Why is it, I wonder, that anyone who displays superior athletic ability is an object of admiration to his classmates, while one who displays superior mental ability is an object of hatred?

The age of the pulp magazine was the last in which youngsters were forced to be literate. True literacy is becoming an arcane art, and the nation is steadily dumbing down.

Ill never talk myself into trying a flight. Whats more, there is always the extraordinary publicity and macabre detail with which every airplane crash is greeted, and with each grisly incident, my firm intention never to fly is strengthened.

How does one become a really prolific writer? The very first requirement is that a person have a passion for the process of writing. I mean he must have a passion for what goes on between the thinking of a book and its completion.

If I were not an atheist, I would believe in a God who would choose to save people on the basis of the totality of their lives and not the pattern of their words. I think he would prefer an honest and righteous atheist to a TV preacher whose every word is God, God, God, and whose every deed is foul, foul, foul.

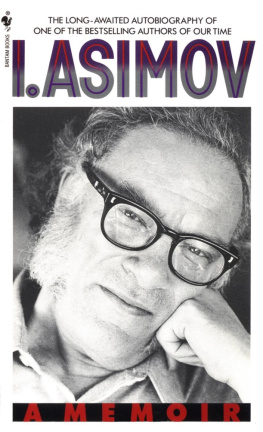

Introduction

In 1977, I wrote my autobiography. Since I was dealing with my favorite subject, I wrote at length and I ended with 640,000 words. Since Doubleday is always overwhelmingly kind to me, they published it allbut in two volumes. The first was In Memory Yet Green (1979), the second In Joy Still Felt (1980). Together, they described the first fifty-seven years of my life in considerable detail.

It had been a quiet life and there was no great excitement in it, so even though I made up for that by what I considered a charming literary style (I never bother with false modesty, as you will quickly discover), the publication was not a world-shaking event. However, some thousands of people found pleasure in reading it, and I am periodically asked if I will continue the tale.

My answer always is: I have to live it first.

It was my notion that I ought to wait till the symbolic year of 2000 (always so important to science fiction writers and futurists) and write it then. However, I will be eighty years old in 2000 and it may just be possible that I may not make it till then.

When, just before my seventieth birthday, I was stricken with a rather serious illness, my dear wife, Janet, said to me severely, Start that third volume now.

I protested feebly and said that the last twelve years had seen my life turn quieter than ever. What could I possibly have to say? She pointed out that the first two volumes of my autobiography were strictly chronological. I recounted events in precise order according to the calendar (thanks to a diary Ive kept since I turned eighteen, to say nothing of an excellent memory) and I had said almost nothing about my inner being. She said she wanted something else for the third volume. She wanted a retrospective in which the events were secondary to my thoughts, my reactions, my philosophy of life, and so on.

I said, even more feebly, Who would be interested?

And she said firmly, for she is even less falsely modest on my behalf than I am on my own, Everybody!

I dont think shes right, but she might be, so I intend to try. I dont intend to start where the second volume left off. In fact, it would be dangerous to do so. The first two volumes are out of print and many people who might pick up this volume and find it interesting (stranger things have happened) would be unable to find the first two volumes in either the hard- or soft-cover incarnation and grow seriously annoyed with me.

So what I intend to do is describe my whole life as a way of presenting my thoughts and make it an independent autobiography standing on its own feet. I wont go into the kind of detail I went into in the first two volumes. What I intend to do is to break the book into numerous sections, each dealing with some different phase of my life or some different person who affected me, and follow it as far as necessaryto the very present, if need be.

I trust and hope that, in this way, you will get to know me really well, and, who knows, you may even get to like me. I would like that.

1

Infant Prodigy?

I was born in Russia on January 2, 1920, but my parents emigrated to the United States, arriving on February 23, 1923. That means I have been an American by surroundings (and, five years later, in September 1928, by citizenship) since I was three years old.

I remember virtually nothing of my early years in Russia; I cannot speak Russian; I am not familiar (beyond what any intelligent American would be) with Russian culture. I am completely and entirely American by upbringing and feeling.

But if I now try to discuss myself at the age of three and the years immediately beyond, which I do remember, I am going to have to make statements of the type that have always led some people to accuse me of being egotistical, or vain, or conceited. Or, if they are more dramatic, they say I have an ego the size of the Empire State Building.

What can I do? The statements I make certainly seem to make it clear that I think highly of myself, but only for qualities that, in my opinion, deserve admiration. I also have many shortcomings and faults and I admit them freely, but no one seems to notice that.

In any case, when I say something that sounds vain, I assure you it is true and I refuse to accept the accusation of vanity until somebody can prove that something I say that sounds vain is not true.

So I will take a deep breath and say that I was an infant prodigy.

I dont know that there is a good definition of an infant prodigy. The Oxford English Dictionary describes it as a child of precocious genius. But how precocious? How much genius?

You hear of children who can read at two, who learn Latin at four, who enter Harvard at the age of twelve. I suppose those are undoubted infant prodigies, and, in that case, I was not one.

I suppose that if I had had a father who was an American intellectual, well off and lost in his study of the classics or of science, and if that father had discovered in me a likely candidate for prodigiousness, he might have driven me onward and gotten something like that out of me. I can only thank whatever chance has guided my life that this was not so.

A force-fed child, driven relentlessly to the very top of his bent, might break under the strain. My father, however, was a small storekeeper, with no knowledge of American culture, with no time to guide me in any way, and no ability to do so even if he had the time. All he could do was to urge me to get good marks in school, and that was something I had every intention of doing anyhow.

In other words, circumstances conspired to allow me to find my own happy level, which turned out to be sufficiently prodigious for all purposes and yet kept the pressure at a sufficiently reasonable value to allow me to chug along rapidly with no feeling of strain whatever. It meant that I kept my prodigiousness for all my life, in one way or another.