CALMING THE MIND

Tibetan Buddhist Teachings on

Cultivating Meditative Quiescence

CALMING THE MIND

Tibetan Buddhist Teachings on

Cultivating Meditative Quiescence

by Gen Lamrimpa (Ven. Jampal Tenzin)

Translated by B. Alan Wallace Edited by Hart Sprager

Contents

15

Unsuitable Motivations

Meaningful Motivations

Rebirth in the Form or Formless Realms

Liberation or Nirvana

Full Awakening

26

The Seven-Limb Puja

Building a Strong Foundation

Patience

Physical and Mental Obstacles

Potential Problems

Questions and Answers

41

Dwelling in a Favorable Environment

Reducing Desires and Developing Contentment

Rejecting a Multitude of Activities

Maintaining Pure Moral Discipline

Rejecting Thoughts of Desire for Sensual Objects

46

Preparation

The Actual Practice

Posture and Other Physical AspectsCounting the Breath

Questions and Answers

55

The First Fault: Laziness

Four Antidotes to Laziness

PliancyEnthusiasmAspirationFaith

The Interaction of the Four Antidotes

The Excellent Qualities of gamatha

Questions and Answers

64 67

Ascertaining the Specific Object of Meditation

The Second Fault: Forgetfulness

Establishing the Faultless Approach

Non-Discursive StabilityStrength of Clarity

The Third Fault: Laxity and Excitement

Maintaining Awareness of the Object

Antidotes to Laxity and Excitement

Dispelling a Faulty Approach

Duration of Sessions

Understanding That Arises from Reflection

Questions and Answers

86 89

The Practice When Either Laxity or Excitement Arises

The Definition of LaxityThe Definition of Excitement

Cultivating Vigilance That Recognizes Laxity and Excitement

The Fourth Fault: Non-Application

Antidotes for Non-Application

Definition of Intention

Additional Remedies for Laxity

Additional Remedies for Excitement

Recognizing the Causes of Laxity and Excitement

The Fifth Fault: Application

The Antidote for Application

Summary of the Five Faults and Eight Antidotes

Questions and Answers

113 115

The Nine Mental States

Differences Between the Nine Mental States

Questions and Answers

124 127

Accomplishing the Six Mental Powers

The Four Forms of Attention

133

The First and Last Antidote

Signs of Pliancy

Questions and Answers

138

Editor's Note

On January 6, 1988, at Cloud Mountain Retreat Center in Castle Rock, Washington, a group of twenty-four American dharma students and aspiring meditators began a gamatha retreat under the guiding hand of the Tibetan lama Gen Lamrimpa (the Venerable Jampal Tenzin). Some of us had made a three-month commitment to the practice, others of us were there for six months, and eight of us had committed ourselves to a year of meditation.

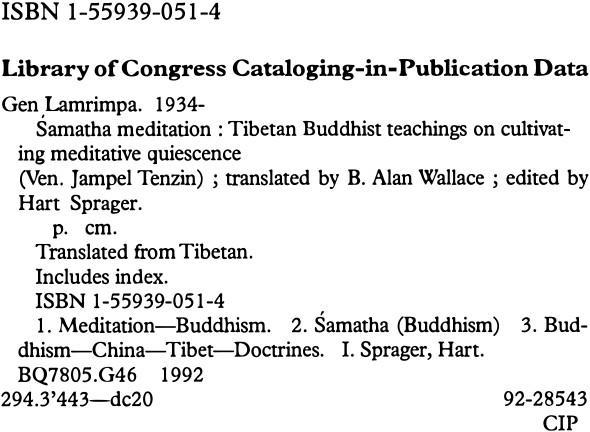

The body of this work is made up of the teachings on samatha Gen Lamrimpa gave during the first two weeks of the retreat. Those teachings were based on The Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path of Awakening by Tsong-kha-pa, who in turn based his teachings largely on Maitreya's text Examination of the Center and the Extremes.

Gen Lamrimpa included teachings by Asanga, namely his text called The Stages of the Listeners and the teachings of Santaraksita on The Essence of the Center. In addition he included teachings by Kamala ila-The States of Meditation, as well as the Compendium of Practices.

All of these teachers, as well as Santideva (whom Gen Lamrimpa quotes many times during the teachings), had perfectly attained gamatha during their lifetimes. At the time the teach ings were given, Gen Lamrimpa himself had twenty years' experience in gamatha and other meditative practices.

Transferring a teacher's words to paper is a relatively simple process but anyone who has experienced them must realize that the task of transferring to the printed page the vibrance and vitality present in the oral transmissions of a true master is next to impossible. Recognizing the impossibilities inherent in the task, all of us who have worked on this book have been motivated by the wish to pass on the essence of the teachings as well as the fundamentally unique quality of Gen Lamrimpa's presentation.

Throughout the teachings, Gen Lamrimpa began the day by speaking about motivation and the ways in which we, his students, could use the proper motivation to enhance our own internal processing of what we were about to hear. While what he said invariably enhanced our motivation, it sometimes seemed to have less than a direct relationship to the subject of gamatha. In that motivation is such an essential aspect of the practice, there was simply no way or reason to exclude those motivational moments from this edition. Four chapters-six, eight, ten and twelve-have been compiled from these daily teachings.

In his teachings, Gen Lamrimpa demonstrated his ability to present technical and often complicated material in a very uncomplicated and down-to-earth manner, and one of Alan Wallace's most outstanding qualities as a translator is his ability to transform that down-to-earth presentation into truly vernacular English while at the same time retaining the precision of the terminology and exactitude of the concepts being presented. It is my hope that the delicate balance they were able to create is evident in this rendering.

Finally, Gen Lamrimpa constantly emphasized the importance of continuity. At the same time, he took the liberty to digress from the formal outline of the presentation whenever such a digression enhanced the understanding of his students. Those digressions, which turned out to be shortcuts to the very heart of the matter, are included here just as they came up in the teachings.

It may be helpful for the reader to know a little about the basic daily routine we followed during the retreat. It was very much of an accordion-style schedule, devised so that each of us could function as much as possible on our own time clock. We awoke at five a.m. and went to sleep at around ten p.m. Except for hour-and-a-half breaks for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and short tea breaks throughout the day, we were urged to devote every waking minute to the practice. We were encouraged to maintain silence in all group areas, such as the dining hall, and to avoid contact with one another. We meditated individually in our own rooms. We started meditating in fifteen-minute sessions and took a fifteen-minute break between sessions, plus an occasional longer tea break as it seemed necessary. This format allowed for as many as eighteen quarterhour sessions throughout the day at the beginning of the retreat, a total of four and a half hours of actual meditation in what would ideally be a full day of practice.

As our proficiency in the practice increased, we extended the length of the sessions but held firm on the length of the break. At the end of a year of practice, some meditators were doing sessions that extended well beyond two hours. Thus, the time of formal meditation increased from the base four and a half hours to somewhere between six and twelve hours per day, depending on the individual's progress.

Next page