The I Ching: The Interaction of Yin and Yang

The I Ching (The Book of Changes) is one of the most ancient writings in world literature. Although the nucleus was probably written down around the eleventh century BC , according to tradition the origin of this Chinese book of wisdom lies even further back in time.

The I Ching is based on the idea that all phenomena in the universe are founded on two opposing forces. Initially these forces were referred to simply as dark and light. Later, the terms were changed to Yin and Yang. Yin is the female, passive, flexible and gentle force at work in the universe, and Yang, the male principle, is characterised by decisiveness, activity, hardness and a certain rigidity. In the I Ching, all forms of life and therefore also the functions of the human spirit are associated with Yin and Yang. The Yin and Yang forces are at work in all processes of growth and decay, in the cycle of the seasons, in everything we think, do, experience and undertake. In fact, without the interaction of Yin and Yang, there would be no life.

As early as the fifth century BC , the famous Chinese philosopher, Tswang Tse, told us that Yin and Yang create and destroy each other in an eternal roundelay:

Hence the physical world with its cycle of seasons, hence human nature with its likes and dislikes, its love and hate, hence the difference between the sexes, their unification and procreation, hence the varying states, such as prosperity and adversity, safety and peace, hence the abstract concepts such as cause and effect and the cyclical processes in which end and beginning follow each other.

From Yin and Yang to trigrams and hexagrams

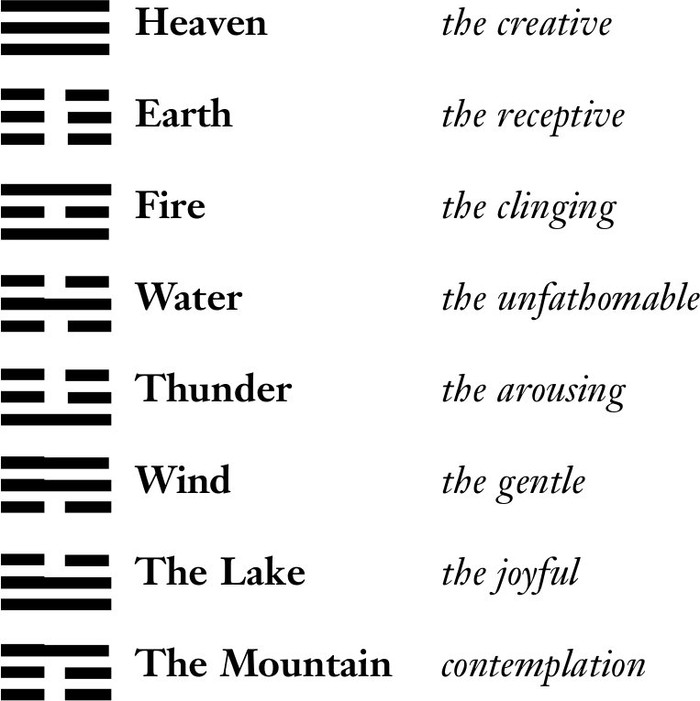

The I Ching clarifies the interaction of Yin and Yang of which Tswang Tse spoke, based on a pattern of six lines, consisting of broken  Yin lines and solid

Yin lines and solid  Yang lines. The book contains sixty-four of these patterns, which, as they consist of six lines, are called hexagrams. The basis of these hexagrams are two patterns consisting of three lines, trigrams, which look like this and are associated with

Yang lines. The book contains sixty-four of these patterns, which, as they consist of six lines, are called hexagrams. The basis of these hexagrams are two patterns consisting of three lines, trigrams, which look like this and are associated with

These eight archetypes, or trigrams, can together form sixty-four combinations, resulting in the aforementioned sixty-four hexagrams.

The I Ching opens with hexagram 1, the creative, a purely Yang hexagram, comprising two sets of three solid lines. This first hexagram is followed by hexagram 2, the receptive, a 100 per cent Yin hexagram, comprising six Yin lines. These two hexagrams represent the Yin and Yang principle in its purest form. In the following hexagrams, the Yin and Yang lines form combinations, providing an image of the various states of existence.

According to the I Ching, everything is in constant motion

The sixty-four hexagrams illustrate all the combinations in which Yin and Yang can occur in life. They give not only an image of our physical and spiritual state, but also show what opportunities or dangers are entailed in the Yin-Yang relations expressed in a particular hexagram, both psychologically and socially. An excess of Yang, for example, can quickly lead to carelessness, arrogance, insensitivity, fanaticism, aggression and a rigid, intolerant attitude to life. If the balance in life leans too far towards the Yin side, we run the risk of falling prey to passivity, exaggerated obedience, exploitation, petty-mindedness or fear of failure.

The I Ching as not only a guide, but also a counsellor

If we consult the I Ching, seeking one of these sixty-four hexagrams, what we end up with is not only a Yin-Yang pattern consisting of six lines, but also practical advice based on this pattern, which spurs us on, in one instance, to strengthen something or to continue upon the course we have already chosen and, in other instances, to weaken something, to bide our time or even to undertake nothing. The essence is always the search for the right balance: how we can make the best of a situation. The book therefore aids those consulting the oracle with positive advice at times, or a negative judgement at others. If there is any disharmony, the I Ching not only pinpoints the problem; it also devotes extensive attention to the remedies. Change, harmony and the search for balance constitute the key words here. Naturally, we are free to choose whether to follow this advice and these suggestions and tailor their interpretation to fit our personal situation.

The eternal roundelay of life, encompassed in the I Ching in sixty-four stages, illustrates the old adage that you should never say die, that nothing in life is doomed for ever to remain as it is. It shows that the opportunities for changing, learning and experiencing in life are virtually inexhaustible. In the I Chings notes on life, there is no approval or disapproval in any absolute sense. An attitude that is praised one moment is disapproved of in another. That everything we experience or are offered in life is nothing more than a lesson is the philosophy of the I Ching. It always happens at the right time and always occurs in the right place. The only absolute wrong is inflexibility, stagnation or rigidity. Every situation, no matter how unpleasant or undesired, opens the door to insight and self-knowledge through change; every time we miss that chance, we sin against ourselves and against life.

The quality of the question determines the quality of the answer

The actions you need to perform to consult the I Ching are as simple as using the telephone. Nevertheless, it would be extremely irreverent and a sign of great superficiality to put consulting the I Ching on a par with something like using the phone. A telephone can be used to dispel boredom and you can use it for any unimportant question or announcement, just as often as you wish. You need not know anything about electronics to be able to communicate optimally via the telephone.

When consulting the I Ching, precisely the opposite applies in every aspect. There is no point in questioning this ancient book of wisdom unless you have serious cause. It goes without saying that superficial questions such as What shall I do this evening? or Shall I buy a new bicycle? dont fall into this category. A question can only be considered serious when the way you conduct your life and how you behave in society with regard to others play a role. The better and more broadly the question is formulated, the more significant the answer will be. The guideline is not to pose such questions as Will I get my stolen bicycle back? or to enquire after matters of fact, such as Will I get the job or not? It is better and more useful to investigate the issue of why you are always losing things, how you should tackle theft in general, or what you should or should not do to get a job.

This may make it clear why there is no point in consulting the I Ching every day or even several times a day. Even if you dont like the answer or it seems more of a riddle, only consult the book again when a change in circumstances surrounding the question gives cause to do so. Even if you are initially unsure of what to do with the answer you receive to your question, it is advisable to wait a few days before making another attempt. The significance of an answer often only becomes clear with time.

Yin lines and solid

Yin lines and solid  Yang lines. The book contains sixty-four of these patterns, which, as they consist of six lines, are called hexagrams. The basis of these hexagrams are two patterns consisting of three lines, trigrams, which look like this and are associated with

Yang lines. The book contains sixty-four of these patterns, which, as they consist of six lines, are called hexagrams. The basis of these hexagrams are two patterns consisting of three lines, trigrams, which look like this and are associated with