin of Inequality presents itself. This text often called the second Discourse because it was preceded by the Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts has two parts. The first runs from the origin to the eve of society; the second treats the establishment of society beginning with the emergence of property. (The true founder of civil society was the first man who thought of saying, This is mine. Its descriptive style and simple diction have given rise to the idea of a visionary, utopian, romantic Rousseau, and it is classified more often as literature than as philosophy in school and college curricula.

The second part of the Discourse explains that this state of infancy could well have gone on forever, but that natural catastrophes, accidents, modified this first life, which became impossible (because of climatic change, the increasing scarcity of foodstuffs, and so on). Men were forced to gather in groups (families, villages, huts) and they forged connections with each other (to hunt big game, for example). This new life engendered new feelings: self-esteem (how others see me), imagination, reason. This second epoch, which Rousseau calls the youth of the world, is a first step beyond nature, a step, but just a step, and it would have been however, opened the third period: thanks to some chance occurrence (perhaps the eruption of a volcano), men discovered metallurgy, and the domestication of fire enabled them to clear land and invent agriculture; this led to a sort of system of economic exchange (a division of labour between metallurgists and farmers), a system that lasted as long as there was still land to be cleared.