Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2020 by Merewether LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Convergent Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

C ONVERGENT B OOKS is a registered trademark and its C colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Scripture quotations marked ESV are taken from the Holy Bible, English Standard Version, ESV Text Edition (2016), copyright 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked NIV are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Scripture quotations marked NKJV are taken from the New King James Version. Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked NRSV are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked RSV are taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1952, [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Illustration credits appear on .

Hardback ISBN 9780593236666

Ebook ISBN 9780593236673

convergentbooks.com

Book design by Carole Lowenstein, adapted for ebook

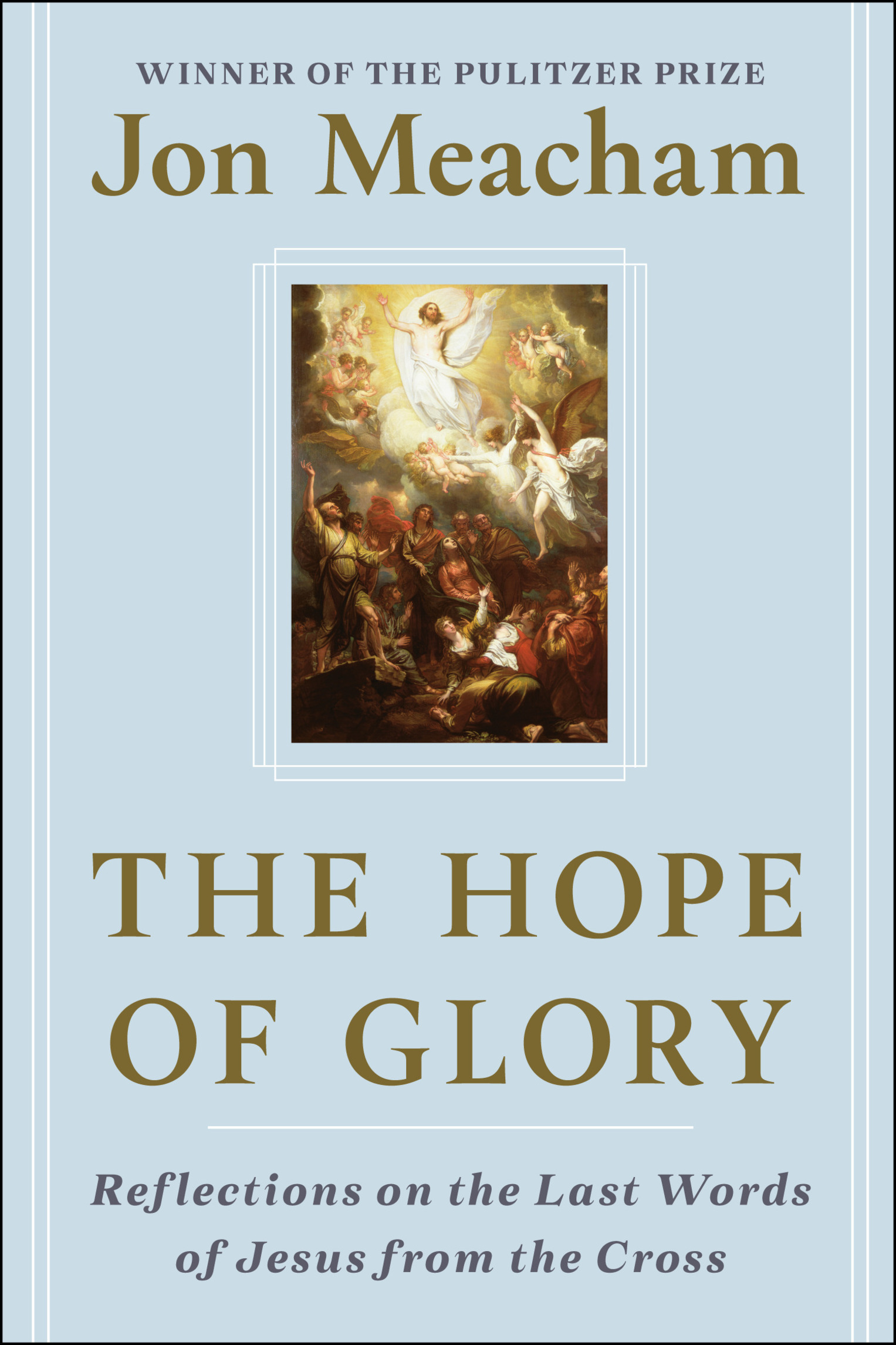

Cover design: Jessie Sayward Bright

Cover image: The Ascension by Benjamin West, photo Rafael Valls Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images

v5.4

ep

CONTENTS

For now we see through a glass, darkly, but then face to face.

T HE F IRST E PISTLE OF P AUL TO THE C ORINTHIANS

It is far better to accept teachings with reason and wisdom than with mere faith.

O RIGEN OF A LEXANDRIA

PROLOGUE

In the Beginning

But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness.God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty.

T HE F IRST E PISTLE OF P AUL TO THE C ORINTHIANS

In the world ye shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world.

J ESUS OF N AZARETH, THE G OSPEL OF J OHN

I T WAS ONLY A BRIEF MOMENT, a small, seemingly throwaway remark in the midst of the most significant interview in history. In the Gospel of John, Jesus of Nazareth has been arrested and brought before Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. So you are a king? Pilate asks, and Jesus says: You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Every one who is of the truth hears my voice. Then, in what I imagine to be a cynical, world-weary tone, Pilate replies: What is truth?

What, indeed? Jesus says nothing in response, and Pilates question is left hangingan open query in the middle of Johns rendering of the Passion. The search for an answer unfolds even now, for the hunger for truthabout the visible and the invisible, the seen and the unseen, the hoped-for and the fearedis among the most fundamental of appetites.

And that perennial quest for a reply to Pilate tends to take religious form. All men need the gods, Homer wrote, and nothing since antiquitynot the Scientific Revolution, not the Enlightenment, not Darwin, not anythinghas altered the impulse of human beings to organize stories and create systems of belief that draw on the past, give shape to the present, and promise a future of justice, mercy, and peace. Gods, the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich wrote in the middle of the twentieth century, are beings who transcend the realm of ordinary experience in power and meaning, with whom men have relations which surpass ordinary relations in intensity and significance.

For Christians, the central truth of existenceour ultimate concern, in a phrase of Tillichsis captured in the death and resurrection of Jesus. Without Good Friday, there is no Easter; without Easter, there is no deliverance from evil; without deliverance from evil, there is no victory of light over dark, of love over hate, of life over death.

Yet that victory is the radical, revolutionary, and essential promise of Christianitya promise revealed to us in the Passion of Jesus. The work of discerningor, depending on your point of view, assigningmeaning to Good Friday and to the story of the empty tomb is a historical as well as a theological process, as was the construction of the faith that has shaped, and is shaping, the lives of billions of believers.

I am one among that innumerable company, and this book is a series of reflections on the Last Words of Jesus from the crosswords spoken on a Friday afternoon that is at once impossibly remote and yet imaginatively close to hand. It is a devotional work, not a scholarly one. I am an Episcopalian who was raised and educated in the faith, and I would be disheartened if my own young children were to turn away from the church in which they have grown up. I am, however, in no sense an evangelical, for I do not share the view that faith in Jesus is the only route to salvation, nor am I determined to convert others to my point of view. It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god, Thomas Jefferson remarked. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg. In a sermon, John Lelanda leading Baptist preacher in Virginia and Massachusetts in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuriesonce observed, Experience teaches us that men who are equally wise and good may differ in political as well as in theological or mathematical opinions. Some fourteen hundred years earlier, in the fourth century, the Roman writer Symmachus, arguing against Christians who wanted to remove an altar to the pagan deity Victory, said, We cannot attain to so great a mystery by one way. I agree.

So what do I believe? I adhere to the broad outlines of the Christian faith as it has come down through the Anglican tradition. I profess the creeds, I confess my (many) sins, I make my communion, I say my prayers. And I believe that in so doing I am taking part in a drama whose ultimate purposes I cannot yetand may neverfully grasp but in which I invest my hopes that someday, in some way, all things will be made new.

An important note: Though this book began as a series of sermonswhich are, by definition, discourses on religious subjectsit is about illumination, not conversion. I am sharing these meditations in the hope that a sense of history and an appreciation of theology might help readers make more sense of the cross in a world too much given to the competing forces of hostile skepticism, blind acceptance, or remote indifference. In the Hebrew Bible, in the midst of great suffering, Job proclaims a great faith: I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth. If Job could