ALEPH CLASSICS

THE TIRUKKURAL

The Indian subcontinents literary heritage is unparalleled. For thousands of years significant literary works have been created in many languagesSanskrit, Tamil, Prakrit, Pali, Urdu and Persian to name a few. Aleph Classics is committed to publishing new translations of the most significant of these works from time to time. These translations will be aimed squarely at the twenty-first- century readerthey will be distinguished by their readability, accessibility and scholarship. Aleph Classics will be elegantly laid out, designed and printed, and will carry on the companys tradition of publishing handsome, enduring books.

Books by Gopalkrishna Gandhi

FICTION

Refuge

NON-FICTION

Of a Certain Age: Twenty Life-Sketches

PLAYS

Dara Shukoh: A Play

TRANSLATIONS

Koi Achha Sa Ladka

(Translation of A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth into Hindustani)

BOOKS EDITED BY GOPALKRISHNA GANDHI

Gandhi and South Africa (with E. S. Reddy)

Gandhi and Sri Lanka

Nehru and Sri Lanka

India House, Colombo: Portrait of a Residence

Gandhi Is Gone: Who Will Guide Us Now?

A Frank Friendship: Gandhi and Bengal: A Descriptive Chronology

The Oxford India Gandhi: Essential Writings

My Dear Bapu: Correspondence between C. Rajagopalachari and

Mohandas K. Gandhi

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

First published in India in 2015 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright Gopalkrishna Gandhi 2015

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Aleph Book Company.

eISBN: 9789384067083

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

To the conflicted yet interwoven memories of

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari

(18781972)

and

Periyar E. V. Ramasami

(18791973)

Men of the light are men who care

Their words humane, hard messages bear

Tirukkural, Verse 91

CONTENTS

PREFACE

THE TIRUKKURAL

I

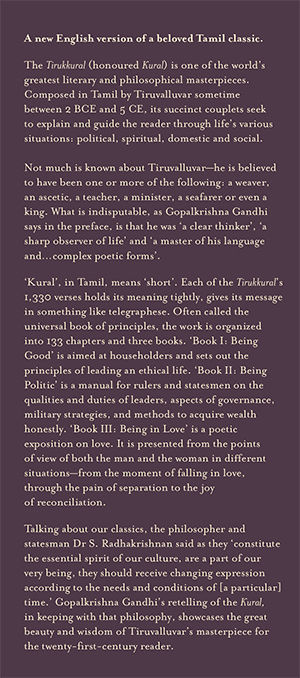

For the many who know the Tirukkural, this initial word about the book will be redundant. For those unfamiliar with Tiruvalluvars undimming work, a brief description of it might be useful.

Both the authors name and that of the work are given, that is, they are not original names, for we do not know what he was actually called, and he did not title his work.

Kural in Tamil means short. The 1,330 couplets that make up the Tirukkural are short, each making a compact, concise proposition. The first line, typically, has four words, the second has three. The syllables per line can sometimes vary, but not the number of words or metrical feet. Together, they are like a cluster of seven gems, set in two rows. The Tirukkuralthe honoured Kuralis traditionally dated to the immediate post-Sangam period, referring to the era of the Tamil academies (sangams) that are said to have flourished between 300 BCE and 300 CE. The Kural deploys the austerity of the Venba metrical form with its ellipses (tohai) to telling effect. Its author uses metrical feet (cir), alliteration (monai), second-letter alliteration (ethuhai) and rhythm (osai) like a master of cryptograms. Verbs are absent, nouns truant. This economy tightens the expression to that point beyond which tightening would strangle meaning. The opening couplet offers a perfect sample:

Akara mudala ezhutellam adi

Bhagavan mudatre ulahu

The first word of each line clicks into an internal rhyme + alliteration with the correspondence of sounds occurring without variation in the second letter before the rhythm flows into the third: A-kara/Bha-gava(n). Sanskrit has borrowed this as dvitakshara prasa (alliteration in the second letter). Containing, in the words of the books best-known translator, G. U. Pope, a complete and striking idea expressed in a refined metre, every one of the 1,330 kurals is believed to be the work of a single author, Tiruvalluvar. Written sometime between 2 BCE and 5 CE, the Tirukkural speaks within a frame, thinks without frontiers. It is presented in three Books. The first has traditionally been called the Book of Virtue, the second the Book of Wealth, the third the Book of Love. They deal with, respectively, righteous living, statecraft and conjugal love.

Tiruvalluvar was an exceptionally powerful thinker, a master of his language and its literatures complex poetic forms. He was a sharp observer of life. The Kural is the result of his literary labours, a spectacular insight into the workings of the human brain and the waywardness of the human heart. Admired as literature, venerated as secular gospel, translated times without number into the worlds different languages, the Tirukkurals teachings have yet been ignored by generation after generation of an unwise humanity.

II

When smitten by a book, readers want to become part of it, immerse themselves in the life of the volume they hold in their hands.

While the fever is on, they cannot part with the book. They keep it on their person, as W. B. Yeats did his copy of Tagores Gitanjali. I have carried the manuscript of these translations about with me for days, reading it in railway trains, or on the top of omnibuses and in restaurants, and I have often had to close it lest some stranger would see how much it moved me.

They of course talk about it as of a personal, even private, discovery to those close to them. Some of them, if they think of themselves as writers, will try to find a journal that might carry their review of it. The most ambitious, even audacious, way of finding a union with the workfor that is what the smitten wantis to try translating it and thereby enter the works very soul.

Translator ambition includes new translations in the same language and, in the case of fiction, screen versions and film scripts. Given in generosity, the permission is often regretted in hindsight. R. K. Narayan recounts how his novel, The Guide, when it was made into a film became another being. The location, he was told, need not be where he had visualized it to be. Malgudi will be where we place it, in Kashmir, Rajasthan, Bombay, Delhi, even Ceylon. When he protested that a tiger fight scene would be wrong, for there was no such thing in the story, he was assured that it was. He just gave up, in the spirit of the first line of a song in that film sung by Mohammed RafiKya se kya ho gaya! meaning What have you gone and done!

An author may dearly wish the go-ahead had not been given to a translator or to that mutilator calling himself transcreator, bemoan the translations excesses and lament its shortfalls, but once the deed is done, the translator becomes, for all time, part of the works aura.

Not all translations, of course, come about that way. Some are commissioned by the author or a publisher quite matter-of-factly for the benefit of readers belonging to another linguistic register. For the engaged translator such exercises can be no less fulfillingor self-fulfillingthan for the self-appointed one. This translation of Tiruvalluvars 1,330 rhymed Tamil aphorisms belongs to the latter category. It could very well make Valluvar exclaim from his post-earthly world: What have you gone and done!