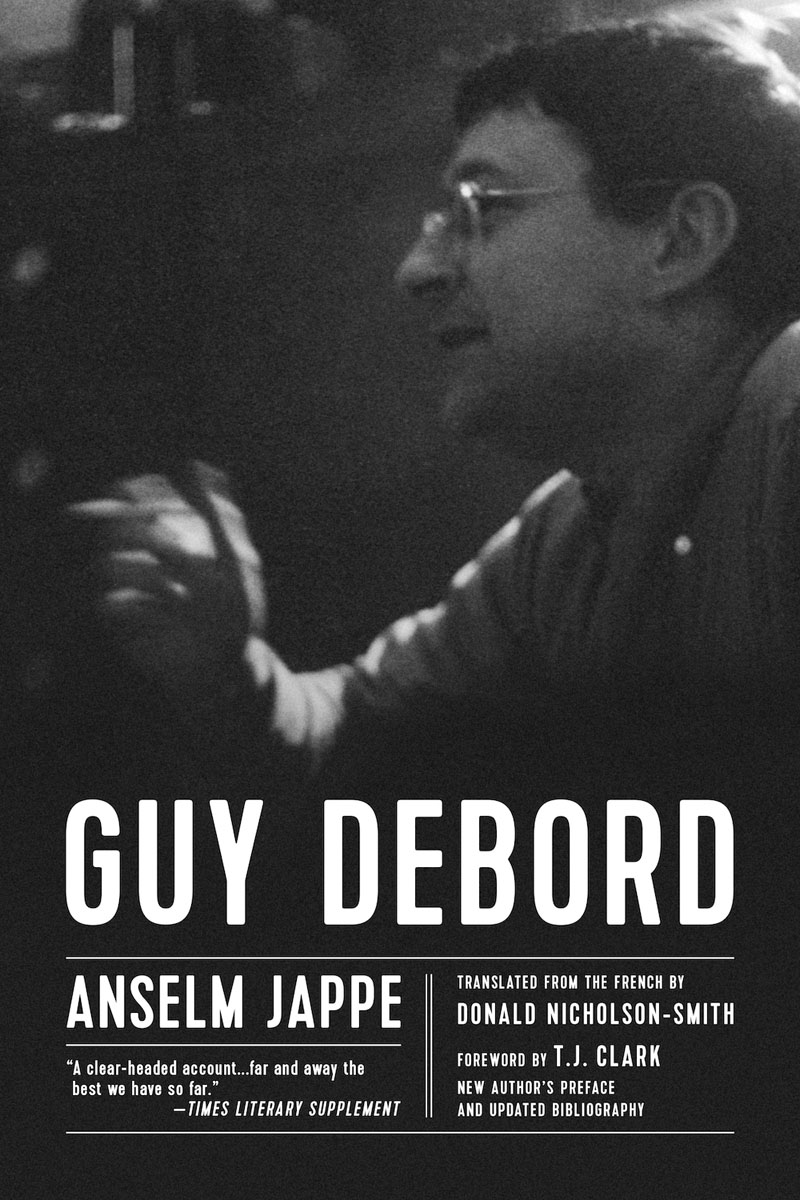

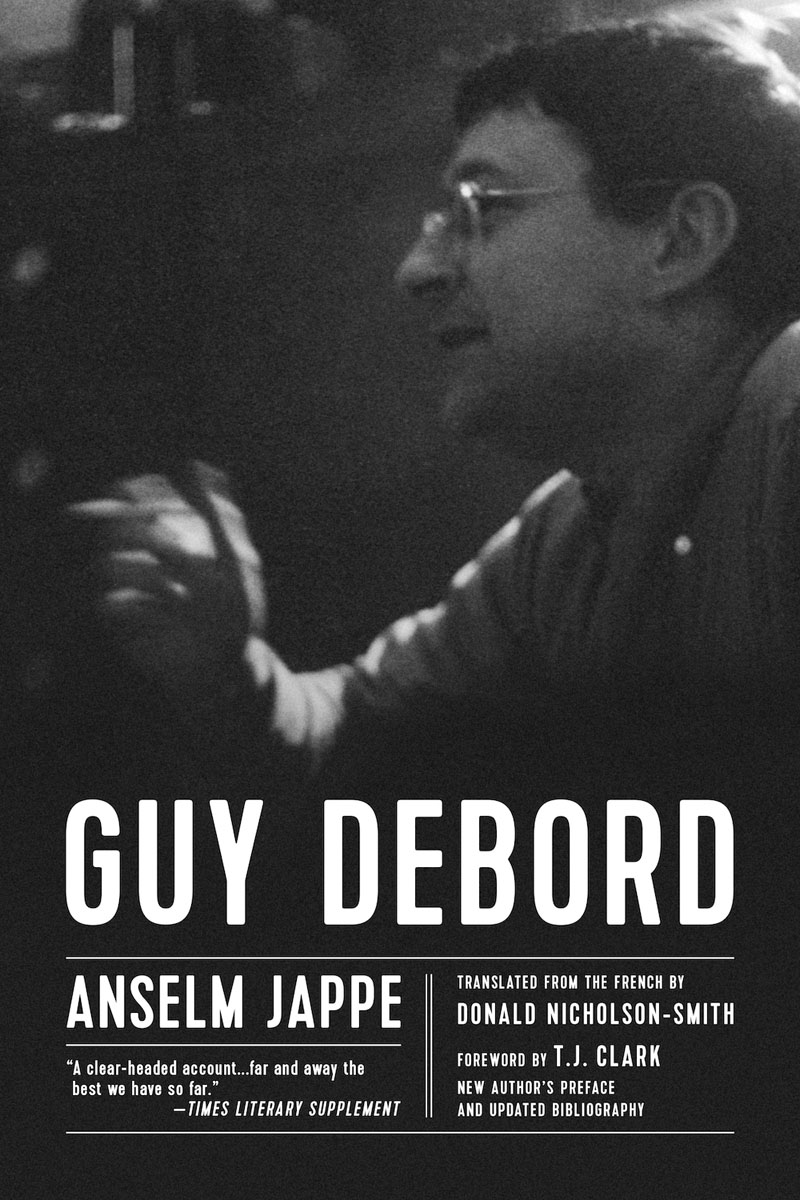

Praise for

Guy Debord

A clear-headed accountfar and away the best we have so far.

Times Literary Supplement

The only book on Debord in either French or English that can be unreservedly recommendedparticularly useful for its extensive treatment of the Marxian connection that is usually ignored in culture-oriented accounts of the Situationists.

Ken Knabb, editor of Situationist International Anthology

Jappe successfully gets to grips with the content of Debords and the SIs activity in a way that is accessible and doesnt require a vast amount of prior knowledge or an extensive vocabulary of obscure jargon in order to understand it. Debord has got a somewhat undeserved reputation for having an impenetrable and complex writing stylea myth which Jappe goes a long way towards refuting by examining the major concepts in The Society of the Spectacle and other works and putting them in the context of a wider historical view and in terms of the SI as a whole.

Do or Die

Guy Debord

2018 Anselm Jappe

Translation 2018 Donald Nicholson-Smith

Foreword 2018 T.J. Clark

This edition 2018 by PM Press

ISBN: 978-1-62963-449-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017942920

Cover by John Yates/stealworks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

Preface to the 2018 Edition

In his preface to the fourth Italian edition of The Society of the Spectacle, published in 1979, Guy Debord wrote that while most books of social theory were doomed to be forgotten after a short television debate, he foresaw quite another fate for his own book. He was undeniably right. The Society of the Spectacle, originally published in 1967, has become a classic and is one of the few books of revolutionary theory from the 1960s still widely read today.

After his death, Debords status passed from that of an underground hero, known only to a small elite which felt itself to be a kind of conspiracy, to that of a key figure of intellectual life. At the same time, he retained a subversive cachet, quoted variously by radical social theorists and activists, artists, and anybody wishing to appear critical towards the media. On the other hand, after a 2009 French ministerial decree declared his archives a national treasure (thus preventing their sale to Yale University, who were also eager to acquire them), they were purchased by the French National Library. For officialdom to proclaim a French author a national treasure so soon after his death is a rare accolade indeed. Some nevertheless considered this a betrayal, while others deemed it a just tribute to the importance of Debords work.

This kind of global fame has of course served as a cue for the production of a large number of writings and other works about Guy Debord in particular or the Situationist International in general. Originally published in Italian in 1993 during Debords lifetime and since translated into six languages, my book was the first monograph devoted to Debord rather than to the Situationists as a group. Following its publication, I was naturally most heartened to learn of Debords own appreciation of it. The availability of more and more source material since 199394 has meant that those aspects that were either absent from, or under-represented in my book have been open to full exploration by others in dozens of books and hundreds of articles. This new material includes a single-volume edition of collected works (2006) containing previously unpublished writings and annotations; eight volumes of Debords correspondence; DVD releases of his films and voice recordings; and the thousands of reading notes and other documents now in the French National Library collections. In addition, accounts of their own time with Debord have been provided by several of his associates and acquaintances in books and articles. Today it is even possible for researchers to check police files on Debord. By normal standards, therefore, this book ought by rights to be looked upon now as a mere forerunner, and largely outdated. If it is still readand now reprintedthis cannot be explained by the factual information it supplies, but solely by the way those facts are viewed.

The book does not dwell at any length on the history of the Situationist International and has even less to say about Debords personal life. It sought rather to determine Debords place in the history of revolutionary thought and praxis with particular reference to his ties with the past, the present, and also the future of Marxist or Marx-inspired ideas. I stressed the importance of this focus for me in my Afterword of 1999 to this English translation, but I make no claim to have dealt exhaustively with the issue. The fact is, however, that over the last two decades hardly anyone has seen fit to pick up on and develop the kind of interpretation of Debords work set out in these pages. As was already true in 1999, conventional readings of Debord have tended to concern themselves with his artistic side, especially his early promotion of psychogeography or dtournement, along with his critique of the media, co-opted versions of which have given us guerrilla media and fueled the digital media explosion. The emphasis of criticism in these spheres has thus been laid on media imagery rather than on the reality underpinning it. Some of the post-millennial studies of Debords filmsa flurry of interest in his archives, sources, work methods, and above all the relentless preoccupation with his private life, often with deplorable results from the standpoint of scholarshiphave all served to reinforce such readings to the detriment of more thoroughgoing investigations of his importance for the history of ideas. It is true that Debord refused to be considered a theorist of revolution, preferring to be called a strategist. But whereas the historical period where his strategies could have a direct impact on reality is fast receding into the past, what remains topical are his analyses of capitalist society as a society of spectacle, of spectacles function as a historical stage of commodity fetishism, and of its place within the broader historical context of the relationship between hierarchical societies and the use of time. There is of course nothing startlingly new in my claim that not enough attention has been paid to this, but it is a terrible shame that so little headway has been made down a path which, over and above theoretical considerations, can lead to Debords ideas retaining their subversive force rather than simply falling into the grasp of such magical rebranding as the one which has repackaged the Situationist concept of the drive as a smartphone app.

One might do worse, I wrote in my Afterword, than reiterate (in a slightly updated form) a sentiment first expressed in the Situationist journal in 1967: We want ideas to become dangerous once again. We cannot allow people to support us on the basis of a wishy-washy, fake eclecticism, along with the Derridas, the Lyotards, the Rortys and the Baudrillards (or, as in the original French, the Sartres, the Althussers, the Aragons and the Godards. Today, fifty years on, and twenty since the critical re-examination undertaken in my book, any hope of containing the misrepresentation and hijacking of even the Situationist legacy, which once seemed more resistant to such attacks than any other expression of revolutionary culture, is clearly a forlorn one. It is no longer a matter of defending this radical legacy against an army of recuperators, but of ensuring that in the midst of a torrent of nonsense, a discourse espousing a comparable radicalism may achieve currency.

Next page