William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2016

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Text Ben Fogle 2016

Photographs Individual copyright holders

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material, the author and publisher would be grateful to be notified of any errors or omissions in the above list that can be rectified in future editions of this book.

Ben Fogle asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover photographs: bottom Matthew Ward/Getty Images; top JLR Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008194222

Ebook Edition October 2016 ISBN: 9780008194239

Version: 2017-05-04

To Willem

CONTENTS

LAND ROVER

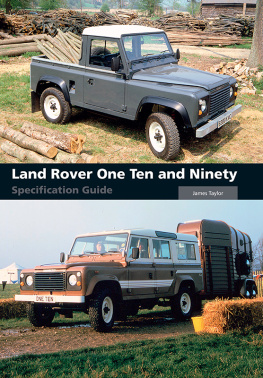

The Series I, II, IIa, III, 90, 110 and Defender are all members of the iconic boxy Land Rover genre, first produced in 1948, with the current version called Land Rover Defender. To avoid any confusion, in this book I will sometimes refer to them all using Defender as a collective noun. Please dont hate me.

Lode Lane, Solihull is a flurry of activity. The brick walls are still covered in camouflage paint to disguise the factory from German air raids. The waters of the Birmingham canal flow close by, ready to extinguish any fires from falling bombs. Nearby a field has been transformed into a jungle track to test the vehicles. On the factory floor inside, a team of workers are riveting aluminium plates and fixing axles to chassis on cars in various states of deconstruction. This is the famous Solihull Land Rover factory and the workmen are building some of the most iconic cars ever built, the Land Rover Series I, a car that changed the world. But this is not 1948. It is 2016 and I am watching third-generation factory workers making Series I vehicles on the same patch of land that their grandfathers had once done.

Just a few months before, the world had mourned as the very last Defender, the evolution of the Series I, rolled off the factory line. The lights went out on 67 years of iconic history. It had been the end, but now I was back at the very beginning for the rebirth. Where most evolve and advance, here at Lode Lane, workers were using decade-old tools and technology to regress to a simpler time. To make a vehicle born out of post-war rationing to help a country rebuild. This is the reborn project at Land Rover where buyers can spend more money on a new 68-year-old vehicle than a top-of-the-range sports car.

As I bounced, cantilevered and splashed along the very same jungle track once used by the Wilks brothers to demonstrate the capabilities of these workhorse vehicles, I couldnt help but marvel at the ageless charm of these iconic cars. Regressive progression. Nostalgic advancement. The new old. Was this the rebirth? Had the Land Rover ever really died? Or was this really the resurrection we had all dreamed of?

It is an oxymoron but a fitting metaphor for the story of the greatest car ever made.

Do not go where the path may lead,

go instead where there is no path and leave a trail

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Sometimes you dont know what youve got until its gone.

At 9.30am on 29 January 2016, the 2,016,933rd Defender rolled off the production line at Land Rovers factory at Lode Lane, Solihull, on the outskirts of Birmingham. It marked the end of 67 years of continuous production of the worlds most famous vehicle. The final Defender.

In all those years, the workhorse Defender had served farmers and foresters, armies and air forces, explorers and scientists, construction and utility companies in fact, everyone who needed a good, honest vehicle that would do a good, honest job anywhere in the world. And there were a lot more people who bought one just for fun, too for its sheer brilliant off-road ability and austere utilitarian attitude that made it so different to the rest of todays homogenised, jelly-mould automotive offerings.

Jerusalem was sung through the factory line as generations of engineers, mechanics and factory line workers paid tribute to the Land Rover Defender. This was a funereal send-off for a much-loved car that had conquered the planet. Media, journalists and film crews had descended from around the world to record this death knell. The world held its breath as the last ever Defender was driven silently out of the building.

This was an end that was marked by tears and sorrow, as Land Rover enthusiasts bade farewell to a familiar friend and the historic production line that had produced it fell silent.

The world mourned. This was the day the real Land Rover, the successor to the Wilks brothers 1948 original, died.

It is said that for more than half the worlds population the first car they ever saw was a Land Rover Defender. As quintessentially British as a plate of fish and chips or a British bulldog, the boxy, utilitarian vehicle has become an iconic part of what it is to belong to this sceptred isle. It is a part of the stiff-upper-lipped British psyche; it never complains, and neither do we.

You climb into a Land Rover literally; in fact some people even need ropes to hoist themselves up into the rigid seats. The doors dont seal properly, and freezing cold rainwater, overflowing from the cars gutter (they really do have a gutter) cascades down your neck as the flimsy aluminium door invariably closes on the seat belt that dangles out of the door. The dashboard consists of a series of chunky black buttons and two analogue dials. Without heated seats, climate control options are freeze or fry. The windows ALWAYS mist, even if you hold your breath. I have to pull up a metal antenna from the bonnet to pick up radio, which I can only receive while driving at 30mph. If I crank her up to her limit of 60mph, the noise from the engine, gearbox, transfer box, differentials, tyres and the wind is deafening, and too loud to have a conversation let alone listen to anything from the speakers. There is no coffee-cup holder or hands-free. The gears grind and the seats cannot be tilted.

So on the face of it there is not much going for the Defender. It is noisy, uncomfortable, slow, uneconomical and, according to the USA, dangerous. So why is it that I, along with millions of other people around the world, am so hopelessly, obsessively in love with this car?

The Land Rover is an integral part of the fabric of our society, a part of the furniture. Nothing lasts forever, but some things come close. The Defender has survived the decades largely unchanged. It transcends fashion while somehow epitomising it. It has an ability to neutralise rational thought or expectation, and it has avoided the homogenisation of our vehicles in modern times.

The Defender is a beacon of safety and security, too. It is favoured by the military, the police, the fire service, NGOs, the UN, the Royal Palace, the Special Forces and explorers alike. These vehicles have discovered new regions, won wars and saved lives. Across the world, the Land Rover symbolises durability and Britishness, with her diversity and rigidity. It is estimated that three-quarters of all Land Rovers ever built are still rattling noisily across country somewhere in the world.