Compilation copyright 2013 The Moth. Copyrights in the individual works retained by the contributors.

ITS TRICKY

Words and Music by Joseph Simmons, Darryl McDaniels, Jason Mizell and Rick Rubin Copyright (c) 1986 Protoons, Inc. All Rights Administered by Universal Music Corp. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information address Hyperion, 1500 Broadway, New York, New York 10036.

eBook Edition ISBN: 978-1-4013-0596-3

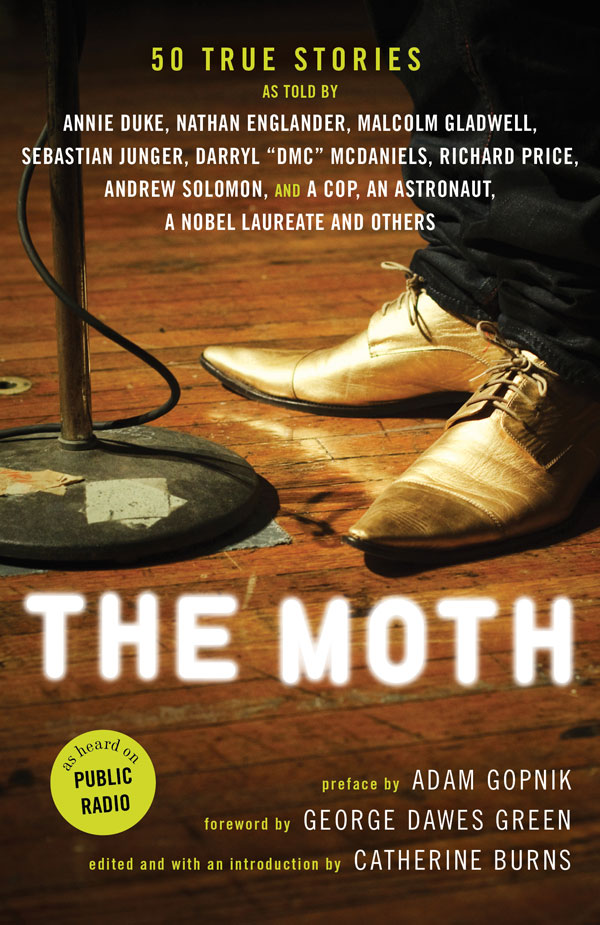

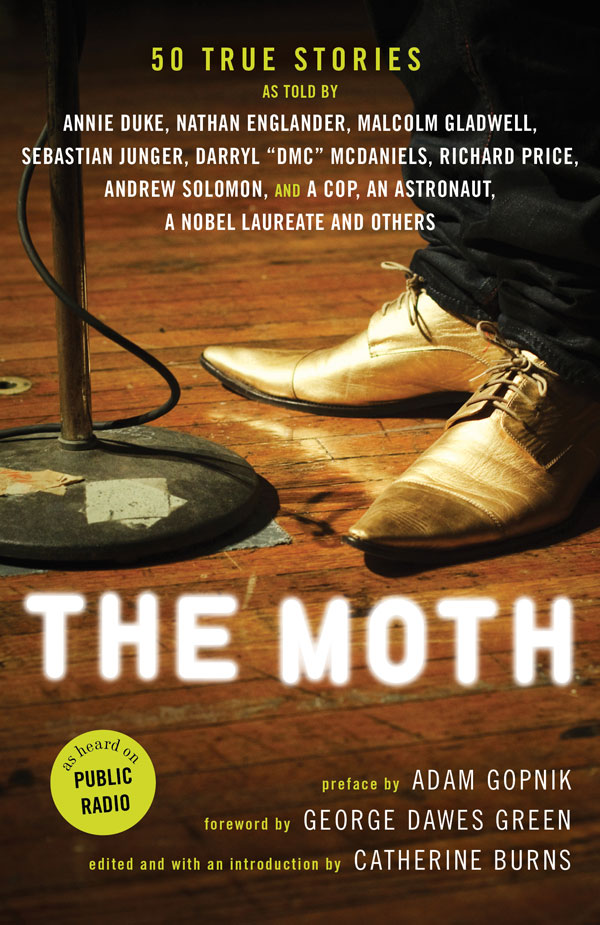

Cover design by Laura Klynstra

Cover photograph by Sarah Stacke

First eBook Edition

Original trade paperback edition printed in the United States of America.

www.HyperionBooks.com

For Wanda

W ho knew that what New York needed was a front porch? That the secret desire hidden in the hearts of hipsters and banksters alike was a chance to sit after dinner in a screened-in space, to escapeor maybe just enjoythe summer heat, and there, in the dark, lit by a single lamp with its attendant insects, swap stories, tell tales? Who knew that what we really wanted was one shared place where everyone from a kid off the street to a cop just off the beat to Salman Rushdie could tell about this weird thing that happened: Did I tell you this already? No? Well, you remember that time I went round on Christmas to Uncle Norms

Storytelling, story-sharing, tale-bearing in the good sense, yarn-spinningwho knew that what New York (and now the nation; well get there) needed was that?

Well, the men and mostly women of The Moth knew. This book relates what is itself an improbable story, a yarn spun about how The Moth sprang from a simple idea of George Greens, slowly grew, and then eventually became a national phenomenon.

But the deeper questions are: Why now? Why here? And, above all, why does it work? What is it about this improbable form that The Moth has made its own and shared with the worldthe timed, short personal story, rooted in reminiscence and memoir, distinctly unprofessional even when offered by a prothat vibrates with its era?

A lot of its success has to do, as always in life, with much preparation and calculation beneath the seeming spontaneity. For all their seeming inconsequence and improvisational air, a good Moth story is as carefully prepped and cultivated as a bonsai tree, with the same understanding that the miniature form, far more fragile than the bigger kind, needs more constant tending. You have a little stage space to waste in a two-hour play, but theres not a second that doesnt have to count in a ten-minute story. The producers and directors of Moth eveningsan astonishing array of those mostly female overseers, who somehow combine the role of effusive cheerleader and hard-headed theater criticrun the stories, work the stories, over and over, until that thing you hear, though never written down, is incised on the storytellers consciousness for good, with all its inner twists and turns.

That relentless preparation may be, for the arrogant writer-type who thinks he already knows all there is to know about storytellingi.e., methe most difficult, and then in the end the most rewarding thing about the Moth process. A good story, were reminded, is shaped, plotted, rehearsed. The best guy on the porch was planning his tale right through dinner. A good story needs an A plot and usually a B plot, and then, if its to levitate the room, to use the lovely expression the women of The Moth use themselves, it almost always needs some last rising touch, a note of pathos or self-recognition or poetic benediction, to lift the story, however briefly, into the realm of fable or symbol.

Three more Cs spring to mind to encircle the mystery of The Moth. A lot of the magic of the Moth story is confessional: Everyone likes to talk about himself, to be sure, but the stories we like to hear most are the ones that you would think we would be most unwilling to tell. The human need for confession in the presence of others, left mostly untended by the churches these days, is fulfilled by the Moth occasion. An uncanny number of the best Moth stories are admissions, even apologies, frank, candid (I spent Christmas in a transgender bar or When I was fourteen, I shot my friend by accident). And the audience listening implies, by the perfect silence of their attention, that they are raptright there with you. Throughout even a self-humiliating Moth story, one hears the rarest thing: the sound of an audience keeping an open mind. Then often laughterand always, applausecloses the circuit. The unspeakable or embarrassing thing admitted turns out to be not so bad, maybe even surprisingly commonplace. We didnt all insult James Brown or get busted making hooch in Attica, but life presents relentless difficulties and complexities and humiliations even to the luckiest of us, and we applaud warmly as if to say, I know. The audience doesnt release its breath as it does at a high-tension tragedy, or applaud in culminated pleasure as at a good musical. No, the audience pauses, reflects for a bare half moment, and then erupts in the pleasure not of seeing a thing accomplished but of hearing a truth shared. Some ancient ritual of expiation seems to be taking place: thats okay, the exhalation says, what happened to you, however hair-raising, and the Moth stories that have been told about escapes from prison, accidental shootings, and near-death experiences are now part of what has happened to us all.

The second C is that of comedy. Perhaps the hardest thing those Moth story directors have to teach the storyteller is that the laughter will come only if there are no self-conscious jokes. This isnt stand-up, they say, in pleasant effect, to the guy who, with a microphone suddenly in his hands, wrongly thinks himself a second Seinfeld. (Me, again.) The laughter provoked by a Moth story has to be ethical laughter: not the laughter of a taboo transgressed, but the laughter of a truth revealed. And nothing is more helpful to a storyteller who may also be, in mufti, a pro writer than this reminder that the ethic of all storytelling is credibility, truth.

Much has been made of the human need for narrative, but, truth be told, stories dont make us better people. But they do make us truer writers.

My own Moth experience came along, for instance, at a moment when I often felt mired in the damp, soggy marsh of the four-thousand-word essay, with its exhausting, sapient certainties and predictable drop-cap caesuras (Edmund Burke was born in). The pressure of Moth storytelling made me newly aware of what propulsion can do for a paragraph. It reminded me that drama and pacing and even suspense could be wooed from the slightest materials, and that the key to good writing (one key, anyway) is that the reader should never look back. (Even Proust, for all his elaborating, is a spiraling but not a circular writer. We may move round and round, but we press ahead.) Every essay is really a story, and every story, truth be told, shares the same ethic, the same motto. The great storyteller Frank OConnor defined it best, saying once that every good story should end, in spirit, with the exact same words: And everything that ever happened to me afterwards, I never felt the same about again. (He actually got to use that ending, once.) In this book of Moth stories, that test of significance, of meaning, is met again and again. There are very few of these well-told tales that dont have those words as an invisible addition. You can mouth them to yourself as the story ends:

Next page