Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

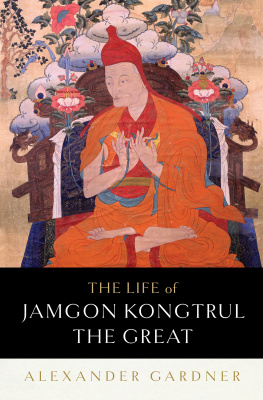

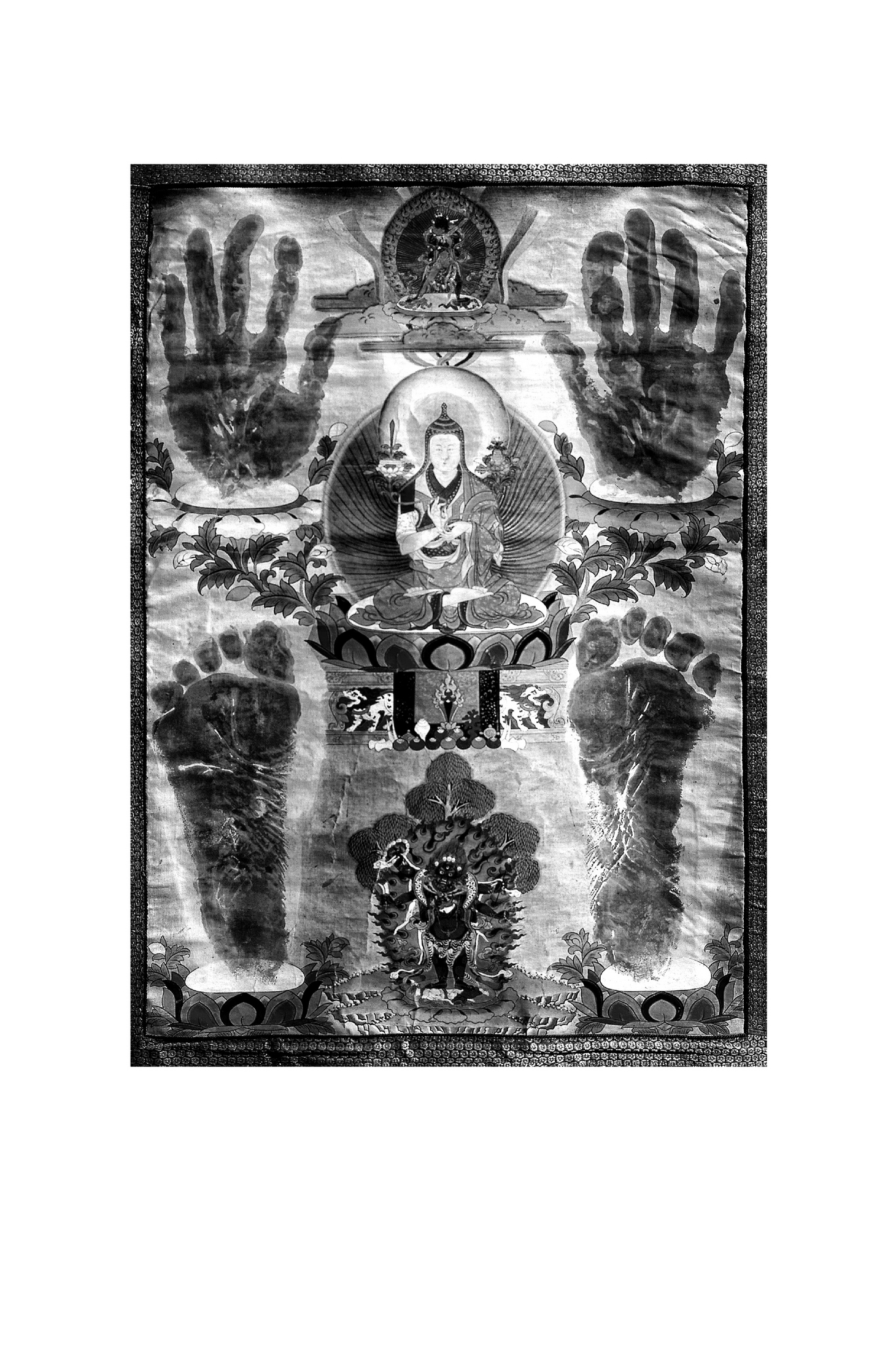

F RONTISPIECE : Painting of Jamgon Kongtrul with hand- and footprints kept in eastern Tibet. Photograph by Matthieu Ricard/Shechen Archives.

Snow Lion

An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2019 by Alexander Gardner

All maps were created by Catherine Tsuji/Treasury of Lives using Mapbox and Open Street Maps.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

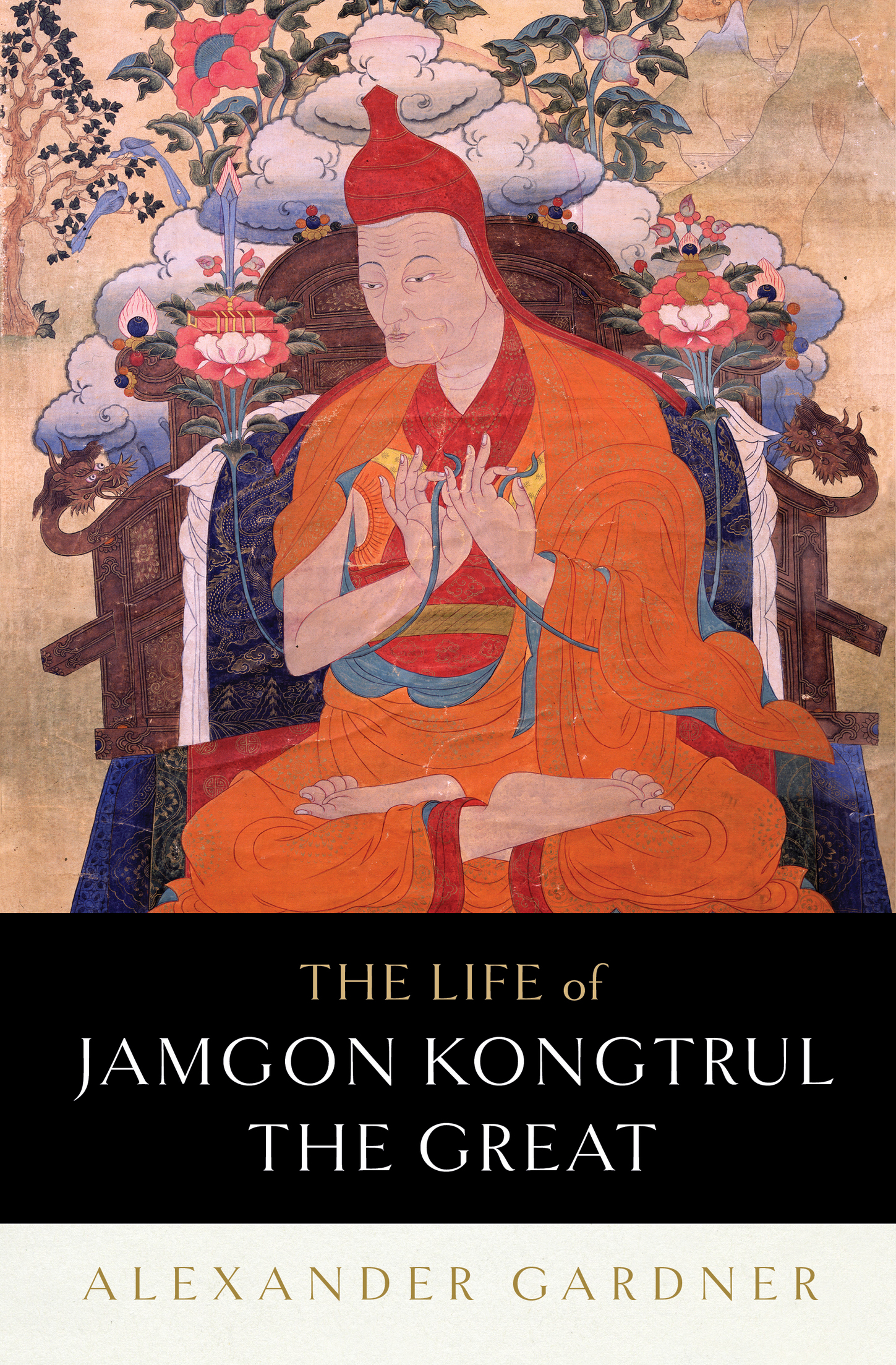

Cover art: Jamgon Kongtrul (detail) Eastern Tibet; Early 20th century Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton Rubin Museum of Art Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin C2006.66.365 (HAR 799)

Cover design: Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING - IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Names: Gardner, Alex (Alexander Patten), author.

Title: The life of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great/Alex Gardner.

Description: First edition. | Boulder: Snow Lion, 2019. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018030207 | ISBN 9781611804218 (hardcover: alk. paper)

eISBN 9780834842090

Subjects: LCSH: Kong-sprul Blo-gros-mtha-yas, 18131899. |

LamasChinaTibet Autonomous RegionBiography. |

BuddhismChinaTibet Autonomous RegionHistory.

Classification: LCC bq968.o57 g37 2019 | DDC 294.3/923092 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018030207

v5.4

a

P REFACE

In the middle of January 1879, an elderly Tibetan monk named Jamgon Kongtrul went on an arduous hike in search of a cave. Kongtrul was then known across the Tibetan Plateau as a collector and propagator of scores of religious traditions, and as a skilled ritual specialist and a man of great learning. The sixty-six-year-old lama and his companion tied rope ladders to rocks, scaled cliffs by clinging to roots and vines, and arrived at a spacious cave high on the central peak of a ridge shaped like a lotus hat. Inside they found a formation which Kongtrul declared to be a naturally arising statue of Padmasambhava, the Precious Guru revered by Tibetans as the man who imbued their landscape with Buddhism. They named nearby overhangs the cave of the religious companion and the long-life cave. Inside these three caves Jamgon Kongtrul found physical evidence of Padmasambhavas long-ago activity therefootprints, small images, and miraculous substances. Pocketing these, he descended the ridge in the midst of a furious wind.

The climb was the culmination of an effort to locate a site that would firmly embed Padmasambhava in a place dear to Jamgon KongtrulRonggyab, the small hidden valley where he was born, a place of undulating flower-strewn meadows and thickly forested slopes. He had spent the majority of his life elsewhere, always moving, walking or riding horses across the region known as Kham. His peregrinations took him from one valley to another, where he would sleep for a night or months at a time in great monasteries, small temples, or cold mountain caves, performing rituals and giving basic Buddhist instruction to increasingly large crowds. He sanctified dozens of placesannouncing the presence of Padmasambhava and other deitiesbuilt monuments and temples, and established ritual programs. He possessed the ability to find the Buddha wherever he placed his feet.

Finding statues and sacred substances in a cave above his home valley was but one moment in the career of a man who spent his life with his feet on the ground, a ground that was rich in miracles and inspirationtreasure in Tibetan parlancebut the ground all the same. For a man who explained profound theories of consciousness and the nature of reality, Jamgon Kongtrul did not live in the abstract. Everything he did was firmly within a tradition, an institution, and most importantly, a place. Jamgon Kongtrul is famous now in Tibet and the West for seeking out a dizzying amount of scripture, publishing it in vast collections, and transmitting it all to future generations of Tibetan Buddhists. His collections of sacred literature, like the retreat schedule he created for his hermitage at Tsdra Rinchen Drak, were nothing less than practical applications of the Buddhas message of nonduality. For Jamgon Kongtrul the scriptures were not so much timeless abstractions as they were lived practices in places where people tended animals and harvested grain. His reverence for the scriptures of Buddhist India was matched by his faith that the Buddhas message of liberation from suffering and compassion for all beings was being revealed in his own landthat the Buddhas teachings were, in fact, always appearing around him. Kongtrul did all of this with an ecumenical attitude and heartfelt appreciation for the diversity of Tibetan doctrinal and ritual systemsthe extent of which has rarely been seen elsewhere.

Western scholars and devotees fill libraries with biographies of Christian and Jewish saints and religious leaders. The best of these accounts tell the story of the life of such individuals in a way that shows their inspiration while allowing for the lived reality of the person, their struggles, and their humanity to shine through. The worst depict the subject as perfectly formed at birth, untainted by the concerns of the communities around them. After over a hundred years of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies in the West, biographies of Tibetans in English and other European languages continue to treat their subjects less as people and more as archetypes. This book is the first full-length biography of Jamgon Kongtrul written in English, and it joins a mere handful of historical biographies of Tibetans, chief among them David Jacksons biography of the Third Dezhung Rinpoche and Donald Lopezs biography of Gendun Chopel. I hope this book will not be the last word on Kongtrul, as there are many unanswered questions and many fascinating issues about his life left to be explored. A literary biography, which surveys his compositions and traces the development of his thinking, would be a great contribution. We still await full biographies of his key collaborators, Khyentse Wangpo and Chokgyur Lingpa, who both feature prominently in this book.

Jamgon Kongtrul kept a detailed diary that was published in Tibetan and translated into English in 2003 by Richard Barron. It is a fascinating first-person account of his activities, and I encourage readers to consult it. It serves as the primary source for this book, but I do not approach it uncritically. Barron gave his translation the title The Autobiography of Jamgon Kongtrul, but the work is almost entirely a record of events rather than a fully crafted autobiography. Outside of the section of his youth, there is little sense of narrative arc. Still, Kongtrul was, like most people, concerned about how his peers and posterity would view him, and he edited and framed his narrative accordingly. Kongtrul was perpetually creating, producing, and redefining, even if he was forced by social convention and literary norms to present himself as a passive receiver of commands, advice, and the fully crafted works of others. He could not acknowledge his active role in his own endeavors without risking accusations of egotism, and so he credits the inspiration or command for almost everything he did to his colleagues. He made inevitable errors, occasionally inserting information at points in the work that is anachronistic, misleading, or simply confused.