My thanks are due to Doctor Fritz Kaufmann of the University of Buffalo for his kindness in reading the manuscript. Chapter 26 of this book was first published in the Review of Religion, 1942 ; parts of chapters 17 and 22 in the Journal of Religion , 1943; and in the Reconstructionist, 1944. I am grateful to the editors for permission to reproduce the material.

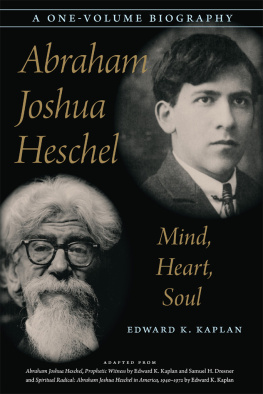

Books by Abraham Joshua Heschel

MORAL GRANDEUR AND SPIRITUAL AUDACITY

THE WISDOM OF HESCHEL

A PASSION FOR TRUTH

ISRAEL: AN ECHO OF ETERNITY

THE INSECURITY OF FREEDOM

WHO IS MAN?

THEOLOGY OF ANCIENT JUDAISM (two volumes)

THE SABBATH

THE EARTH IS THE LORDS

MANS QUEST FOR GOD

GOD IN SEARCH OF MAN

MAN IS NOT ALONE

MAIMONIDES

ABRAVANEL

THE QUEST FOR CERTAINTY IN SAADIAS PHILOSOPHY

THE PROPHETS

There are three aspects of nature which command mans attention: power, loveliness, grandeur. Power he exploits, loveliness he enjoys, grandeur fills him with awe. We take it for granted that mans mind should be sensitive to natures loveliness. We take it equally for granted that a person who is not affected by the vision of earth and sky, who has no eyes to see the grandeur of nature and to sense the sublime, however vaguely, is not human.

But why? What does it do for us? The awareness of grandeur does not serve any social or biological purpose; man is very rarely able to portray his appreciation of the sublime to others or to add it to his scientific knowledge. Nor is its perception pleasing to the senses or gratifying to our vanity. Why, then, expose ourselves to the disquieting provocation of something that defies our drive to know, to something which may even fill us with fright, melancholy or resignation? Still we insist that it is unworthy of man not to take notice of the sublime.

Perhaps more significant than the fact of our awareness ofthe cosmic is our consciousness of having to be aware of it, as if there were an imperative, a compulsion to pay attention to that which lies beyond our grasp.

The power of expression is not the monopoly of man. Expression and communication are, to some degree, something of which animals are capable. What characterizes man is not only his ability to develop words and symbols, but also his being compelled to draw a distinction between the utterable and the unutterable, to be stunned by that which is but cannot be put into words.

It is the sense of the sublime that we have to regard as the root of mans creative activities in art, thought and noble living. Just as no flora has ever fully displayed the hidden vitality of the earth, so has no work of art ever brought to expression the depth of the unutterable, in the sight of which the souls of saints, poets and philosophers live. The attempt to convey what we see and cannot say is the everlasting theme of mankinds unfinished symphony, a venture in which adequacy is never achieved. Only those who live on borrowed words believe in their gift of expression. A sensitive person knows that the intrinsic, the most essential, is never expressed. Mostand often the bestof what goes on in us is our own secret; we have to wrestle with it ourselves. The stirring in our hearts when watching the star-studded sky is something no language can declare. What smites us with unquenchable amazement is not that which we grasp and are able to convey but that which lieswithin our reach but beyond our grasp; not the quantitative aspect of nature but something qualitative; not what is beyond our range in time and space but the true meaning, source and end of being, in other words, the ineffable.

The ineffable inhabits the magnificent and the common, the grandiose and the tiny facts of reality alike. Some people sense this quality at distant intervals in extraordinary events; others sense it in the ordinary events, in every fold, in every nook; day after day, hour after hour. To them things are bereft of triteness; to them being does not mate with non-sense. They hear the stillness that crowds the world in spite of our noise, in spite of our greed. Slight and simple as things may bea piece of paper, a morsel of bread, a word, a sighthey hide and guard a never-ending secret: A glimpse of God? Kinship with the spirit of being? An eternal flash of a will?

Part company with preconceived notions, suppress your leaning to reiterate and to know in advance of your seeing, try to see the world for the first time with eyes not dimmed by memory or volition, and you will detect that you and the things that surround youtrees, birds, chairsare like parallel lines that run close and never meet. Your pretense of being acquainted with the world is quickly abandoned.

How do we seek to apprehend the world? Intelligence inquires into the nature of reality, and, since it cannot work without its tools, takes those phenomena that appear to fit its categories as answers to its inquiry. Yet, when trying to holdan interview with reality face to face, without the aid of either words or concepts, we realize that what is intelligible to our mind is but a thin surface of the profoundly undisclosed, a ripple of inveterate silence that remains immune to curiosity and inquisitiveness like distant foliage in the dusk.

Analyze, weigh and measure a tree as you please, observe and describe its form and functions, its genesis and the laws to which it is subject; still an acquaintance with its essence never comes about. Looking at things through the medium of our thoughts remains an act of crystal-gazing; the pictures we induce happen to be part of the truth, nevertheless, what we see is a mental image, not the things themselves. Hastily running down the narrow path of time, man and world have no station, no present, where they can get acquainted. Thinking is never co-temporal with its object, for it follows the process of perception that took place previously. We always deal in our thoughts with posthumous objects. Acting always behind perception, thinking has only memories at its disposal. Its object is a matter of the past, like a moment before the last: so close and so far away. Knowledge, therefore, is a set of reminiscences, and, our perception being always incomplete and full of omissions, a subsequent combination of random memories. We rarely discover, we remember before we think; we see the present in the light of what we already know. We constantly compare instead of penetrate, and are never entirely unprejudiced. Memory is often a hindrance to creative experience.

Thinking is fettered in words, in names, and names describe that which things have in common. The individual and unique in reality is not captured by names. Yet our mind necessarily compromises with words; with names. This is an additional reason why we rarely find the entrance to the essence. We cannot even adequately say what it is that we miss.

Is it necessary to ascend the pile of ideas in order to learn that our solutions are enigmas, that our words are indiscretions? A world of things is open to our minds, but often it appears as if the mind were a sieve in which we try to hold the flux of reality, and there are moments in which the mind is swept away by the tide of the unexplorable, a tide usually stemmed but never receding.