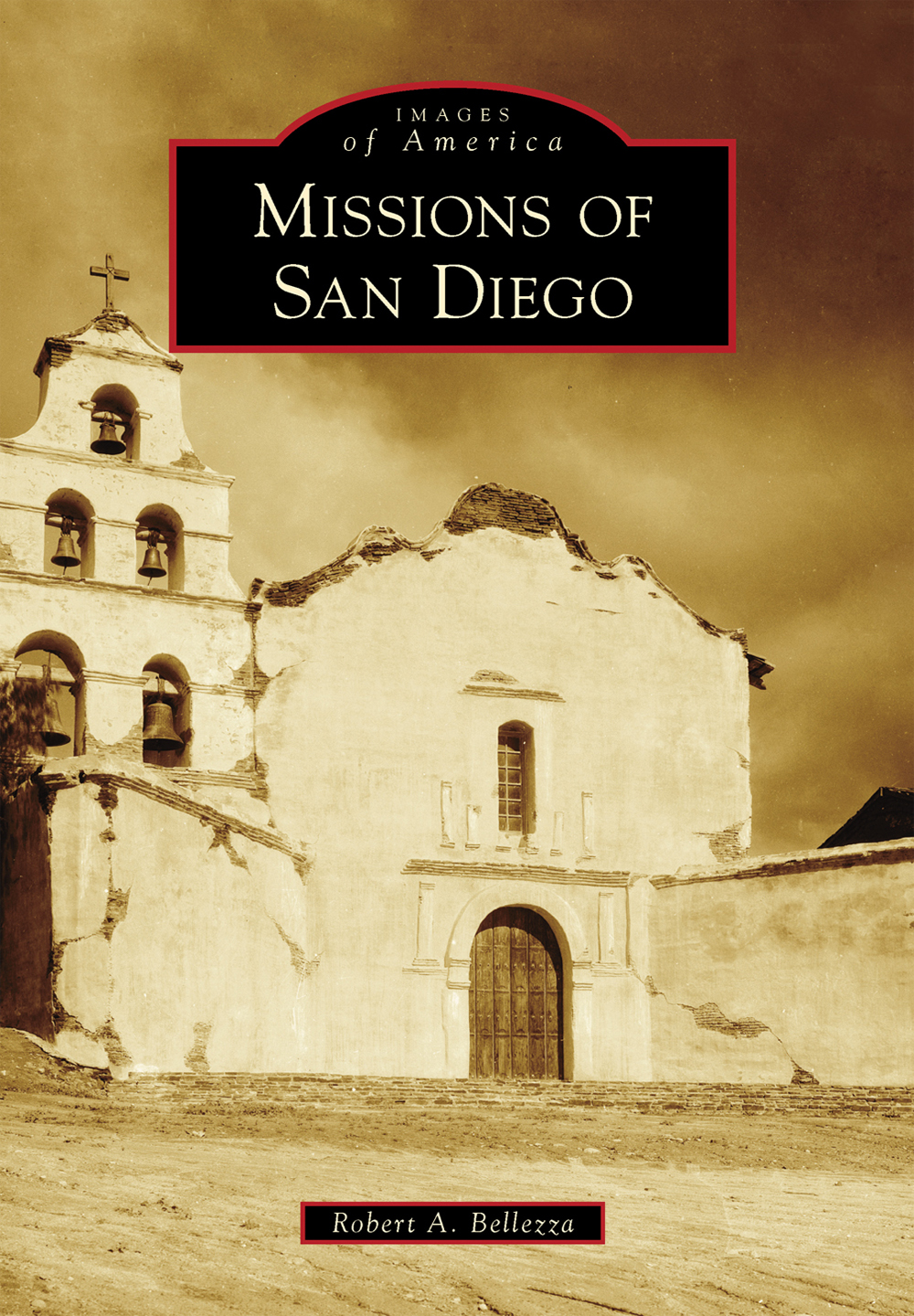

IMAGES

of America

MISSIONS OF

SAN DIEGO

A memorial cross was raised at the 1769 site of Mission San Diego de Alcal, the first California Spanish mission. The site is where Fr. Junpero Serra dedicated the mission and began the first colony of Alta California claimed by Spanish discovery parties. Established at San Diegos Presidio Park and depicted here in a vintage postcard view, the mission was relocated to its present site in 1774. (Authors collection.)

ON THE COVER: Mission San Diego de Alcal is pictured in a glass plate from about 1928. Many historic buildings have been restored, recognized, and modernized over many years to preserve all of Californias original landmark missions. (Authors collection.)

IMAGES

of America

MISSIONS OF

SAN DIEGO

Robert A. Bellezza

Copyright 2013 by Robert A. Bellezza

ISBN 978-0-7385-9683-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439643976

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013932445

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

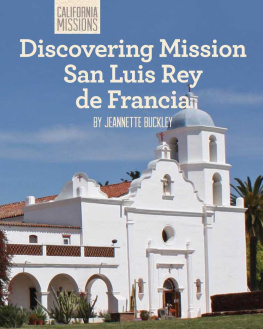

To my daughter, Tara, and her husband, Don Etheridge, who are raising my twin grandsons and choosing fields of educational work in the San Diego area, a mile or so from Mission San Luis Rey de Francia.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Collection has supplied the majority of images within this volume and makes possible a review of Californias founding architectural landmarks practically lost through centuries of age, deterioration, and neglect. Californias mission buildings were rescued only after the majority had suffered irreversible weathering and ruin to their adobe walls. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and photographers from the New Deal programs starting in 1933 documented the progress or decay of the many iconic structures through the Historic American Building Survey. Unless otherwise indicated, all images are courtesy of the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey.

By the beginning of the 20th century, there had been efforts made to preserve the earliest missions, often built and decorated entirely by California natives. Several photographs within this volume are released for the first time from the authors collection and from the Anderson familys collection of vintage glass plates. Many up-to-date mission photographs featured in Missions Past and Present: Touring El Camino Real are from the authors visits to each area beginning in 2004.

We are truly pleased our books release coincides with the 300th anniversary year of Fr. Junpero Serras birth. Miguel Josep Serra (Junpero was his chosen religious name) was born on November 24, 1713, in Petra, Majorca, one of the Balearic Islands, located some 150 miles off the coast of the Spanish mainland.

INTRODUCTION

The first encampment atop a hill high over San Diegos harbor was established by two land and two sea expeditions and became the first Spanish mission and presidio established in Alta California. A large cross was raised in the sand by Fr. Junpero Serra, Franciscan friar and visionary mission president, who celebrated Mass and the founding of the Mission San Diego de Alcal on July 16, 1769. Eventually, 21 Spanish missions and their adobe, brick, and stone buildings would grow to productive colonies lasting decades. In recent times, these monumental landmarks of Californias heritage have been considered an invaluable part of its history, and all mission buildings have been faithfully restored.

SPANISH GALLEONS AND COLORFUL CONQUISTADORS

The first Spanish settlers adapted the native style of traditional thatched tule reed dwellings on rudimentary earthen floors as the first missions, or they built simple ramadas, brush- and mud-encased enclosures. San Diegos aboriginal peoplethe Kumeyaay, Tipai, and Ipaiwere people of white sage and the eagle, who lived for millennia within the diverse microclimatic regions of the Golden State. California native tribes had developed many distinct cultures with unique languages.

In his initial voyage in 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo anchored the San Salvador off Catalina and the islands of the Santa Barbara Channel on his journey to the north, naming Cape Mendocino. In San Diego, Kumeyaay people first responded to Cabrillo by wounding three of his men with arrows. Cabrillo, taking two younger natives aboard, made an effort to communicate with them before releasing the youngsters back on land with new clothing. The message was relayed that he was a peaceful man. Cabrillo had been able to befriend the Chumash, native people of the Channel Islands and Santa Barbara, and they offered food and other provisions to the seafarer.

The official founding of Montereys harbor in 1602 was consigned to an adventurous Spanish merchant, Don Sebastin Vizcano. Carefully charting the entire coast, he claimed possession for Spain, either naming or renaming most ports. The land yet unexplored, Vizcano declared Montereys northern port as ideal and the best possible capital for Alta California. Mexico City, the Spanish capital of the New World, entered a period of prosperity at the time of Vizcanos early report but curiously allowed the passage of two centuries before showing interest in exploration to the north.

Privateers and seafaring plunderers under foreign flags had begun to challenge the Spanish holdings, and the voyages made by Capt. James Cook to Tahiti and Hawaii had brought attention to the New World by 1769. Spain had chosen the governor of Baja California, Don Gaspar de Portol, to muster a first land expedition and venture into Alta Californias expansive territories to make permanent Spanish settlements. Joining legendary Fr. Junpero Serra, two mission colonies were planned, one for San Diego and another in Monterey, each following Vizcanos earliest descriptions. The quest for Monterey began after Father Serra founded Mission San Diego de Alcal in 1769 and a new land expedition had assembled, including friars, an engineer, carpenters, Spanish leather-jacket dragoons, and Baja Indian interpreters followed by a pack train of mules. The overland discovery party passed Santa Monica and Santa Barbara, extending a trail named by the friars El Camino Real, or The Royal Way, an ancient path blazed by missionaries honoring Carlos I, king of Spain until 1556. Originally, the path reached thousands of miles into the Guatemalan and Mexican jungles, and El Camino Real would now connect Mexico City to Monterey.

Portol sent search parties out from his campsite near Monterey to discover the features of the coastline, but they were unable to identify Montereys great harbor. The search ventured into bitterly cold, snowy weather as they attempted to signal from Carmels shore to a packet lost at sea. With little hope for supplies, the Portol expedition turned back to the San Diego settlement and the remaining eight colonists, who were also surviving with little food. Portol ordered plans for the galleon San Antonio to return to San Diegos harbor. Despite hardships, a second expedition led by Portol reached Monterey by land.

Next page