Part I. LEARNING TO TAKE CHARGE OF YOUR OWN NARRATIVE

Part II. LEARNING TO ASK

Part III. LEARNING TO SAY NO

Part IV. LEARNING RESILIENCE

Courtney E. Martin

J. Courtney Sullivan

Carol S. Dweck

I NTRODUCTION

P lease talk about a mistake youve made in your career and what you learned from it, said the panel moderator from the brightly lit stage. The audience of college students and professors emitted a low hum of anticipation.

I grabbed a pen, eager to hear what the five successful women sitting in front of me had to say. The topic was of personal interest to me, particularly given my recent change in career. It had been a risk for me to accept my role as inaugural director of Smith Colleges Wurtele Center for Work and Life, a challenge that I relished but that made me nervous. Although I wanted to do nothing wrong, chances to mess up were everywhere. Managing a budget, I overdelegated to a new assistant and ended up with a shortfall. Developing new leadership programs, I stepped on toes. I made errors on publicity materials, accidentally printing the wrong title for Julianna Smoot, who has held several high-level roles in the Obama administration. Although she was gracious about it, I was mortified. For these and other blunders, I would spend days feeling like an imposter in my new role. Did others feel the same way? Did these women ever make such blunders?

Sitting in the panel audience with my notebook open, I wanted to hear something that would make me feel less alone, to fill a page with other peoples stories. But after twenty minutes, that page was still blankand oddly, this wasnt the first time Id encountered such hesitation, or even avoidance, when it came to discussing errors on the job. For instance, my boss sent me to a leadership training week where several high-level women extolled the virtues of mistakes without talking about their own. Another time, I joined some students to hear from a notable visitor who generalized about her sacrifices and trade-offs, never saying what they were.

To be fair, you could say these women were just putting their best foot forward and that its difficult to talk about mistakes in a high-pressure situation. But over the years, Id seen too many women waxing rhapsodic about the value of learning from mistakes without actually describing any, to find that platitude helpful. It was advice served, like mediocre breakfast pastries, at just about every professional conference. The average woman (like myself) hears it and thinks, Sure, easy for you to say its important to learn from mistakes, but your mistakes arent like mine. Mine are huge. After all, if those whove made it ever really did anything wrong, they wouldnt be where they are nowright?

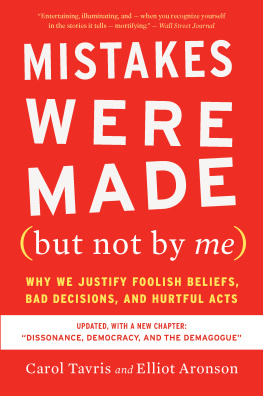

When I hear the imperative to learn from your mistakes, I also hear echoes of the good girl messaging that permeates our culture. Starting in elementary school, girls feel pressure to be perfect, accomplished, thin, and accommodating, according to a 2006 Girls Inc. report. This sounds exhaustingand it can also be damaging, keeping girls from stepping outside of their comfort zones. In 2007, psychologist Carol Dweck and her colleagues found that when learning new material, bright girls did not cope well with confusion. In fact, the higher the girls IQ, the worse she did. Girls were more likely than boys to become demoralized by a challenge, as if it called their ability into question. The pressure that those girls felt to have it together often follows young women to college and beyond. A well-known study at Duke University found that female students experienced a mandate of effortless perfection. A 2013 New York Times article about Harvard Business School reported that women there participated in class less than men becauseaccording to faculty and administratorsthey often felt they had to choose between academic and social success. Its as if even these high-powered go-getters didnt want to risk seeming too aggressive or giving a wrong answer. Clearly from girlhood through graduate school, we are absorbing unhelpful messages about the many ways in which were supposed to do things rightand vague advice about learning from mistakes can blur unhelpfully into all of that.

But what if we heard stories about doing things wrong? I have witnessed the effects firsthand. After bestselling author Rachel Simmons gave a speech at Smith College about dropping out of Oxford, students, transfixed, didnt want to leave the hall. During a panel on failure, I saw looks of happy surprise come over students faces when a faculty member talked about a paper that hadnt been accepted in a prestigious journal. The young women I worked with expressed relief when people they admired opened up about their own setbacks and mistakes; in fact, they seemed to respect these people for feeling comfortable sharing narratives that werent just success stories but were instead laced with emotions like anxiety, frustration, and shame.

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA