THE FIRST DALAI LAMA

Translated, edited, and introduced by

Glenn H. Mullin

vii

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 67

CHAPTER 83

CHAPTER 175

CHAPTER 201

CHAPTER 253

CHAPTER 289

CHAPTER 317

CHAPTER 333

VER THE PAST TWO DECADES I have published almost a dozen books with Snow Lion on the lives and works of the early Dalai Lamas. As most readers will know, the present Dalai Lama, who was born in 1935, is the fourteenth in this line of illustrious reincarnations.

VER THE PAST TWO DECADES I have published almost a dozen books with Snow Lion on the lives and works of the early Dalai Lamas. As most readers will know, the present Dalai Lama, who was born in 1935, is the fourteenth in this line of illustrious reincarnations.

When I first started this project, almost nothing was known in the West about these extraordinary men. Coverage of them had been limited to a paragraph or two, or a page or two at best, in academic books on Tibetan cultural and political history. Even though many of these incarnations had written dozens of works on Buddhist philosophy, meditation, mysticism, and other enlightenment-related topics, and had also written hundreds of songs and poems, no significant text by any of them had ever been translated into English.

With each of these books I usually incorporated a traditional biography and a selection of their most accessible writings. Usually the selection would be on diverse subjects, in an attempt to convey the range and depth of these Buddhist teachers, from mystical poems to works on philosophy and tantric practice.

Most of these titles have been out of print for over a decade now. Sidney Piburn, my editor at Snow Lion, thought that it would be useful to bring out an anthology of some of the tantric works that I had used in that series. Tantric Buddhism is becoming better known in the West these days, but there is still a paucity of authentic translations from classical sources. The great popularity achieved by the early Dalai Lamas was due in part to the clarity and power of their tantric writings, so Sid's suggestion did not seem unreasonable. This volume is the result.

On the technical side, I have tried to keep footnotes to a bare minimum so as to allow the reader to enjoy the mood of the originals, rather than create the distraction of a constant barrage of "whispered asides." Moreover, I have also presented any Sanskrit and Tibetan terms that are used in a simplified "phonetic style" for ease in reading. For example, "Khedrup" looks far more palatable to me than does "mKhas-grub," and "Lobzang" seems more accessible than "bLo- bzang." Scholars should be able to easily reconstruct the more formal spellings if they wish to do so, whereas these formal spellings are irrelevant to the general enthusiast.

With Tibetan text titles, however, a system of easy phonetics would be inadequate. Therefore here I have used the formal system of transliteration.

Most Dalai Lamas wrote extensively on Tantric Buddhism. The material chosen for this anthology is intended as a mere sampling of their contribution, with the intent to give the reader a sense of the authentic tradition.

Glenn H. Mullin Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, March 7,20o6

THE LEGACY FROM BUDDHA SHAKYAMUNI

UDDHA TRAVELED and taught widely for some forty-five years after his enlightenment, and his audiences were diverse. Even though India at the time was a highly literate society, nothing of what he said was written down during his lifetime. Instead, various individuals were entrusted with memorizing the gist of each discourse. The work of transcribing his words took place only with the passage of generations.

UDDHA TRAVELED and taught widely for some forty-five years after his enlightenment, and his audiences were diverse. Even though India at the time was a highly literate society, nothing of what he said was written down during his lifetime. Instead, various individuals were entrusted with memorizing the gist of each discourse. The work of transcribing his words took place only with the passage of generations.

Tibetans believe that this reluctance on the part of the Buddha and his immediate followers to commit the enlightenment teachings to paper, and instead to preserve them as oral traditions, was a purposeful strategy gauged to maintain the maximum fluidity and living power of the enlightenment experience. It only became necessary to write things down when the darkness of the changing times threatened the very survival of the legacy. An oral tradition becomes lost to history should its holders pass away without first passing on their lineages.

This intended fluidity, and the according safeguard against the establishment of an "enlightenment dogma," is perhaps best demonstrated by a verse that the Buddha himself said shortly before his death:

Do not accept any of my words on faith, Believing them just because I said them.Be like an analyst buying gold, who cuts, burns, And critically examines his product for authenticity. Only accept what passes the test By proving useful and beneficial in your life.

This simple statement empowered future generations of Buddhist teachers to accept and reject at will anything said by Buddha himself as well by his early disciples. If something that was said by them did not pass the test of personal analysis, one could simply discard it as being limited in application to particular times, people, or situations, and therefore as only contextually valid.

1. BUDDHA'S LEGACY OF EXOTERIC AND ESOTERIC TRANSMISSIONS

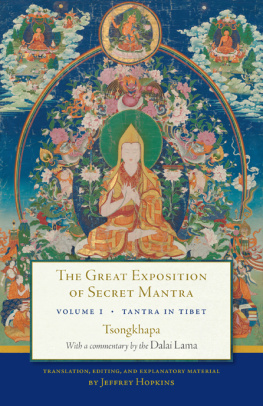

In his A Brief Guide to the Buddhist Tantras (translated in Chapter One of this volume) the Thirteenth Dalai Lama quotes two verses from the writings of the incomparable Lama Tsongkhapa:

There are two Mahayana vehicles For traveling to complete buddhahood: The Prajnaparamitayana and the profound Vajrayana. Of these, the latter greatly surpasses the former. This is as well known as the sun and moon.There are many people who know this fact And pretend to carry the tradition of the sages, Yet who don't search for the nature of the profound Vajrayana. If they are wise, who is foolish? To meet with this rare and peerless legacy And yet still to ignore it: How absolutely astounding!

Next page

VER THE PAST TWO DECADES I have published almost a dozen books with Snow Lion on the lives and works of the early Dalai Lamas. As most readers will know, the present Dalai Lama, who was born in 1935, is the fourteenth in this line of illustrious reincarnations.

VER THE PAST TWO DECADES I have published almost a dozen books with Snow Lion on the lives and works of the early Dalai Lamas. As most readers will know, the present Dalai Lama, who was born in 1935, is the fourteenth in this line of illustrious reincarnations.

UDDHA TRAVELED and taught widely for some forty-five years after his enlightenment, and his audiences were diverse. Even though India at the time was a highly literate society, nothing of what he said was written down during his lifetime. Instead, various individuals were entrusted with memorizing the gist of each discourse. The work of transcribing his words took place only with the passage of generations.

UDDHA TRAVELED and taught widely for some forty-five years after his enlightenment, and his audiences were diverse. Even though India at the time was a highly literate society, nothing of what he said was written down during his lifetime. Instead, various individuals were entrusted with memorizing the gist of each discourse. The work of transcribing his words took place only with the passage of generations.