Also by WILLIAM FARINA

AND FROM MCFARLAND

The Afterlife of Adam Smith: The Influence, Interpretation and Misinterpretation of His Economic Philosophy, 1760s2010s (2015)

Man Writes Dog: Canine Themes in Literature, Law and Folklore (2014)

The German Cabaret Legacy in American Popular Music (2013)

Eliot Asinof and the Truth of the Game: A Critical Study of the Baseball Writings (2012)

Chrtien de Troyes and the Dawn of Arthurian Romance (2010)

Perpetua of Carthage: Portrait of a Third-Century Martyr (2009)

Ulysses S. Grant, 18611864: His Rise from Obscurity to Military Greatness (2007)

De Vere as Shakespeare: An Oxfordian Reading of the Canon (2006)

Saint James the Greater in History, Art and Culture

WILLIAM FARINA

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3281-0

2018 William Farina. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

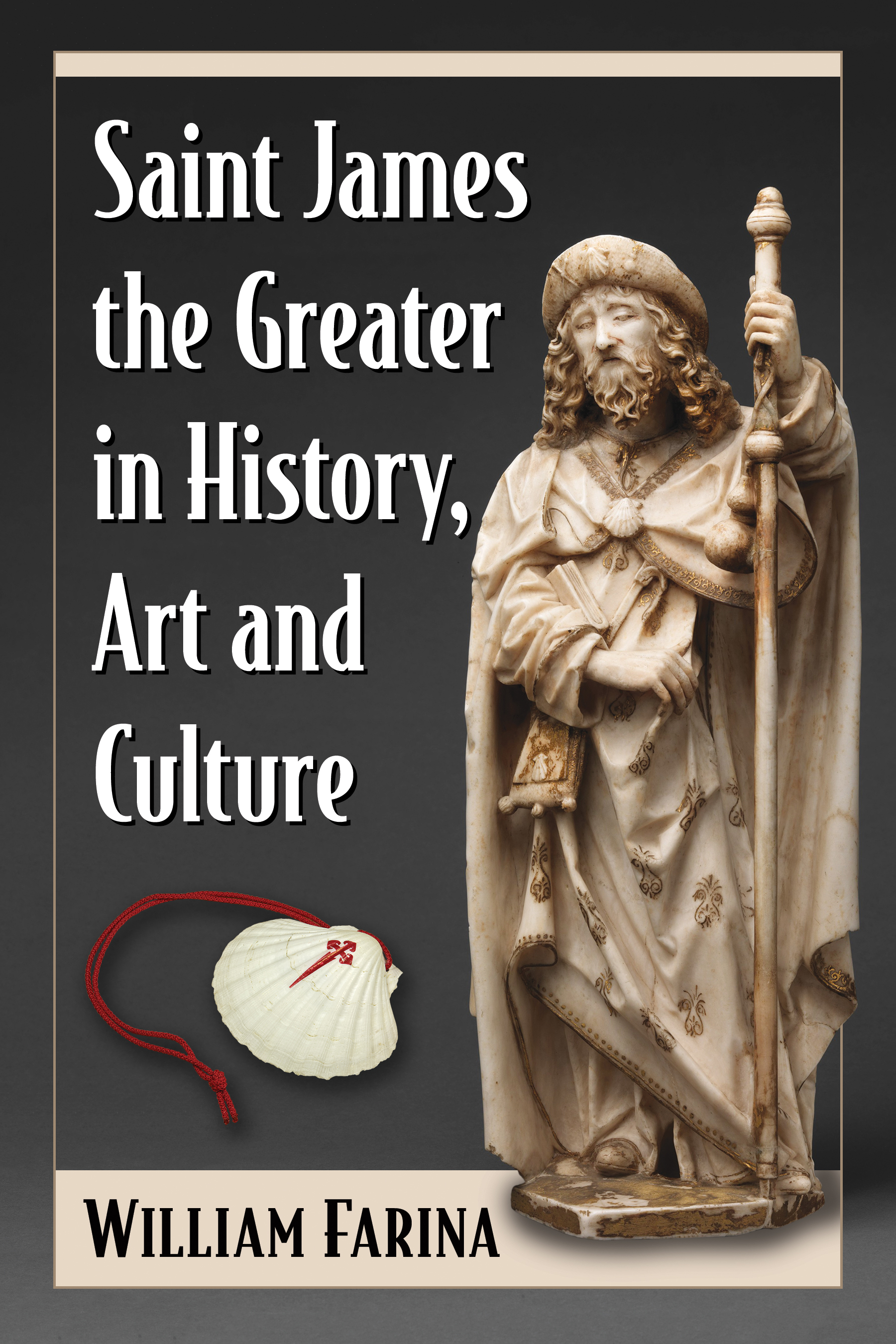

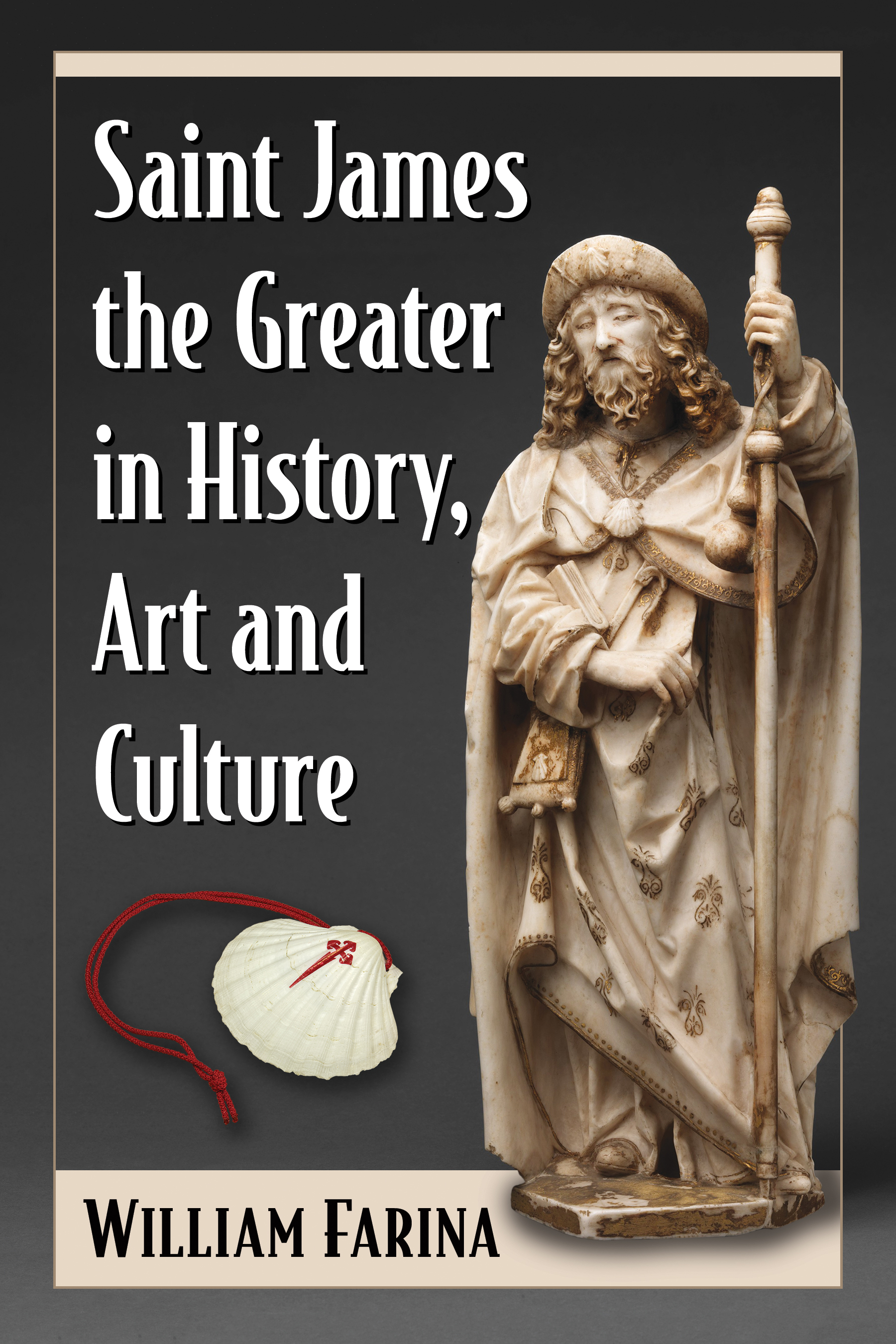

Front cover: statue of Saint James the Greater by Gilde Siloe (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection); Pilgram Shell photograph 2018 PFMphotostock/iStock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the memory of

recently deceased friends

and loved ones

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my life companion Marion Buckley for patiently listening to book thoughts randomly spoken aloudyou are still my most valuable audience. Thanks to my brother Joseph Farina for contributing his considerable storehouse of knowledge on the visual arts. Repeated thanks to Philip and Kathleen Farina for always being enthusiastically engaged; thanks to Greg Jorjorian and Marlys Conrad for introducing me to the epic heritage of Armenian Christianity.

Thanks to Mimi Herrington and James Warshall for offering a librarians perspective, helpful observations on C.S. Lewis, and lending me their dining room table. Thanks to Dr. Robert Orsi and Dr. Christine Helmer for being good role models, and to Steven and Ethel Rosenberg for their non-stop flow of wit combined with common sense. And thanks again to the libraries at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago, as well as their patiently supportive staff.

Last but far from least, special thanks to my friend, the late Rev. Dr. Robert Cotton Fite (19382017), for his boundless encouragement and good cheer in times most needed.

Introduction

Of these holy romances, that of the apostle St. James can alone, by its single extravagance, deserve to be mentioned. From a peaceful fisherman of the lake of Gennesareth, he was transformed into a valorous knight, who charged at the head of the Spanish chivalry in their battles against the Moors.Edward Gibbon

Some years past while flying from Paris to Chicago one beautiful morning, I looked out of the passenger window to gaze upon some of the most spectacular landscape ever beheld during my travels. It was the Green Spain of Asturias, the northern Iberian coastline facing the Bay of Biscay. Previously, my mental image of Spain had been strictly one of arid, dry countryside dotted by patches of vineyards, olive groves, and a few scattered, dense urban oases. It occurred to me that Spain and the Iberian Peninsula have their own venerable traditions in this regard, some of which appear to have originated in the very same region then being flown across. Moreover, a strong case could be made that these Iberian traditions have contributed towards more tangible, permanent results in terms of worldly affairs, than any of their trans-European counterparts. In any event, the experience has stayed with me, and these pages represent one outcome of that strong first impression.

Historians normally apply the term Reconquista to the long period spanning roughly from 711 CE to 1492 in which Christian Spain and Portugal slowly recovered from the Islamic conquest of the early eighth century, gradually reclaiming the Iberian Peninsula while invoking the Roman Catholic faith. Among Anglo-Americans, this tremendous achievement too often represents barely a footnote for the preColumbian era in Europe, but to the rest of the world (including countless displaced Muslims and Jews) it was and remains a big deal, the profound significance of which is unlikely to change anytime soon. Near the beginning of the process, however, the famed cult of Saint James the Greater or Santiago Mayor, surnamed Matamoros (Moor-slayer), physically centered at Santiago de Compostela in the Galician province of far northwestern Spain, took momentous hold. Today, Christians and nonChristians alike continue to make arduous pilgrimages on foot or otherwise to Santiago de Compostela, for which they are presented with official certificates of completion from the Vatican.

After 1492, this strident and fanatical militarism took on an entirely new dimension, but continued to use Saint James the Greater as its symbolic figurehead. Within the astonishingly short time frame of five decades, two heavily populated continents had been discovered and largely subjugatednot unlike the manner Umayyad invaders had overrun the Iberian Peninsula within a matter of months during the eighth century. Spanish and Portuguese conquest of the New World, by contrast, involved a much larger geographic area of hitherto unknown territory, with far more global and lasting impact on religion, language, and culture. Admittedly, the permanent Islamic influence on Spain and Portugal had been significant and far-reaching as well; indeed, some of this Islamic influence, particularly via art and architecture, carried over into the New World in the immediate wake of Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores. By comparison to the overt legacy of the Santiago cult, however, the subtle sway of Moorish culture on the New World must be viewed as less pronounced.

Today, longstanding traditions of Saint James the Greater continue to spark imaginations for those engaged in less warlike and more spiritual quests of the heart and mind. Military conquest has, for the most part, been supplanted by personal inward journeys. The European Renaissance only seemed to heighten this veneration, producing a magnificent body of visual art by many of its greatest masters. Even after the Reformation had blunted the global authority of Roman Catholicism, writers such as Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Montaigne (among many others) all were making casual literary references to Saint James the Greater as warrior-knight, pilgrim wayfarer, or both. Today, the shrine of Galician Santiago continues to present itself as a physical thread of spiritual continuity over the last 13 centuries, fully justifying its current designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is commonly and accurately observed that the traditional burial site of Saint James the Greater in Spain continues to be the most popular religious destination in Christendom after Rome and the Holy Land.

While the end of the 16th century saw Anglo, French, and Dutch interests effectively block further Spanish-Portuguese expansion into North America, the latter two (by then temporarily combined into a single political entity) had auspiciously begun its close assimilation into Native American societies as well. After this they would only be removed by force and rather infrequently at that. The remaining political question would be to what extent these newly evolved societies would govern themselves autonomously or be ruled remotely by distant powers. The national emergence of the United States during the late 1700s and Latin American national independence movements immediately following in its wake both decisively answered these questions, although political relations within these the two blocs continues to evolve in a complex and unpredictable manner. Curiously, veneration for Saint James the Greater continues to be seen everywhere, even among those whose religious beliefs may be described as marginally Christian at best. One might well argue that, for Latin Americans and their Native American religious converts, a new

Next page