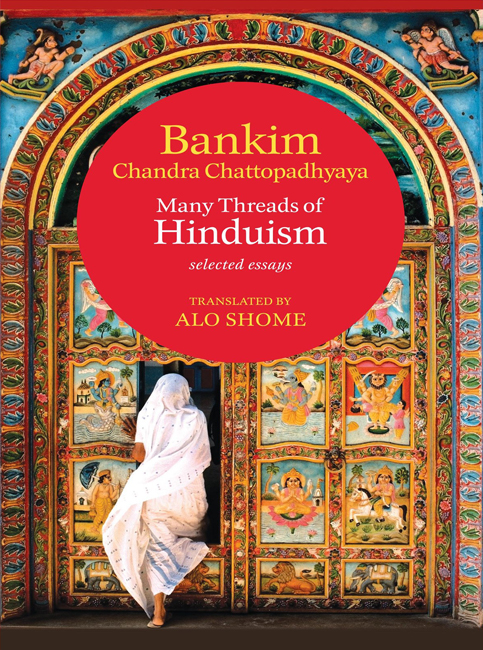

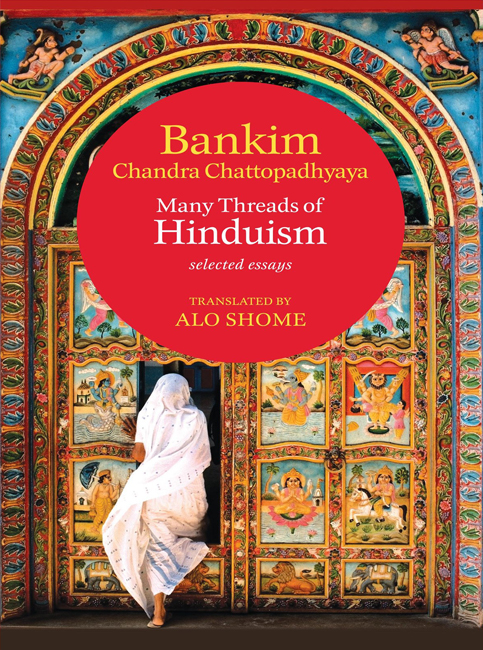

MANY THREADS OF

HINDUISM

Selected Essays

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya

Translated by Alo Shome

This book is for Amalina and Nivedita

Contents

The opinions expressed in this collection of essays are the opinions of Sri Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya. The translator does not take any credit for the interpretations recorded in this volume.

The translators own comments on various issues appear only in the footnotes and translators notes.

B ankim Chandra was born in Kanthalapara, near Kolkata, on 26 June 1838. He was the second of three sons of Durgasundari Devi and Jadav Chandra Chattopadhyaya, a senior government officer.

After an English-medium education in a Medinipur convent school and six years in Mohsin College, Hooghly, Bankim joined Presidency College, Kolkata, and prepared for his BA examination. In 1858, along with Jadunath Basu, he was one of the first two candidates to graduate from Calcutta University.

After his studies, Bankim Chandra served the government as a hard-working deputy collector and deputy magistrate. His British superiors acknowledged his proficiency in work and the uprightness of his character in spite of their differences of opinion with him on several matters. Bankim was even honoured with the titles of Rai Bahadur in 1891 and Companion of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire (CMEOIE), in 1894.

Bankim had to marry a five-year-old girl when he was eleven years old to oblige his elders who believed in the deplorable Hindu custom of child marriage. However, this marriage lasted only about ten years, as the bride died at a tender age. Bankims second marriage with Rajlakshmi Devi was happy and fulfilling. They had three daughters. Unfortunately, the youngest of them committed suicide a few years after her wedding.

Bankims first novel, Rajmohans Wife (1864), was written in English. His first Bengali novel, Durgesh Nandini, was published in 1865. Some of his other masterpieces are Kapal Kundala, Mrinalini, Devi Chaudhurani and Ananda Math. Including Rajmohans Wife, he wrote sixteen novels. He also composed poems, most of them at a young age.

Besides being an outstanding novelist and a poet, Bankim Chandra was a prominent intellectual of his time who contributed thought-provoking articles to various newspapers and magazines, some of which he edited for many years. His work covered various subjects including politics, economics, social sciences, religion, philosophy and popular science. Religion was one of his main areas of interest.

Bankim sensed that India had become divided between the traditionalist orthodox, who were slaves to rigid customs, and the contemporary reformers, who were blindly emulating the West. He believed that both were at fault. To his mind the best choice for India was to draw its inspirations selectively and cautiously from both the traditions.

An incident in 1882 drew Bankims attention towards religious studies. A Scottish missionary, Reverend William Hastie, took to publishing a series of articles in The Statesman criticizing Hinduism. Bankim had something to say about these censures and his objections to them appeared in the same newspaper. However, Bankim had used a pseudonym Ramachandra. This brilliant give-and-take the debate between the missionary and Bankim earned much popularity for the paper at that time.

Bankim never ceased to inspire and encourage young authors. He had an eye for talent. When an inexperienced Rabindranath Tagore, at the age of twenty-two, published his first novel, Bou Thakuranir Haat (1883), he unexpectedly received a letter of praise, written in English, from Bankim Chandra.

In 1891, Bankim took voluntary retirement from government service and devoted the rest of his life mainly to the study of religious subjects. He died on 8 April 1894 at the age of fifty-six.

B ankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya has written extensively on Hinduism, especially from 1870 until his death in 1894. Appreciating his works on religion, Aurobindo Ghose called him a rishi. Nirad C. Chaudhuri believed that Bankim had one of the greatest Hindu minds, perhaps equalled in the past whole of the Hindu past only by the great Samkara.

Bankim has not given any specific definition of Hinduism. Instead, he begins by analysing what religion means to the people who call themselves Hindus. This he does, perhaps, intentionally because Hinduism, unlike the names of other religions, is a vague term. In ancient India there was no religion called Hinduism and there is no reference to the word Hindu in any Vedic scripture. The nouns India and Hindu have the same etymological past but do not mean the same thing in todays world. Both the words India and Hindu originate from the name of River Sindhu. The ancient Persians could not pronounce the letter S and so called the river and the people living on its banks Hindu. The Zend-Avesta refers to the word Hindu only as a geographical expression. The ancient Greeks called the same river the Indus and the land next to it, India.

Bankim Chandra harboured some animosity for European people the colonizers who dominated India in his lifetime and sometimes made angry remarks about them in his writings. However, that did not stop him from sincerely respecting the Western intellectual tradition. Like many prominent Indians of his time, he was deeply and fruitfully influenced by Western thoughts. A well-rounded English education had made him realize the tremendous value of research and analytical work in discovering the truth in any matter. And he applied his energies in a meticulously scientific manner to find out the real significance of his personal religion and culture. His findings led him to believe that Hinduism had enough to give to its followers and the world, if people were ready to respond to its messages with an open mind. At the same time, he was not blind to its faults and limitations.

Unlike many Hindus, Bankim did not have blind faith in the infallibility or agelessness of the Vedas. In this matter his assessment coincides with Dr S. Radhakrishnan who wrote, The Vedas are neither infallible nor all-inclusive. Spiritual truth is a far greater thing than the scriptures. Bankim Chandra had jokingly commented that the hold of the Vedas upon the Hindus was much stronger than the hold of the British rulers upon them. He did not believe that mantras had any mystic powers and regretted the abundance of rituals in the Vedic religion.

From beneath the ashes of myths, legends, superstitions, exaggerations and rituals that had lost their contexts, he laboured to restore the quintessential truth of Hinduism piece by piece. His was the delicate work of an archaeologist passionately recovering valuable artefacts.

Methodology

Bankim Chandra has often used the first person plural we as the speaker in his essays on religion. In reality, barring exceptional cases, they express his very own personal thoughts based on his individual research. Bankim Chandras use of we instead of I is a way for him to represent the journals in which his essays appeared. His studied approaches to Hinduism were published regularly in the Bengali magazines Navajeevan, Prachar and Banga Darshan in the 1880s. Often, the major portions of these journals consisted of Bankims own writings. I, the translator, have generally used the first person singular to represent Bankim.

This is a selective translation of Bankims articles on religion. Sometimes a whole article has been translated while in other cases a portion of an essay has been done. This has occasionally demanded some adjustments to the original titles of the articles.

Next page