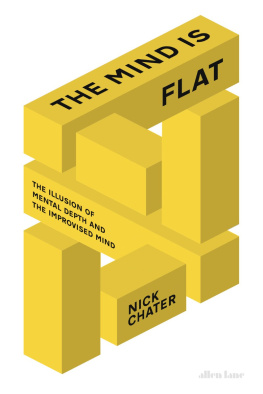

Chater - The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind

Here you can read online Chater - The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: UK, year: 2019;2018, publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Chater: author's other books

Who wrote The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Mervyn Peakes Gormenghast Castle is one of the strangest settings for a work of fiction vast, misshapen, ancient, crumbling and architecturally idiosyncratic. Peakes visual imagination was wonderful he was an artist and illustrator as much as a writer and his sharp and striking descriptions create a sense of a world of solidity, richness and detail. As you read his novels Titus Groan and Gormenghast, Gormenghast Castle begins to inhabit your imagination. Over the years, some particularly committed, and perhaps slightly obsessive, readers have tried to piece together the geography of the castle from its scattered descriptions. Yet this appears to be an impossible task: the attempt to draw a map, or build a model, of Gormenghast Castle leads to inconsistency and confusion the descriptions of great hallways and battlements, libraries and kitchens, networks of passages and vast, almost deserted wings cant be reconciled. They are as tangled and self-contradictory as the inhabitants of the castle itself.

Peakes verbal magic aside, this should not be surprising. Creating a fictional place is a bit like setting a crossword. Each description provides another clue to the layout of the castle, city or country being imagined. But as the number of clues increases, knitting them together successfully soon becomes extraordinarily difficult indeed, it rapidly becomes impossible, both for Gormenghasts readers and for Peake himself.

Troubles with the coherence of fictional worlds go far beyond mere geography, of course. Stories have to make sense in so many ways: through consistency of plot, character and a myriad of details. Some authors go to inordinate pains to minimize such mishaps: J. R. R. Tolkien set The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in a world Middle-earth with a detailed history, mythology and geography, complete with maps, to say nothing of invented Elvish languages with extensive vocabulary and grammar. At the other extreme, Richmal Crompton, author of the stories of the charmingly roguish schoolboy William Brown, sketched in the details of her stories with considerable abandon, and cheerfully admitted flagrant inconsistencies (the heros mother is sometimes Mary, sometimes Margaret; his best friend is either Ginger Flowerdew or Ginger Merridew).

So inconsistencies are one thing that make fiction different from fact: the actual world may seem puzzling, paradoxical and downright contrary, but it cannot actually be self-contradictory; and while a description of a castle or a country can turn out to make no sense, an actual castle or country is, by its very existence, perfectly consistent all the facts, distances, photographs, theodolite measurements, satellite imagery and geological soundings must yield a coherent picture because there is just one unique, actual world. But with fictional worlds, avoiding inconsistency requires incredible vigilance. Despite the painstaking efforts of a brilliant and remarkably retentive mind, Tolkiens Middle-earth has yielded a haul of apparent inconsistencies, when scoured by its huge fanbase.

Fictional worlds, even the immensely detailed worlds of Peake and Tolkien, are notable too for their sheer sparseness. In real life, everyone has a specific birthday, fingerprint and an exact number of teeth. In fictional worlds, most characters have none of these properties, or any of a million others, whether significant (having a recessive gene for haemophilia) or trivial (the precise family relation to Elvis).

But, of course, the scarcity of information in fiction is much more profound than this. Consider again Anna Karenina, whose public persona, relationships and, perhaps, sense of her own identity, depend on her beauty. Yet what did she look like? Artist and celebrated book-cover designer Peter Mendelsund points out that Tolstoy says astonishingly little that she has thick lashes, a thin down of hair on her upper lip and scarcely more. Is she tall or short? Blonde, redhead or brunette? Blue-eyed or brown-eyed? The astonishing thing is not that Tolstoy tells us so little, but that we dont notice and, still less, care. We can read the book with the subjective feeling that it is the story of a flesh-and-blood, three-dimensional woman, rather than a blurry stick figure, but Tolstoy tells us almost nothing about which flesh-and-blood, three-dimensional woman.

One might retort, of course, that literary fiction is not about the physical appearance of characters, but about the inner life of the mind. Yet the truth is that Annas mind is just as vaguely sketched as her body: what sort of person is Anna, exactly? How would it feel to have a conversation with her? How does she view the Russian state and its vast inequalities? Is she both defiant of, and crushed by, the opprobrium she receives in pursuing her affair with Vronsky? The wonder of Tolstoys novel is that these questions are not answered, but are tantalizingly and fascinatingly open: we can read Anna in a variety of ways: as heroic, obsessive, romantic, defiant, wild, oppressed, loving, or cold, in various degrees and combinations. But this very openness implies, of course, that Annas characteristics, whether physical or mental, are not pinned down by the text of the novel.

Consider, now, the real Anna we imagined in the Prologue. Suppose, indeed, that the novel were novelized biography, rather than pure fiction. Then all those missing facts about Anna (her precise physical appearance, her genome, her relationship to Elvis) would all be completely well defined. We might be able to figure some of them out, through concerted research (e.g. careful genealogical analysis might reveal a common ancestor with Elvis in, perhaps, seventeenth-century Kiev); other facts (e.g. her height on her eleventh birthday) might be neither known nor knowable, given the surviving traces from her life. But is there a true reading of Annas life, a precise delineation of her personality traits, motives and beliefs, if we only knew more?

Recall the two characteristics of fiction we mentioned earlier inconsistency and sparseness. If Anna were to explain her own inner life, she would surely be as jumbled, incoherent and self-contradictory as Mervyn Peakes Gormenghast Castle. Her explanations would be inherently sparse she might have little idea of her views on many aspects of Russian society, the people around her, her own goals and aspirations, and many other topics she has scarcely considered. While the real Anna really would have a family relationship to Elvis, she would surely not have precisely defined views on the merits of different modes of Russian agricultural reform or the future of the Tsar. She could, of course, create and articulate opinions, on demand. But these opinions would themselves be both vague and liable to fall into self-contradiction. The real Annas mind would be just as much a work of fiction as the fictional Annas mind; our own minds are no more real. Whereas the fictional Anna is a sketchy and contradictory character created by Tolstoys brain, a real Anna would be an equally sketchy and contradictory character, created by her own brain.

The external world is quite the opposite, of course. It is specified in complete detail, whether we know the details or not. My coffee mug was bought on a particularly day of the week and fired at a particular temperature, in a specific kiln; it has a particular weight and distance from the equator. And the real world is relentlessly consistent: for facts to hold good in the same world, they cannot be contradictory.

By contrast, our beliefs, values, emotions and other mental traits are, I suggest, as tangled, self-contradictory and incompletely spelled out as the labyrinths of Gormenghast Castle. It is in this very concrete sense that characters are all fictional, including our own. Inconsistency and sparseness are not just characteristics of fiction. They are also the hallmarks of mental life.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind»

Look at similar books to The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The mind is flat the illusion of mental depth and the improvised mind and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.