Table of Contents

Preface

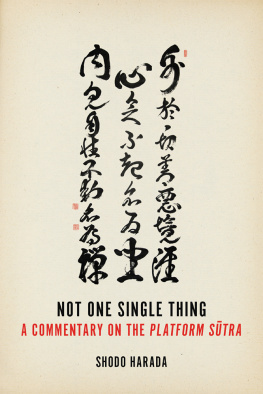

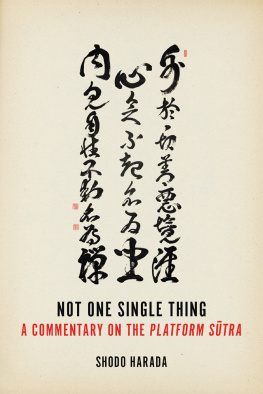

References to the moon appear frequently in Zen koans as a shorthand for the awakened mind. Although these calligraphy phrases are not the moon itself, they offer a means for awakening to the minds wisdom by serving as a reminder of the teachings when a teacher is not present. The calligraphies themselves provide an expression of the awakened mind, a visual Dharma, capturing the living energy of a moment in ink on paper. Thus, words and images work together to convey the essence of Zen to the viewer and reader.

Known internationally as a calligrapher and master teacher, Shodo Harada was born in 1940 in Nara, Japan. He began his Zen training in 1962 when he entered Shofuku-ji monastery in Kobe, Japan. After training under Yamada Mumon Roshi (19001988) for twenty years, he received Dharma transmission and was appointed abbot of Sogen-ji monastery in Okayama, Japan, where he has taught since 1982.

Harada Roshi is heir to the teachings of Rinzai Zen Buddhism as passed down in Japan through Master Hakuin and his successors. Harada Roshis teaching includes traditional Rinzai practices informed by deep compassion and permeated by the simple and direct Mahayana doctrine that all beings are endowed with the clear, pure Original Buddha Mind. Proceeding from this all-embracing view, Harada Roshi has welcomed serious students (women and men, lay and ordained) from all over the world to train at Sogen-ji and the temples he has established near Seattle, Washington, and in Germany, as well as at more than a dozen sitting groups around the world.

This book began as a series of hand-bound gift books from Shodo Harada to his students. Each calligraphy was individually inked on a sheet of paper around five feet in length. They were then photographed by Alan Gensho Florence and Sabine ShoE Huskamp and prepared for printing by Alan Gensho Florence. The text to accompany each calligraphy was translated by Priscilla Daichi Storandt and then edited for the hand-bound books and reedited for inclusion here. For this book, Thomas Yh Kirchner and Mitra Bishop reviewed the text and offered much appreciated suggestions and corrections.

Tim Jundo Williams | Jane Shotaku Lago

Hana wa hiraku bankoku no haru

A single flower blooms and throughout the world its spring

In Zen, the word flower often refers to the Buddha, who is said to have been born under flowers, to have become enlightened under flowers, to have transmitted the Dharma with a flower, and to have passed away under flowers.

When the Buddha was enlightened under the bodhi tree, he saw the morning star and exclaimed, How wondrous! How wondrous! All beings from the origin are endowed with this same bright clear Mind to which I have just awakened! For forty-nine years the Buddha taught that each and every person has the possibility of awakening and that this opportunity to awaken is the deepest value of being alive.

One day on Vulture Peak, instead of lecturing as usual, he silently held out a single flower, and Makakash Sonja smiled spontaneously. With this the transmission of the Dharma began.

The Buddha knew that his awakening was the awakening of all people and that no fame or fortune or any possession or knowledge brings a joy as great as the joy of awakening to our deepest Mind. We too can be born and can die under flowers, can finish this life as the Buddha did.

When a single flower blooms, it is spring throughout the world.

Shunshoku ni kge naku

Kashi onozukara tanch

In spring colors there is no high nor low

Some flowering branches are by nature long, some short

In spring, the ice melts and the severe chill of winter loosens its grip. In the warm sunlight, blossoms appearplum, peach, apricot, and many others. Everywhere, signs of spring are evident. The insects start to fly, seeking the sweetness of the flowers, and the birds sing. Everything that has endured the hard winter all at once expresses the great joy of this season.

This is the Way of Great Nature, the sutra that embraces all and through which we receive everything. Yet each of us carries a multitude of memories and knowledge, dualistic perceptions and strivings that influence our outward perception and distort our view of Nature. We can describe and attempt to explain this Great Nature, but to receive it directly and without hindrances is difficult.

When we let go of extraneous thoughts and see each thing exactly as is, with no stain of mental understanding and dualism, everything we see is true and new and beautiful. For those who have awakened to this Truth, whatever they encounter is the Buddhadharma, just as it is. No matter what is encountered, there is nothing that is not the Truth. When we look at something and dont recognize it as the Truth, that is not the fault of the thing we are seeing; it is because our vision is obscured by explanations and discursive thoughts.

Doing zazen, we let go of all extra thinking and perceive with a simple, direct awareness. There is no longer any separation between the person who is seeing and what is being seen. No explanations or ideas about what is being seen are necessary. Not holding on to any preconceived idea, we match perfectly with what we see, and there the Truth and the world are brought forth spontaneously. If we have no subjective opinions or preconceived notions, no small-minded I remains. There is only oneness. Anything we see and hear is Truth. There is nothing that is not the Buddha.

From the origin we have a mind like a clear mirror. To know this mind directly and completely is satori. That empty mirror gives rise to many associations as it encounters the outside world. When we become that emptiness completely, the world is born forth, clear and empty. Then, whatever we encounter, we become it completely and directly. This is the subtle flavor of zazen and is the mind of Buddha and of God.

When we see things from this mind, we see that the southern branch of the tree is longer than the northern branch, although the same warmth of spring touches both. Long is not absolute, and short is not lacking in anything. We need to see everything in society in that way as well. When we are with an elderly person we become that elderly person and can say, Yes, it must be so lonely, so hard. When a child comes, we are able naturally to sing and play with the child in the childs way. We see a pine and become a pine; we see a flower and become a flower. This is our simple, plain, natural mind. From there we have the purest way of seeing, and this is where the Buddhadharma lives.