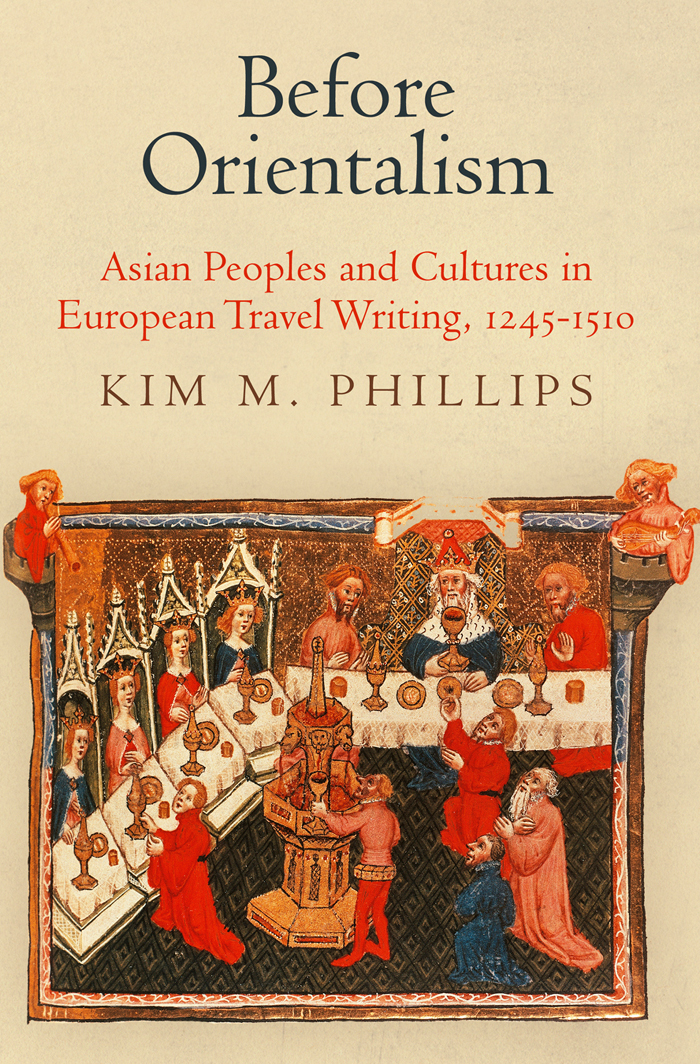

Phillips Kim M. - Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510

Here you can read online Phillips Kim M. - Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pennsylvania Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Phillips Kim M.: author's other books

Who wrote Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Before Orientalism

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

Before Orientalism

Asian Peoples and Cultures

in European Travel Writing, 12451510

Kim M. Phillips

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2014 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for

purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book

may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phillips, Kim M.

Before Orientalism : Asian peoples and cultures in European travel writing, 12451510 / Kim M. Phillips. 1st ed.

p. cm. (The Middle Ages series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4548-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Travel, MedievalAsiaHistorySources. 2. Travelers writings, EuropeanHistory and criticism. 3. AsiaDescription and travelEarly works to 1800. 4. AsiaForeign public opinion, WesternHistory. I. Title. II. Series: Middle Ages series.

GT5240.P55 2014

303.48'209dc23

2013019443

For John, Heloise, and Sylvie

Contents

Note on the Text

All English-speaking authors in this field find themselves compromised by the problem of spelling proper nouns. As a broad guide, I generally follow the forms employed in John Block Friedman and Kristen Mossler Figg, eds., with Scott D. Westrem, associate editor, and Gregory G. Guzman, collaborating editor, Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland, 2000). Chinese places and names are given in Pinyin without tone marks. Where there is potential for confusion, especially with regard to place-names, the medieval authors spelling is included as well as a currently accepted form. No doubt some readers will be dissatisfied with the results, but I hope that all will be able to recognize the people and locations mentioned or find them in a reference work or map.

When using abbreviated forms of medieval European authors names I include only the most distinctive part of the name (usually Anglicized). Christian names are generally preferred over bynames, but not surnames, except where the Christian name is too common to avert confusion: thus: Carpini rather than John, Rubruck rather than William, but Ricold and Jordan rather than Monte Croce and Catala. When an author is infrequently referred to or no part of his name is memorable, the whole is preferred (for example, Benedict the Pole, Andrew of Perugia).

In the text, quotes are generally given in English translation. The translations have been compared with the original text in the edition named in the endnotes and modified in some instances. To save space, the original Latin, French, Franco-Italian, or other wording is only briefly quoted, whether in the text or endnotes, when likely to be of special interest. References to the main primary texts in the endnotes are generally given by medieval author and now commonly used title, with book and chapter numbers or other subdivisions where available, followed in parenthesis to page references to the edition of the original language used and (in most cases) to an English translation. Where I have modified a translation or provided my own, this is made clear.

Introduction

I speak and speak, but the listener retains only the words he is expecting. The description of the world to which you lend a benevolent ear is one thing; the description that will go the rounds of the groups of stevedores and gondoliers on the street outside my house the day of my return is another; and yet another, that which I might dictate late in life, if I were taken prisoner by Genoese pirates and put in irons in the same cell with a writer of adventure stories. It is not the voice that commands the story: it is the ear.

To write a book is to make a journey. Yet as is so often the case with travel, the final destination may look quite different from what was initially imagined. In the early stages of research for this book, influenced by some recent studies on travel writing, I thought the distant parts of Asia might represent a location of definitive Otherness for late medieval European writers and readers. However, I have since moved far from that view, having found that the end location has a much more varied landscape than first envisaged.

This book examines European travel writing on central, east, south, and southeast Asia composed or in circulation from around 1245 to around 1510. Orient, Asia, far East (with lowercase f), distant East, and farther East will be employed as synonyms encompassing the whole area under discussion with due acknowledgment of the difficulties of these labels. Terms such as Orient and East have become problematic for modern commentators who rightly point to their geographic assumptions (East from where?), ideological baggage, and pejorative or romantic connotations. Yet to medieval Europeans the lands of Asia were literally in the distant East of their world. The book deals with descriptions of places we now call Mongolia, China, India, and Southeast Asia. It largely excludes the Holy Land and surrounding regions on the grounds that western Europes relations with middle eastern (and, indeed, northern African and southern Iberian) people were shaped by Christian rhetoric that sought to emphasize the religious basis of relations with, and alienation from, Islam and Judaism to a greater extent than discourse on cultures further east. Although Christian crusading rhetoric and anti-Judaic traditions had their own complexitiesindeed, were not univocally damningone cannot deny the persistence of later medieval Christian tendencies to condemn most stridently the religious and cultural traditions closest to its own. Geographical proximity and military threats may similarly raise tensions. As we will see, Europeans were most hostile in portrayals of Mongols in the early to mid-thirteenth century when the physical peril of Tartars was nearest.

This book does not tell the travelers stories of discovery again, apart from some necessary background material on authors, books, and audiences, nor is it a history of exploration and discovery. It does not treat the travelers narratives as sources of information on Asian cultures historians might use to supplement or support what they have learned from non-European sources. Rather, it attempts something different: a cultural history of aspects of the encounter between late medieval Latin Christians and Asian cultures with a focus on themes that have not usually been granted headline attention. In particular, it asks how prevailing European preoccupations with food and eating habits, gender roles, sexualities, civility, and the human body helped shape late medieval perspectives on eastern peoples and societies. It aims to contribute to European cultural history, not Asian history. Its central argument is for a distinctive European perspective on Asia during the era c. 1245c. 1510. Attitudes were moving away from tendencies to create a homogenous India of marvels and monsters yet were little touched by the colonialist mentalities that would emerge through the early modern era and dominate the modern. It argues that desire for information and for pleasure were two chief impulses guiding late medieval readers interest in travel writing on Asia. In regard to the first motivation, some authors supplied specific information to help with immediate military and evangelical necessities. Other travelers, particularly when writing on China, sought to satisfy a more generalized hunger for knowledge about civilized living that pervaded late medieval burgess and noble life. Readers appetites for pleasure were also variously satisfied. Some representations of eastern peoples fulfilled the urge to wonder, which has been noted as an important characteristic of medieval cultures, while other elements of their descriptions met desires for amusement or delight. Monstrosity or alien customs were comprehended within ancient conventions on the barbarian and could assist an emerging European sense of selfhood or in some cases provide a kind of pleasure through horror.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510»

Look at similar books to Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Before Orientalism: Asian Peoples and Cultures in European Travel Writing, 1245-1510 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.