NEW ZEALANDS LONDON

A Colony and its Metropolis

FELICITY BARNES

CONTENTS

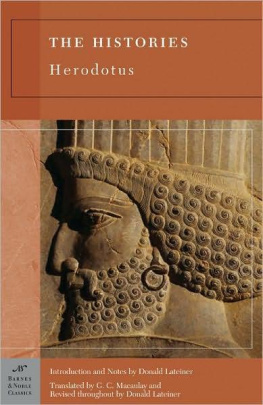

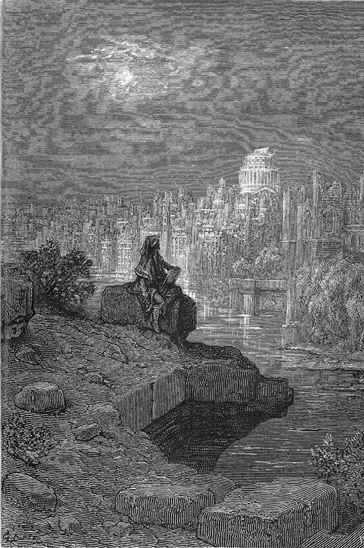

The New Zealander by Gustave Dor. Gustave Dor and Blanchard Jerrold, London: A Pilgrimage, reprinted New York, 1970, n.p.

INTRODUCTION

I N 1840, THE SAME YEAR that New Zealand was formally incorporated into the British Empire, a mysterious New Zealander appeared in Londons metaphorical landscape. In a review of a history of Catholicism, Thomas Macaulay invoked the image of some traveller from New Zealand (in 1840, this meant a Maori traveller) who, at some undetermined time in the future, might in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand upon a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St Pauls.

The fictive New Zealander on London Bridge was one more expression worn through in the process of creating the metropole as civilised centre. Colonial peripheries and their peoples commonly served as

And there, fixed as a phantom form of otherness, the New Zealander might have stayed. Yet by the turn of the century, a strange shift in this convention was occurring. New Zealanders could still be found on London Bridge, but they were not symbols of otherness anymore. Instead, they took physical, not phantom, form as Britons at home in their imperial metropolis. Furthermore, they had left New Zealand, former symbol par excellence of a distant time, so that they might discover their heritage by returning to London and England. New Zealand took on a new shape in the metropolis. It was no longer part of the past: old, colonial New Zealand, with its Maori, myths and pioneering migrants, was metamorphosing into a dominion, a new and modern member of empire. Space was changing too: London, home city of empire, became a joint New Zealand possession and, by way of exchange, New Zealand considered itself to be a farming hinterland of the metropolis, and a distant colony no longer.

London, then the biggest city in the world, had become New Zealands cultural capital. But this was no cringing colonialism. It was cultural co-ownership. The Britons on the bridge claimed Londons streets as their streets, and its history as their heritage too. New Zealands literature was published there, and its news was collected in Fleet Street. New Zealands butter, meat and cheese filled the windows of London chain stores, and New Zealands school children were quizzed on the best routes to send these products there. Visitors from New Zealand did not beg for invitations to royal garden parties; they went to New Zealand House to demand Even in the twenty-first century, New Zealanders can still use London as if it were an extension of New Zealand.

This long attachment to London has become a familiar part of New Zealand culture, so natural that it has never been examined. If asked to explain it, we might see the relationship as an outcome of New Zealands settler past, as a quaintly sentimental colonial habit or as a faintly embarrassing echo of empire. However, as reasonable as these explanations appear, none of them is entirely accurate. The cultural relationship between London and New Zealand was, of course, a product of the colonial past. But as the statistics for visas suggest, ties of kinship only partially explain Londons attractiveness to New Zealanders. Having a direct connection with London was less important than imagining such a connection, and, from around the end of the nineteenth century, that was easy to do. From that time, new communication technologies began working to draw the former colony and metropolis closer together. In books and in newspapers, in films and eventually on television, London was a constant presence. When children got out their Monopoly sets, they fought over who owned Londons Park Lane and Mayfair, not Atlantic Citys Park Place and the Boardwalk. Imagined as a familiar New Zealand city, London came to be used that way. Visitors toured Londons iconic geography, finding their heritage in its monumental architecture. New Zealand writers haunted Fleet Street, arriving broke but expecting to use London as a natural extension of their working world. Soldiers on leave during two world wars went broke there, spending their pay in a city that was their home away from home. Histories have missed it, but for the best part of a century, New Zealands most important city was 12,000 miles away. It was New Zealands London, and it shaped our culture. This book is about that relationship. Londons role was much more significant than our histories have allowed. By overlooking it, we have misunderstood a key part of our past.

LOCATING LONDON

London may have been a constant presence in New Zealands cultural life, but it has had only a marginal presence in our histories. Like other white settler societies, New Zealand has a strong vein of nationalist historiography. The formative era of New Zealand history writing, ushered in by Keith Sinclair and W. H. Oliver, inaugurated a continuing interest in examining and identifying New Zealands distinctive nationalism. These histories emphasised the steady, if gradual, emergence of an independent New Zealand identity even if they did not agree on when exactly it emerged rather than the continuing effect of Englands metropolis on New Zealands culture. Indeed, those effects were considered obstacles to the development of an authentic, local identity, and lingering ties with Home were treated as vaguely embarrassing examples of cultural immaturity. Sinclair described colonial New Zealand as having grown up in an English dream, one that had profound and pathetic consequences.

Recently, though, historians in New Zealand, Canada and Australia have begun to reassess the nature and extent of their imperial relationship. New studies have described more complex and subtle processes of disengagement.

Despite growing interest in the roles of Britain and its former colonies in the construction of British identities, New Zealand historians have only slowly begun to revisit this aspect of our past. In a postcolonial version of that older, nationalist reluctance, the re-examination of Britishness in the New Zealand context is considered awkward, uncomfortable and even irrelevant on the basis that reveal[ing] a British past is assumed to reassert it in the present. for settlers. But, as this book argues, the construction of New Zealand as British, in different form, continued well into the twentieth century, with London at the heart of that process. In New Zealand, Britishness was not simply a natural consequence of settler demography, Home was not just a nostalgic habit and London as cultural capital was more than a symbol of colonial immaturity. They were instead elements of a complex cultural relationship that played a crucial role in recreating old colonial New Zealand as a modern, first-world member of empire.

If Londons cultural role has been neglected in New Zealands histories, then new histories of empire have returned the favour. Increasingly, if not unanimously, British historians have come to see the imperial experience as an integral part of domestic life. As historians such as John MacKenzie have argued, empire is intricately woven into metropolitan culture both high and low, found in cups of tea and in popular fiction, in music halls as well as in museums, in the definition of masculinity and in the development of womens suffrage. laying claim to Britishness upset this imperial order. But when visitors from white settler colonies such as New Zealand followed the same tourist trails, they were not merely returning Home, but helping reinforce Londons identity as that home. As appropriate inheritors of the civilised centre, their enthusiastic acquisition of the metropolis helped strengthen rather than destabilise the hierarchy of empire.