To the One who is without end, is of ever-flowing wisdom, eternal, and whose abode is eternal To the One who is engrossed in the soul and the supreme teacher, the first Tirthankara Rishabha I offer my salutations To the One who was single-minded in penance and compassionate to his kith and kin. In his family was born Emperor Marichi Kumar who was reborn as the last Tirthankara Mahavira Those people are worthy of obeisance who strove to advocate human effort and purity of the soul In this line comes Acharya Bhikshumay his fame spread CONTENTS

To the One who is without end, is of ever-flowing wisdom, eternal, and whose abode is eternal To the One who is engrossed in the soul and the supreme teacher, the first Tirthankara Rishabha I offer my salutations To the One who was single-minded in penance and compassionate to his kith and kin. In his family was born Emperor Marichi Kumar who was reborn as the last Tirthankara Mahavira Those people are worthy of obeisance who strove to advocate human effort and purity of the soul In this line comes Acharya Bhikshumay his fame spread CONTENTS  The story of Rishabha is the story of the beginnings of Indian civilization. History rests on limiting shores; in the mystery of prehistoric times many universes lie hidden. On the foothills of the Himalayas, a civilization was being born. The Twin Age, or the primitive period, was coming to an end. From dwelling on trees, man was coming down to till the earth to make a living.

The story of Rishabha is the story of the beginnings of Indian civilization. History rests on limiting shores; in the mystery of prehistoric times many universes lie hidden. On the foothills of the Himalayas, a civilization was being born. The Twin Age, or the primitive period, was coming to an end. From dwelling on trees, man was coming down to till the earth to make a living.

At that time, in Chieftain Naabhis house, Rishabha was born. His birth heralded a completely new culture and tradition. His contributions to social organization were so significant that it later made Acharya Jinsen invoke him as the Creator, the one who Bestows, the Maker. This poem presents the life of Rishabha and so is titled Rishabhayan. The story of Rishabhas life is the biography of social organization. At the crossroads of two time periods the changes that take place in the geographic, social, mental and emotional states make for interesting understanding of the foundation of social development.

Development follows a certain order. Sometimes the order is transgressed and sometimes it is changed. When the order is broken, a leap is taken in progress and when there is a change, it results in a transition. This kind of transition is also called a revolution. It is revolution that transformed the inactivity in

The Age of the Twins into Karmayuga. It is revolution that organized wanderers into a kingdom as subjects of King Rishabha.

A healthy society is one in which there is no shortage of wealth and material and yet their influence on people is also not overbearing. In the Age of the Twins, the basic necessities were met but material needs did not wield great influence. Times changed, shortages crept in. When it became difficult to fulfil the needs of life, attachments began to sprout. Soon power began to manifest itself. Life became disorganized.

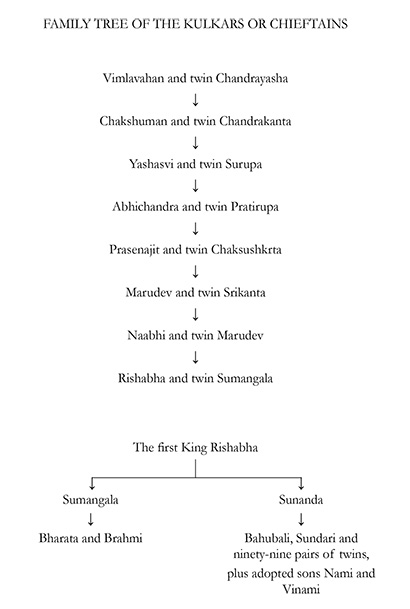

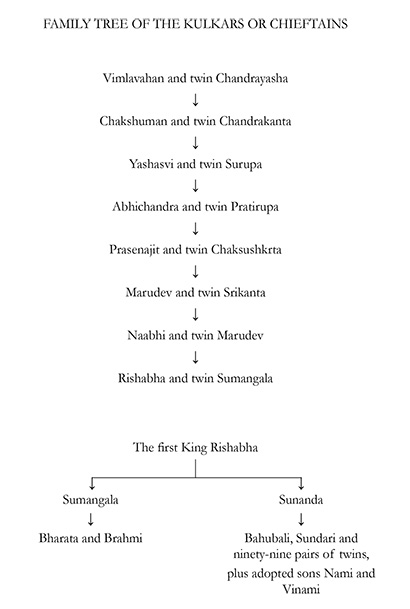

When there is paucity, exploitation, subjugation, intolerance or quarrels, then the need for organization is felt. This situation gave rise to the need for chieftains as leaders and, for a long time, the chieftains or Kulkars ruled organizing society into a structure. However, the problem of paucity kept growing. It became increasingly difficult to fulfil ones basic needs from the Kalpavriksha alone. The twin problems of power and attachment increased. Twin pairs started exercising authority over all trees.

On studying closely both human nature and its inclinations, it seems that paucity acts as an impetus to the growth of feelings of ownership and possession. They are the very same traits of attachment and desire that destroyed the organization under the small chieftains. In order to find a solution to the problem, Chief Naabhi established a kingdom and anointed Rishabha as the first king. The foremost task of the king and his ministers was to make available, and equitably so, the basic necessities of life. In the absence of equitable distribution, crimes increase. When wealth is managed equitably, then the desire to commit crimes reduces.

The kingdom of Rishabha was under the influence of the Age of Twins. At that time the feelings of attachment and power were still sprouting, so while there were occasional incidents of theft and robbery, no major offence ever took place and there was yet no criminal in society. In a way Rishabha was a king of a society that was not used to being ruled over. Material goods were few and so the people were largely free of the desire to possess. Also, self-discipline was the order of the day. Familial relationships were just beginning to be formed and understood, so even on that front, the bonds were not yet very strong.

No one had imagined the existence of servants or slaves and so every human being had a strong sense of self-worth. There was no conflict of interests between people and there was an ease in their interaction, which was free of doubt and suspicion of the other. Minimal, clean and natural food was consumed and mans mind and body were largely free of disease and violence. From the modern perspective we could say that since there was not much variety of goods available, the society that Rishabha became king over could be considered underdeveloped. But the mind and thoughts had evolved, so in that sense it was a highly developed society. Education through learning or teaching had not yet started but discerning perception had been cultivated in great measure.

Bhagwan Rishabha taught the people the use of raw materials and how to develop their skills. But after institutionalizing the affairs of the state, he left it all in the quest for his soul. He became a monk and did penance for many days before he was enlightened and could perceive the soul. Since then he became an advocate of the soul. He was the first one of this era to not just experience the soul but also tell the world about it. The epic presented here has glimpses into many fundamentals of development as well as historical events of the time.

These verses were born out of a special imaginationnot only for academic research or for peoples recitation. Some years ago Gurudev Tulsi had told me, Write a poem on Rishabha. It should not be just poetry but also instructional for the soul. It should not be just instructional for the soul, it should also be poetry. To capture that was not easy, but I have never believed any of my Acharyas suggestions to be difficult and so I set forth. The simplicity of the story gives the experience of a sermon and the rich variations in the moods lend the experience of poetry.

The words give the pleasure of a sermon while the suggestions and nuances offer the delicacy of poetry. In the year 1990, during the chaturmas in Pali, this poem began to take shape. It was completed in Ladnun in the year 1995. Work on it was dictated by routine. To edit the Agamas was the primary job at hand. This would go on in the afternoon.

The early mornings would be spent in reading and meditation followed by addressing the people in pravachan. Some time would be spent deliberating over the progress and problems of the community. The time for writing Rishabhayan was after dinner and before sunset. Sometimes there would be half an hour available, sometimes twenty minutes. I liked keeping that time for myself, to be in solitude, but often someone would come to discuss a matter that was necessary and my time would get cut into. Our stay in Delhi in the year 1994 went by with practically no work.

Sometimes two verses would get written, sometimes one and sometimes three or four. In one way it can be said that this poem came into being in a mechanical fashion. Poetry cannot be mechanical. Only when emotions and the imagination arise can poetry be composed. My situation, however, had been different. Yet the poem was completed.

The reason for this was Acharya Tulsis desire and inspiration. I deem it my good fortune that I was able to complete the poem and present it to him. I was fortunate to see Gurudevs joy also. With Gurudev, I wish I could have deliberated on the poem. That desire remains unfulfilled. In this world of creation-destruction-permanence, to visualize the satisfaction of every desire is by itself an excess.

Next page

To the One who is without end, is of ever-flowing wisdom, eternal, and whose abode is eternal To the One who is engrossed in the soul and the supreme teacher, the first Tirthankara Rishabha I offer my salutations To the One who was single-minded in penance and compassionate to his kith and kin. In his family was born Emperor Marichi Kumar who was reborn as the last Tirthankara Mahavira Those people are worthy of obeisance who strove to advocate human effort and purity of the soul In this line comes Acharya Bhikshumay his fame spread CONTENTS

To the One who is without end, is of ever-flowing wisdom, eternal, and whose abode is eternal To the One who is engrossed in the soul and the supreme teacher, the first Tirthankara Rishabha I offer my salutations To the One who was single-minded in penance and compassionate to his kith and kin. In his family was born Emperor Marichi Kumar who was reborn as the last Tirthankara Mahavira Those people are worthy of obeisance who strove to advocate human effort and purity of the soul In this line comes Acharya Bhikshumay his fame spread CONTENTS  The story of Rishabha is the story of the beginnings of Indian civilization. History rests on limiting shores; in the mystery of prehistoric times many universes lie hidden. On the foothills of the Himalayas, a civilization was being born. The Twin Age, or the primitive period, was coming to an end. From dwelling on trees, man was coming down to till the earth to make a living.

The story of Rishabha is the story of the beginnings of Indian civilization. History rests on limiting shores; in the mystery of prehistoric times many universes lie hidden. On the foothills of the Himalayas, a civilization was being born. The Twin Age, or the primitive period, was coming to an end. From dwelling on trees, man was coming down to till the earth to make a living.