BULFINCHS

MYTHOLOGY

Bulfinchs

Mythology

by Thomas Bulfinch

Introduction by Stephanie Lynn Budin, PhD

CANTERBURY CLASSICS

San Diego

2014 Canterbury Classics/Baker & Taylor Publishing Group

Copyright under International, Pan American, and Universal Copyright Conventions. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage-and-retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright holder. Brief passages (not to exceed 1,000 words) may be quoted for reviews.

Canterbury Classics is a registered trademark of Baker & Taylor.

All rights reserved.

All correspondence concerning the content of this book should be addressed to

Canterbury Classics

10350 Barnes Canyon Road, Suite 100

San Diego, CA 92121

Inconsistencies in spelling and punctuation throughout remain in order to preserve the original flavor of Thomas Bulfinchs text.

eISBN 978-1-62686-277-7

CONTENTS

BULFINCHS

MYTHOLOGY

B ulfinchs Mythology was the first book in the English language to make the myths of the Greeks and Romans accessible to a public not trained in Greek and Latin. In addition to his lively and enjoyable versions of the classical myths, Bulfinch also gathered together the great romantic tales of Britain and France, presenting the epics of King Arthur, Emperor Charlemagne, the noble Orlando, and even the Welsh hero Pwyll. As such, this book was the primary resource for the study of ancient mythology for over a century, and was the most commonly consulted resource for classical and medieval literature throughout the Victorian Age in the English-speaking world.

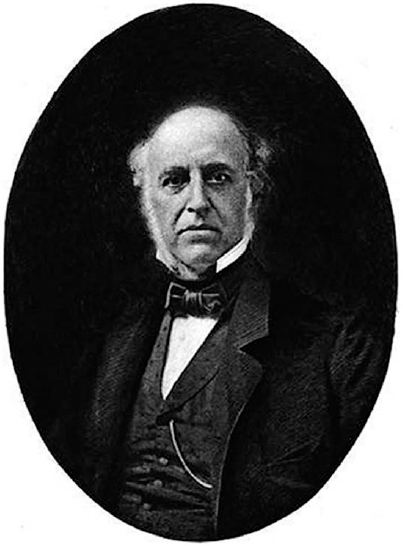

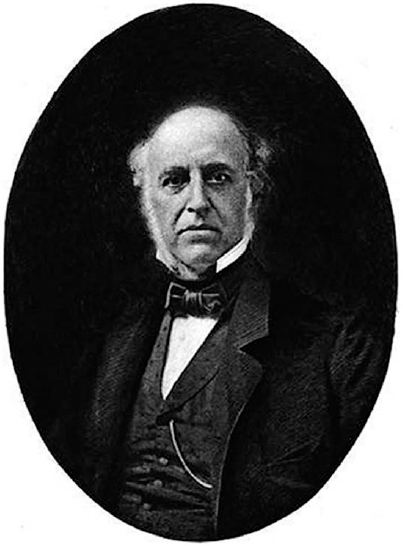

Thomas Bulfinch was born on July 15, 1796, in Newton, Massachusetts. His father was the eminent Boston architect Charles Bulfinch, who worked on the U.S. Capitol building and is responsible for its domed center, as well as the capitol grounds. The son of a Harvard graduate, Thomas was exceptionally well educated. He studied at Boston Latinreceiving an early education in the classics, Phillips Exeter Academy, and finally, in good family tradition, Harvard University. He achieved his university degree in 1814, and taught briefly at his alma mater Boston Latin before settling down as a clerk at the Merchants Bank of Boston, a position he held until his death. Devoting himself more to his hobbies than his career, he served as secretary of the Boston Society of Natural History, and he wrote books for school-age readers, including Hebrew Lyrical Poetry (1853), The Boy Inventor (1860), Shakespeare Adapted for Reading Classes (1865), and Oregon and El Dorado (1866).

In the mid-nineteenth century, Bulfinch wrote the three books that permanently enshrined him in the annals of mythographyThe Age of Fable in 1855, The Age of Chivalry in 1858, and Legends of Charlemagne in 1863. By the start of the twentieth century these three titles were bound together into the single volume you now have before you. All three works aimed to present the legends of old to a nineteenth-century audience in a manner as simple and enjoyable as possible, for Bulfinch believed that literature could only be properly understood if the reader could comprehend the various allusions made in the text. As he claims in his preface to the Age of Fable:

Without knowledge of mythology much of the elegant literature of our own language cannot be understood and appreciated. When Byron calls Rome the Niobe of nations, or says of Venice She looks a Sea-Cybele fresh from the ocean, he calls up to the mind of one familiar with our subject, illustrations more vivid and striking than the pencil could furnish, but which are lost to the reader ignorant of mythology.

A similar sentiment prevailed for the Age of Chivalry, which recounts the tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, as well as related texts that pertain to the legendary history of Britain. Once again, the main purpose of this endeavor was to provide the reader an enjoyable means of learning the antecedents of many literary references, such as Spensers Faerie Queen and Tennysons Idylls of the King. Legends of Charlemagne rounded out this classical education by providing one final series of stories that dominate the symbolic vocabulary of English literature.

In the early twenty-first century, Bulfinchs Mythology is interesting for two reasons, the first being that the tales are interesting and delightful, and knowledge of them doesas Bulfinch claimedimprove ones ability to appreciate the high arts of Western Europe and its descendants. The other reason is Bulfinchs aims, prejudices, and understandings provide a fascinating glimpse into the Victorian mentality.

THE AGE OF FABLE

T his work served as the standard reference for classical mythology for over one hundred years in the Unites States and Britain. It is, as Bulfinch described it, a compilation of retellings of the myths in such a manner as to make them a source of amusement. He realized that very few individuals would have the means or inclination to learn Greek and Latin and thus be able to read the fables in their original languages. Furthermore, he believed that direct translations of the works in question were also impractical, because they assumed a preexisting knowledge of the body of myths, such that one had to know mythology in order to learn mythology. Instead, Bulfinch chose to retell the myths, arranging them in a coherent fashion, adding annotations where necessary, and beginning with an introduction to familiarize the reader with the deities and sources in question.

It is evident that Bulfinch did indeed remain very close to his sources, which were for the most part Ovids Metamorphoses and Virgils neid. The similarity between text and retelling comes across well in Bulfinchs description of creation:

Before earth and sea and heaven were created, all things wore one aspect, to which we give the name of Chaosa confused and shapeless mass, nothing but dead weight, in which, however, slumbered the seeds of things. Earth, sea, and air were all mixed up together; so the earth was not solid, the sea was not fluid, and the air was not transparent. God and Nature at last interposed, and put an end to this discord, separating earth from sea, and heaven from both. The fiery part, being the lightest, sprang up, and formed the skies; the air was next in weight and place. The earth, being heavier, sank below; and the water took the lowest place, and buoyed up the earth.

Next page