Arktos

London 2018

Copyright 2018 by Arktos Media Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means (whether electronic or mechanical), including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Originally published as Maschera e volto dello spiritualismo contemporaneo . Italy, 1971.

Arktos.com | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Gab.ai

ISBN

978-1-912079-34-6 (Paperback)

978-1-912079-33-9 (Hardback)

978-1-912079-32-2 (Ebook)

Translation

John Bruce Leonard

Editing

Martin Locker

Cover Design

Andreas Nilsson

Layout

Tor Westman

Translators Introduction

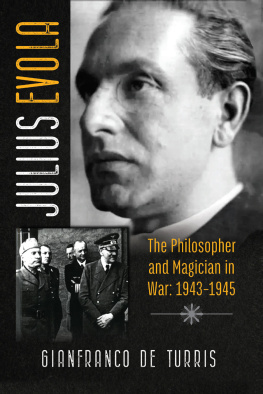

I n 1932, Julius Evola, still then a youngish man fast upon the brink of those ideas that would render him famous (or infamous) in time to come, published a book of ostensible critique on the variety of spiritualist forms, schools, cults and teachers which then was much in vogue in his society and in the wider West, entitled Maschera e volto dello spiritualismo contemporaneo . The book was destined to be quickly overshadowed (not to say eclipsed altogether) by his subsequent publication, just two years later, of Revolt Against the Modern World , and, despite being twice republished by Evola himself with certain suggestive alterations, was finally after his death to settle to the level of what are largely and rather passively considered Evolas secondary works. For us in the Anglophone world, the easiest index of this unofficial hierarchy is given by the order in which Evolas books have received translation; this reflects, not certainly the inherent worth of these books, but rather the importance which is more or less granted them by primarily Italian Evolian criticism today. It is then not particularly inspiring to realize that the present work has been one of the last of all Evolas works to find its way into English.

Yet what we have just said bears emphasis: the assumption that a given Evolian work is secondary often enough reflects less the quality of the book itself, than the miscomprehensions of its readers and critiques, owing in many cases to the nature of the time in which we live and the suspicion and carelessness which has attended to Evolas name (whenever it has been considered) almost since the end of the War. Even more glaring examples could be given of such misunderstandings, but we limit ourselves to consideration of the present book. Mask and Face of Contemporary Spiritualism has been relegated to the lesser works of the Evolian oeuvre, we may suppose, for two principal reasons: first, it was originally published as a compilation of previously published essays, rather than as an independent and original whole; second, it treats of specific historical phenomena, and thus might appear outdated. Before we set out to uncover points of reference for approaching the book itself, it would be opportune to dispel both of these motives for that underestimation which the present work has so unjustly suffered.

As to the first notion, that Mask and Face (as indeed several of Evolas works) was originally a compilation of essays rather than an independent and original work, the implication being that it therefore deserves less consideration than a book written all at once and at a go, as it wereI have argued before (in my introductions to Recognitions and The Bow and the Club ) that the mere fact that these books employ already published material hardly entitles us to take these works as mere compendia, of a level with, for instance, the great many posthumous volumes of Evolas essays. These latter works have value in the pieces ; but any work organized by Evola himself has value as a whole . To speak of no other concerns, the mere assembly of these essays demanded of Evola a certain discrimination and planning, unless we are to suppose that he went about their selection and ordering altogether haphazardly, on a whim, taking names at random and piling them one on top of another, just soa notion which mocks itself in its very utterance, so ludicrous is it. The very act of choosing these essays, and not others, of placing them in this order, and not another, suggests that the book as a whole must be conferred a higher dignity than some miscellaneous arbitrary of shorter writings.

This to say nothing of the fact that Evola never merely compiled essays, leaving the matter at that. The books that he formed of previously published material always included emendations, expansions, reworkings of the material in question, at Evolas own hand; this fact forces us to consider the changes in question and to evaluate themwhich is equivalent to saying that we must take these works as independent works, and not as echo-filled repetitions or representations of prior statements.

What we have said so far, despite the logic in it, might appear to have a flavor of mere supposition. Fortunately, we are not constrained to leave the matter at mere hypothesizing; we have definite biographical knowledge which comes to our aid here, to demonstrate the validity of what we have asserted. Mask and Face was not published just once, in 1932, but three separate times, once again in 1949, and yet again toward the end of Evolas life in 1971, just three years before Evolas demise. This fact alone attests to the importance which Evola ascribed to this book; but there is more. The first publication, though it did indeed employ prior essays, included also some totally new material, as the chapter on Catholicism. Both reprintings, too, came with additional material, original chapters which were added in each case, including a second conclusion. Nor can these merely be taken as bringing the book up to date with the newest follies in the world of neo-spiritualism, since the first major change in 1949 came with the addition of a key chapter on Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, both of whom had been dead for about half a century or more. In 1972, on the other hand, Evola added the chapter on Satanism, which, in the figures of Anton LaVey and the brief mention made of Charles Manson, certainly represented mere recent developments; less so, however, that of Aleister Crowley, who had already ascended to some higher plane twenty-five years before the third publication of this book. More: the additional material was not merely tacked on to the end of the book, as an afterthought, in final chapters or in appendices, as one would expect had the book itself been merely pasted together just so. The new chapters were rather interposed each time between the last and the penultimate. All of this attests to a unified, overarching, clear-sighted structure which Evola had in mind for this book, and one which absolutely nullifies the thesis that this book can be taken a priori as a work of secondary or marginal importance merely on account of its material.

But what of that other chargenamely, that this book treats of a subject matter which has grown stale, speaking as it does of currents, movements, schools, etc. which are no longer much in fashion among the spiritual seekers of our time? Or, to phrase this argument otherwise: what was contemporary at the publication of this book on contemporary spiritualism, is no longer contemporary to us; we are living a fundamentally different circumstance, and the trends and dangers for us have altered, so that Evolas treatment, while it might be interesting from the standpoint of, say, historical studies, cannot have a great deal of relevance for us today. Why then should we read this book at all, supposing that particular historical investigation does not interest us?