Carlisle - How to Believe: Kierkegaards World

Here you can read online Carlisle - How to Believe: Kierkegaards World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Guardian Books, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

How to Believe: Kierkegaards World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How to Believe: Kierkegaards World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

How to Believe: Kierkegaards World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How to Believe: Kierkegaards World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

How to Believe: Kierkegaards World

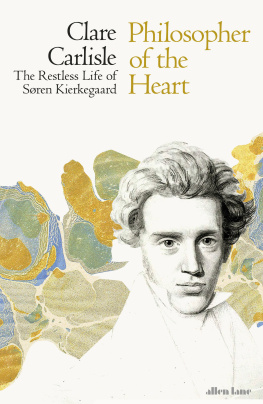

Clare Carlisle

It is difficult to categorise Sren Kierkegaard: to some readers he is primarily a philosopher, to others a Christian thinker or theologian. He was also a perceptive psychologist and incisive cultural critic. But above all, Kierkegaard was a writer. Much of his adult life was spent pacing around his Copenhagen apartment, composing out loud the sentences that he would then write down, still standing, at his tall desk.

He was extraordinarily prolific, producing on average a couple of books each year during the 1840s. Some of these are provocative, genre-defying works on philosophical and religious themes, written under a variety of pseudonyms and sometimes featuring biblical and fictional characters. Others are collections of sermon-like discourses, written explicitly for the readers spiritual edification. All are, however, unmistakably Kierkegaardian, distinguished by his eloquent and exuberant prose style, by a love of word-play, irony and paradox, and by a rare combination of sardonic wit and profound sensitivity to the human condition. Even more distinctive is Kierkegaards attempt to address his readers personally and to encourage them to reflect on their own lives.

For those reading Kierkegaard for the first time, a good starting-point is the short 1843 book Fear and Trembling, or the slightly longer 1849 text The Sickness Unto Death. Despite their daunting titles, these are among Kierkegaards most popular and engaging works. In this short ebook well look at some of the themes and ideas explored in them, although Ill touch on some of his other books too.

We may as well begin with a question that is at the heart of Kierkegaards philosophy: what does it mean to exist? In his 1846 book Concluding Unscientific Postscript which, at over 600 pages, is surely one of the lengthiest postscripts ever written he suggests that people in our time, because of so much knowledge, have forgotten what it means to exist. Even though all sorts of things exist, for Kierkegaard the word existence has a special meaning when applied to human life. This meaning arises from the fact that we always have a relationship to ourselves. For example, we can be more or less self-aware; we can wish to be other than how we are; we can trust or mistrust, like or dislike ourselves. Perhaps we can even make decisions about who we will become.

For Kierkegaard, the most pressing question for each person is the meaning of his or her own existence, which arises from this relationship with the self. Indeed, this is what might be called an existential question: it is not just an abstract intellectual question, to be posed by experts by professional philosophers, for example but a question that really matters, in an immediate and urgent way, to every human being, because it has an direct impact on choices about how to live. Kierkegaards insistence on the importance of such questioning has led him to be regarded as the father of existentialism.

When Kierkegaard writes that we have forgotten what it means to exist, his point is not so much that we have forgotten the answer to this question, but that we have forgotten about the question itself. The cause of our forgetfulness, he claims, is the ever-growing amount of knowledge. He is not arguing that knowledge is a bad thing, but pointing out that its pursuit, however worthwhile in itself, can be a distraction from existential issues. And even if we pause to reflect on the purposes of knowledge, and conclude that it should be pursued for the sake of enhancing human life, we are still led back to the question of what this life means, and why it matters.

I will explore further Kierkegaards attitude to knowledge in the next section, but we can begin to reflect on how the growth of knowledge might be linked to a neglect of the question of the meaning of our existence. This accusation is directed specifically at the modern age, and it seems to be as pertinent today as in the mid-19th century. Kierkegaards own time was characterised by an accelerated expansion of knowledge particularly of historical knowledge, including the history of the bible and of Christian doctrine, which came more and more to be viewed as human phenomena that, despite claims to articulate eternal truths, evolved through time just like other ideas, customs and institutions. An increase in knowledge was also manifest in technological developments, such as faster transportation and new methods of printing that facilitated, for the first time, a culture of mass-media. A century and a half later, of course, we now live in a world that is far more highly developed in these ways. If Kierkegaard thought he lived in a time of too much knowledge, he would no doubt say today that we live in an age of too much information.

We may now worry that such progress, in spite of all the advantages it brings, is damaging primarily to the natural world. But Kierkegaards main concern was with damage to the ethical and spiritual aspects of human life. He might even see our current focus on environmental problems as yet another factor contributing to the neglect of the question, What does it mean to exist? or perhaps as a symptom of this existential forgetfulness. From Kierkegaards own perspective, which was shaped by his Christian upbringing and beliefs, the question of the meaning of existence was ultimately a religious question since the self to whom we relate is given by God. However, as he writes in Concluding Unscientific Postscript, if people have forgotten what it means to exist religiously, they have probably also forgotten what it means to exist humanly. If Kierkegaard were simply defending traditional Christian beliefs, it would be difficult to explain his profound influence on philosophers who rejected these beliefs, such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger.

One of Kierkegaards most influential ideas is his distinction between two kinds of truth. Sometimes he describes these as objective and subjective truth; sometimes as truth that is known, and truth that is lived. According to Kierkegaard, it is the lived, subjective kind of truth that is most important to each existing human being. Implicit in this claim is a critique of traditional philosophy, for most philosophers in spite of disagreements about how to define truth, how much of it can be known, and how best to attain it have thought that truth, if it is possessed at all, is possessed in the form of knowledge.

Kierkegaard is not particularly interested in philosophical debates about whether we really know that the things we perceive exist, or whether we really know that today is Monday. With regard to the truth as knowledge, Kierkegaard tends to emphasise the absence of certainty: for example, he argues that the historical life of Jesus can only be a matter of belief, not knowledge, and he regards the Christian doctrine of the incarnation as a paradox that human reason cannot grasp. But what is most important, in his view, is the way each individual relates themselves to these beliefs, or indeed to any other beliefs, values or ideals. What matters is how beliefs are lived, from day to day and even from moment to moment. Kierkegaard focuses on the question of what it means to be true, or to exist truthfully.

Hovering in the background here is the famous saying attributed to Jesus by the author of Johns gospel: I am the way, the truth, and the life. If truth can be a way of living, what does this mean for ordinary human beings? This kind of existential truth, or truthfulness, might be conceived in terms of honesty, integrity, sincerity, or authenticity. For Kierkegaard, however, lived truth is primarily a matter of fidelity of being true to another person, or to God, or even to oneself. When truth is understood in this way, the fact that we live in time becomes crucial. Kierkegaard often emphasises that human existence is always in a process of becoming, continually changing and developing to such an extent that no two moments are ever the same. But how can a person who is constantly changing be true, or faithful, to anything?

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How to Believe: Kierkegaards World»

Look at similar books to How to Believe: Kierkegaards World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How to Believe: Kierkegaards World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.