Impro

Impro is the most dynamic, funny, wise, practical and provocative book on theatre craft that I have ever read (James Roose-Evans).

Keith Johnstones involvement with the theatre began when George Devine and Tony Richardson, artistic directors of the Royal Court Theatre, commissioned a play from him. This was in 1956. A few years later he was himself Associate Artistic Director, working as a play-reader and director, in particular helping to run the Writers Group. The improvisatory techniques and exercises evolved there to foster spontaneity and narrative skills were developed further in the actors studio, then in demonstrations to schools and colleges and ultimately in the founding of a company of performers, called The Theatre Machine.

Divided into four sections, Status, Spontaneity, Narrative Skillsand Masks and Trance, arranged more or less in the order a group might approach them, the book sets out the specific techniques and exercises which Johnstone has himself found most useful and most stimulating. The result is both an ideas book and a fascinating exploration of the nature of spontaneous creativity.

The books incredible achievement is its success in making improvisation re-live on the page Get Mr Johnstones fascinating manual and I promise you that if you open at the first page and begin to read you will not put it down until the final page. (Yorkshire Post)

He suggests a hundred practical techniques for encouraging spontaneity and originality by catching the subconscious unawares. But what makes the book such fun is the teachers wit. Here is an inexhaustible supply of zany suggestions for unfreezing the petrified imagination. (Daily Telegraph)

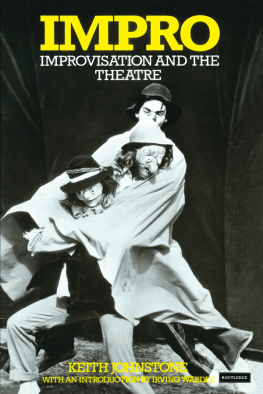

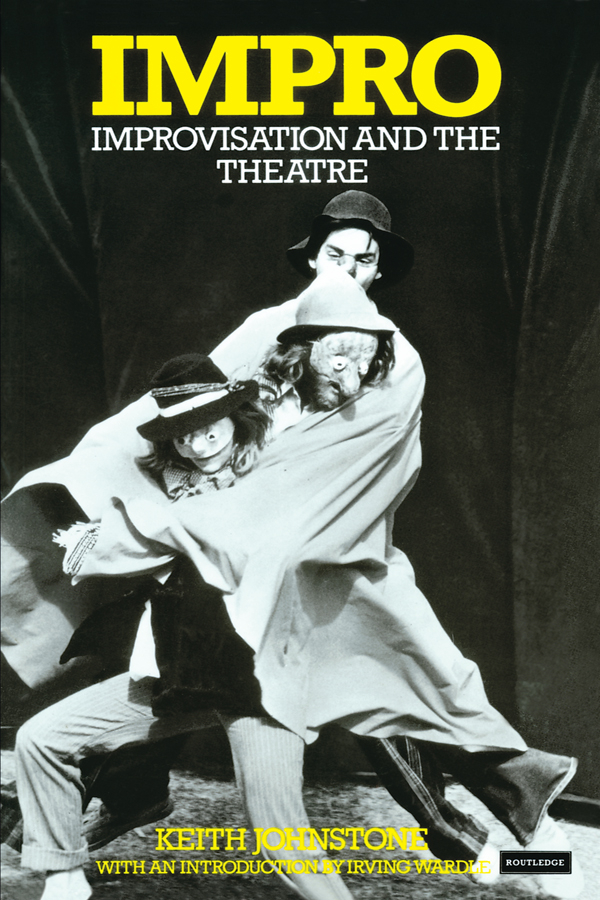

The front cover shows a moment from The Defeat of Giant Big Nose, an improvised childrens play presented by Keith Johnstones Loose Moose Theatre Company in Calgary, Alberta. Photo by Deborah A. lozzi.

Also Available

Eugenio Barba

DICTIONARY OF THEATRE ANTHROPOLOGY:

The Secret Art of the Performer

Jean Benedetti

STANISLAVSKI: AN INTRODUCTION

Augusto Boal

GAMES FOR ACTORS AND NON-ACTORS

Richard Boleslavsky

ACTING: THE FIRST SIX LESSONS

Jean Newlove

LABAN FOR ACTORS AND DANCERS

Constantin Stanislavski

AN ACTOR PREPARES

BUILDING A CHARACTER

CREATING A ROLE

MY LIFE IN ART

STANISLAVSKIS LEGACY

IMPRO

Improvisation and the Theatre

KEITH JOHNSTONE

With an Introduction by

IRVING WARDLE

First published in paberback in 1981 by Eyre Methuen Ltd

Published 2015 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Published by Routledge / Theatre Arts Books

711 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Reprinted 1982, 1983, 1985, 1987

Reprinted in 1989 by Methuen Drama,

Reprinted 1990, 1991, 1992

Originally published in hardback

by Faber and Faber Ltd in 1979.

Corrected for this edition by the author

Copyright 1979, 1981 by Keith Johnstone

Introduction copyright 1979 by Irving Wardle

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available on request

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

ISBN 13: 978-0-87830-117-1

ISBN 13: 978-0-20344-629-4 (eISBN)

Contents

Introduction

If teachers were honoured in the British theatre alongside directors, designers, and playwrights, Keith Johnstone would be as familiar a name as are those of John Dexter, Jocelyn Herbert, Edward Bond and the other young talents who were drawn to the great lodestone of the Royal Court Theatre in the late 1950s. As head of the Courts script department, Johnstone played a crucial part in the development of the writers theatre, but to the general public he was known only as the author of occasional and less than triumphant Court plays like Brixham Regatta and Performing Giant. As he recounts in this book, he started as a writer who lost the ability to write, and then ran into the same melancholy impasse again when he turned to directing.

What follows is the story of his escape.

I first met Johnstone shortly after he had joined the Court as a los-a-script play-reader, and he struck me then as a revolutionary idealist looking around for a guillotine. He saw corruption everywhere. John Arden, a fellow play-reader at that time, recalls him as George Devines subsidised extremist, or Keeper of the Kings Conscience. The Court then set up its Writers Group and Actors Studio, run by Johnstone and William Gaskill, and attended by Arden, Ann Jellicoe and other writers of the Courts first wave. This was the turning point. Keith, Gaskill says, started to teach his own particular style of improvisation, much of it based on fairy stories, word associations, free associations, intuitive responses, and later he taught mask work as well. All his work has been to encourage the rediscovery of the imaginative response in the adult; the refinding of the power of the childs creativity. Blake is his prophet and Edward Bond his pupil.

Johnstones all-important first move was to banish aimless discussion and transform the meetings to enactment sessions; it was what happened that mattered, not what anybody said about it. It is hard now to remember how fresh this idea was in 1958, Ann Jellicoe says, but it chimed in with my own way of thinking. Other members were Arnold Wesker, Wole Soyinka, and David Cregan as well as Bond who now acknowledges Johnstone as a catalyst who made our experience malleable by ourselves. As an example, he cites an exercise in blindness which he later incorporated in his play Lear; and one can pile up examples from Arden, Jellicoe, and Wesker of episodes or whole plays deriving from the groups work. For Cregan, Johnstone knew how to unlock Dionysus : which came to the same thing as learning how to unlock himself.

From such examples one can form some idea of the special place that teaching occupied in Devines Royal Court; and how, in Johnstones case, it was the means by which he liberated himself in the act of liberating others. He now hands over his hard-won bunch of keys to the general reader. This book is the fruit of twenty years patient and original work; a wise, practical, and hilariously funny guide to imaginative survival. For anyone of the artist type who has shared the authors experience of seeing his gift apparently curl up and die, it is essential reading.

One of Johnstones plays is about an impotent old recluse, the master of a desolate castle, who has had the foresight to stock his deep-freeze with sperm. There is a power-cut and one of the sperm escapes into a goldfish bowl and then into the moat where it grows to giant size and proceeds to a whale of a life on the high seas.

That, in a nut-shell, is the Johnstone doctrine. You are not imaginatively impotent until you are dead; you are only frozen up. Switch off the no-saying intellect and welcome the unconscious as a friend: it will lead you to places you never dreamed of, and produce results more original than anything you could achieve by aiming at originality.

Next page