Table of Contents

This book is dedicated to the memory of

GEORGE YULE,

Son and interpreter of the Reformation

and dear friend.

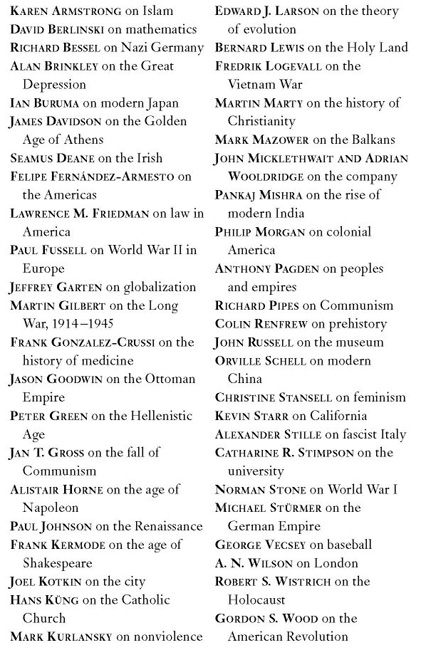

Modern Library Chronicles

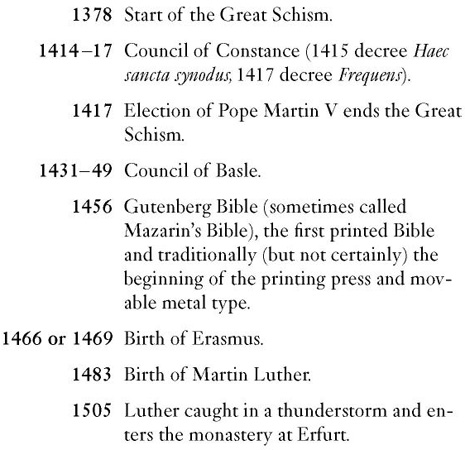

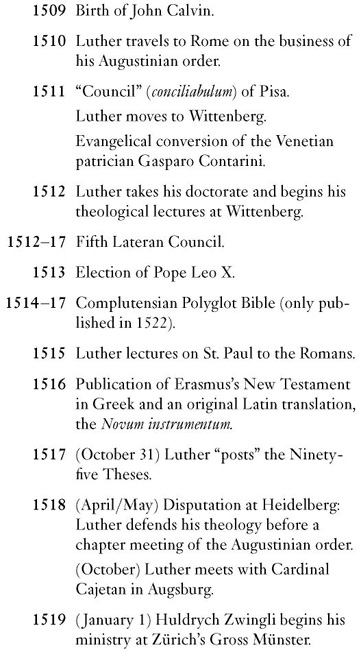

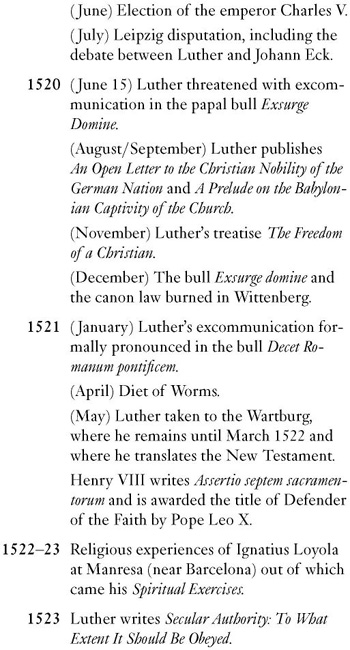

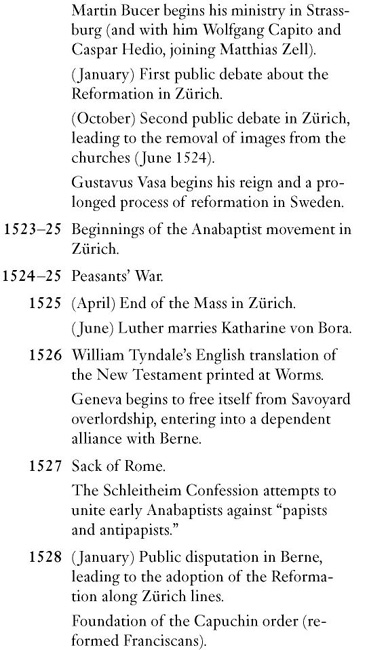

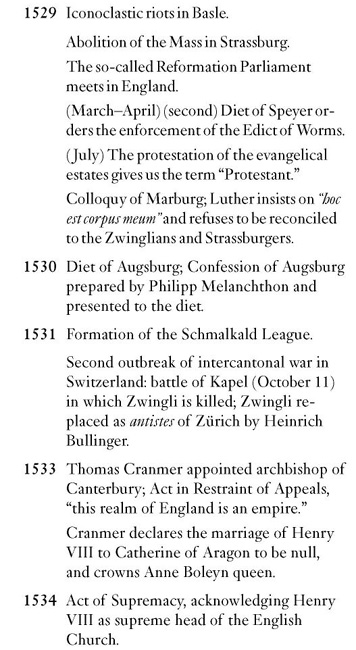

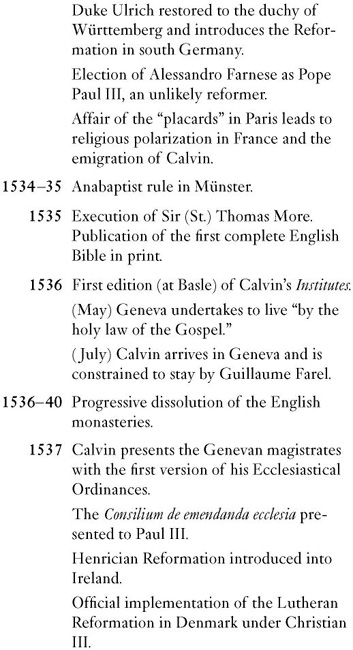

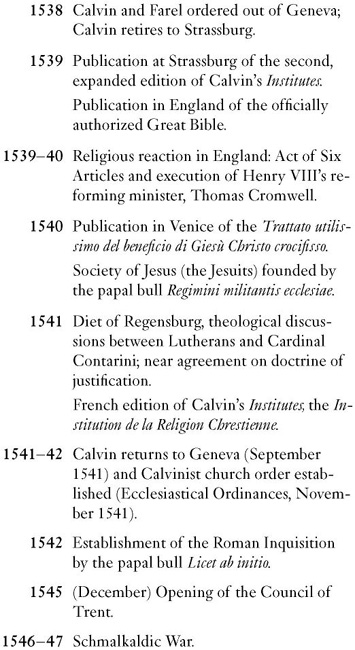

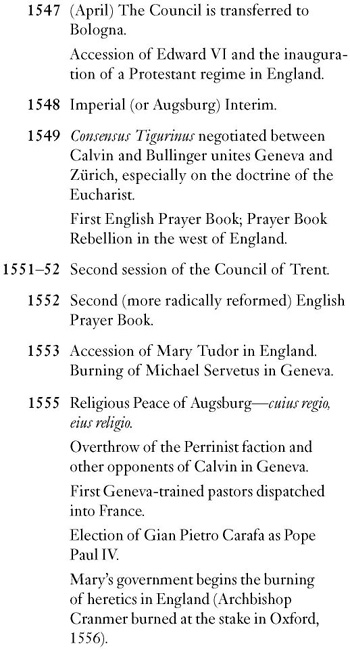

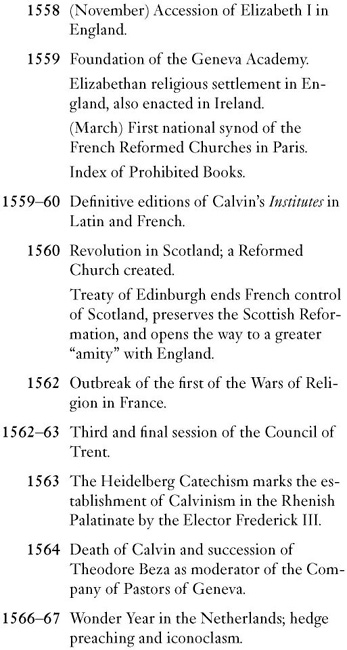

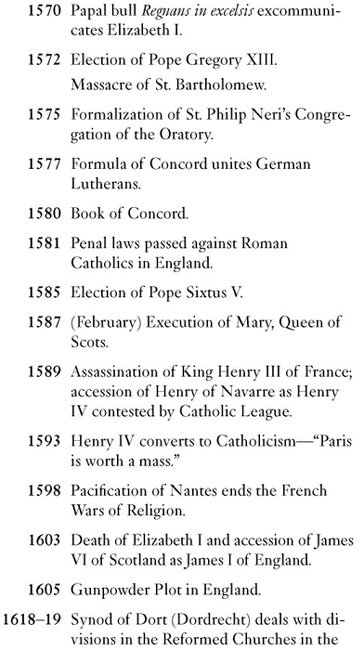

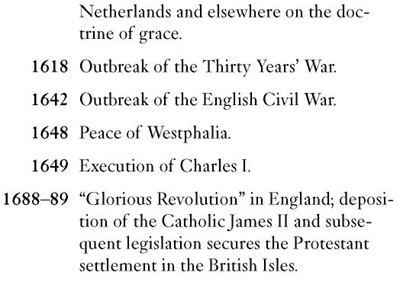

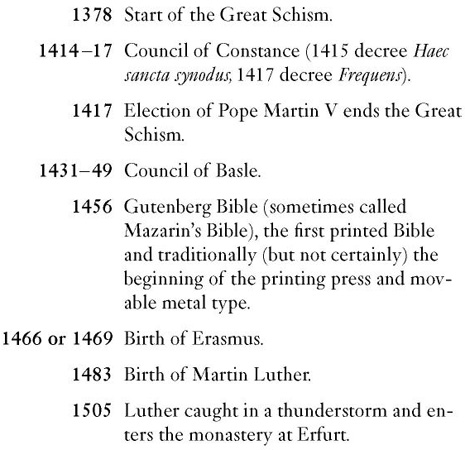

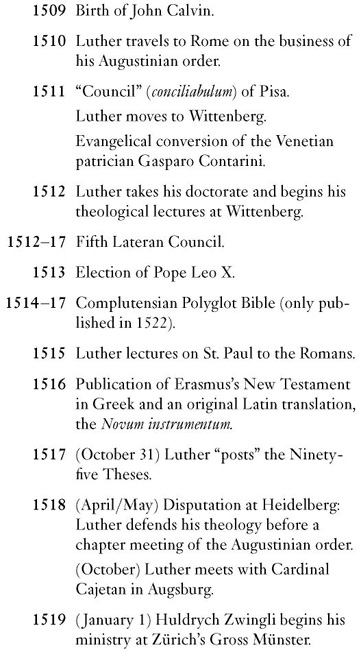

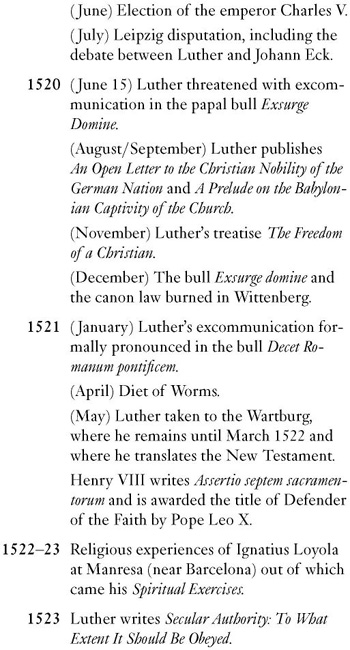

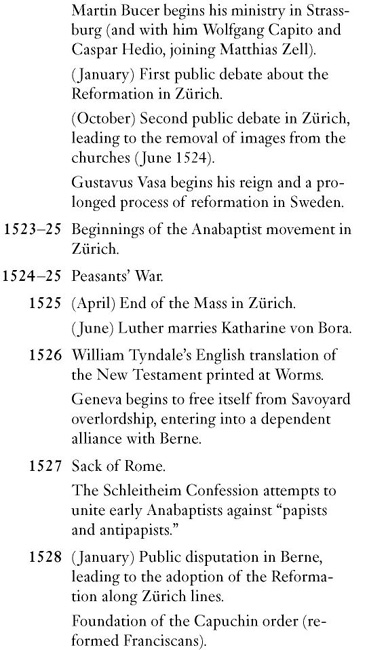

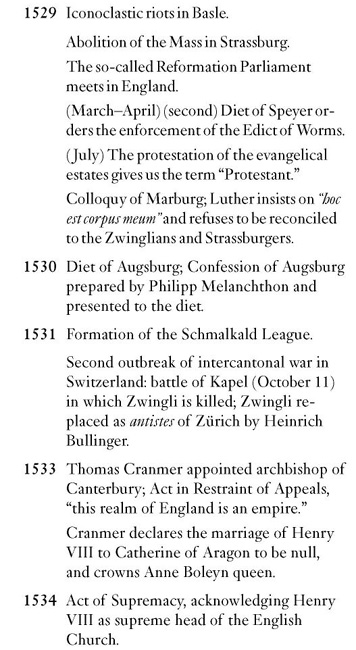

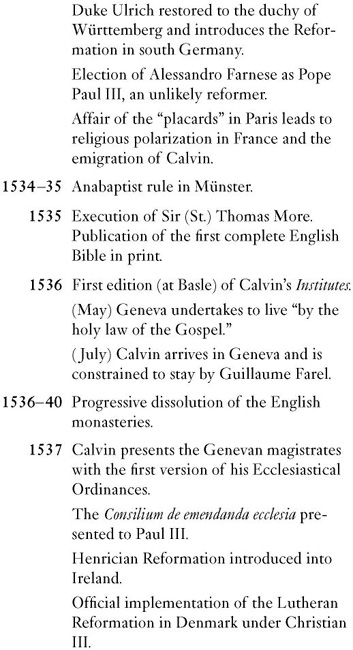

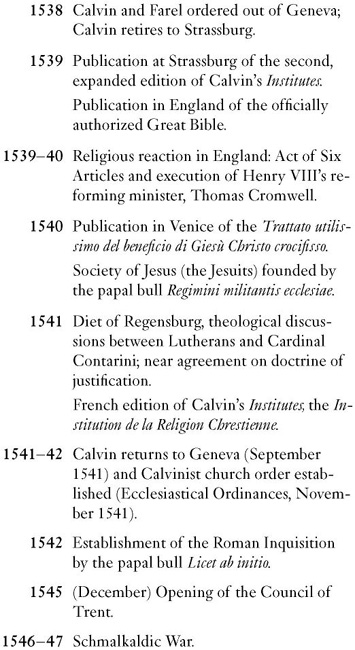

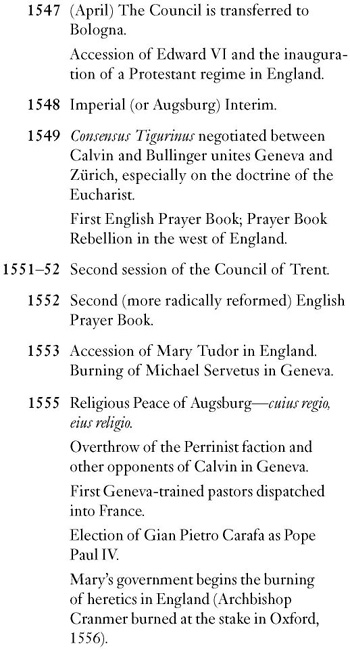

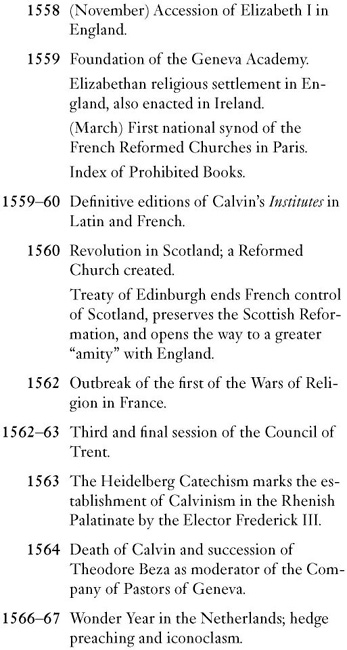

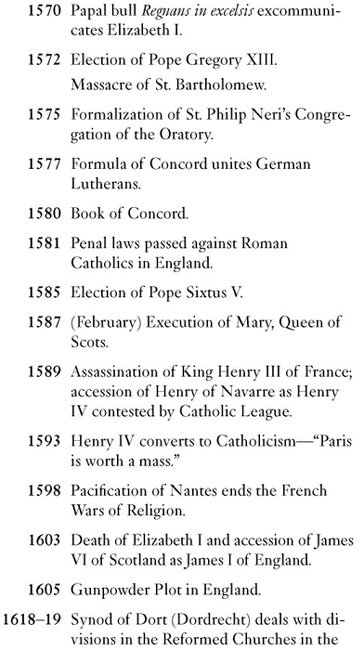

CHRONOLOGY

PREFACE

Between 1961 and 1975, I taught the history of the Reformation, first at Kings College, London, and then at the University of Sydney. In Sydney I delivered more than twenty lectures every year on Martin Luther and related topics. When I added some lectures on the English Reformation, my more perceptive students said, Here is a subject you actually know something about. In the pages that follow, it will be hard to conceal from the intelligent reader my love of Luther and some knowledge of England. Later, at the universities of Kent at Canterbury, Sheffield, and Cambridge, such expertise as I commanded in the history of the Reformation on the Continent became almost redundant. There were accredited European historians to look after the subject and I was reduced to two annual lectures on Lutherin Cambridge, none. In Canterbury, there was Gerhard Benecke, in Sheffield Mark Greengrass, in Cambridge Bob Scribner, the latchets of whose shoes I am not worthy to stoop down and unloose (Mark 1:7).

Bob is no longer here, which is still hard to accept. I want Lois to know that he was looking over my shoulder, I hope not breathing down my neck, as I wrote. We also mourn Heiko Oberman, a great historian of the Reformation and a good man, whose company I shared in Arizona in March 2001 in the very last days of his life, even as I began to think about this little book. Other influences, more implicit than explicit, have been Margaret Aston, John Bossy, Diarmaid MacCulloch, Eamon Duffy, Keith Thomas, and that warmhearted and wonderful Australian George Yule, a dear friend who also departed in 2001, and to whose memory this book is dedicated.

I have never ceased to be interested in the big picture of the Reformation, regretting the provincialism and insularity of English students of the subject (including myself). This little book is a way of paying my respects to a grand historical subject. I hope that those who really know about the Reformation and who have never had to cut corners will not regard it as an insult. Try covering the Reformation, the whole thing, in little more than fifty thousand words! It owes more than I can say to my students on four continentsespecially, thinking of those Australian years, the brothers John and Robert Gascoigne. Nor do I forget A. G. Dickens, my colleague at Kings in the sixties and yet another great Reformation scholar to have died, full of years, in 2001. What a privilege it was to have taught alongside him!

Few of the usual acknowledgments to the helpfulness of archivists and librarians are called for. They have had little to do with this book, which has come out of my head and off my own shelves. Whatever was not there is not here. In this book I have let my hair down and have probably made mistakes too numerous to count. Old men forget. And much will appear dated to those still active at the coalface. My main responsibility has been to the general reader who may know very little about the Reformation, and I have tried my best to make issues that are remote from todays thinking and concerns as accessible as possible. Better to be wrong than to be boring, I always say, but to be neither is best, as several of those named here could have shown me. I am grateful to Eamon Duffy and Mark Greengrass, who read some of the chapters and offered their helpful criticism. Thanks to Eamon, I no longer refer to Luthers performance at the Colloquy of Leipzig as having happened in the hot dog days of 1519. In spite of his verbal diarrhea, there is much that we do not know about Martin Luther, including what may have been his taste in mustard.

TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

November 5, 2002

Remember! remember!

REFORMATION? WHAT REFORMATION?

This is a book about the Christian West: western Christendom, almost equivalent to what would become Europe, the Europe of the EU before enlargement but minus Greece. The western Church, whether obedient or disobedient to that self-appointed successor of St. Peter, the bishop of Rome, has never paid much attention to eastern Christendom, from which it parted company a millennium ago. Whether western Christendom is entitled to think as much of itself as it always has done, not least in investing with a kind of cosmic significance certain events in its history in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, is one of the questions lurking in the background of our investigation of the Reformation.

By comparison with the West, eastern Christendom is not monolithic but rather a family of Churches. Besides those claiming the title Orthodox and acknowledging the honorary primacy of the patriarch of Constantinople as Ecumenical, there were and are other ancient Churches defined both ethnically and by ancient, half-forgotten, but apparently unbridgeable dogmatic differences. They include the Armenians, whose king embraced Christianity and made it the official religion of his kingdom early in the fourth century, a little before Constantine did the same thing for the Roman Empire. Another is the Coptic Church of Egypt, which went its own way doctrinally after the Council of Chalcedon (A.D. 451) defined Orthodoxy, insisting that Christ had only one nature (Monophysitism) and not the Orthodox two, a breach that has so far lasted for fifteen hundred years. Its daughter church in Ethiopia, which since 1959 has called itself the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, is something else, although until 1959 it received its one and only bishop from the Coptic patriarchate of Alexandria. Inseparably identified with the Ethiopian nation, its worship is conducted in an early form of the national languages of that country, and it retains many Jewish features that are perhaps fossils of early Christian practice, such as observance of the Jewish Sabbath and abstention from the forbidden meats of the Old Testament.

Next page