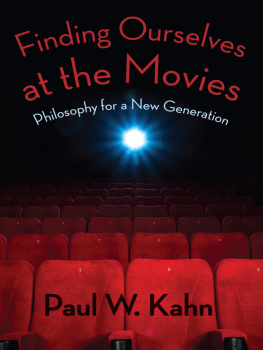

FINDING OURSELVES AT THE MOVIES

Finding Ourselves at the Movies

PHILOSOPHY FOR A NEW GENERATION

Paul W. Kahn

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53602-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kahn, Paul W., 1952

Finding ourselves at the movies : philosophy for a new generation / Paul W. Kahn.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16438-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53602-8 (ebook)

1. Motion picturesPhilosophy. I. Title.

PN1995.K255 2013

791.43684dc23 2013016275

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Jacket design: Catherine Casalino

Jacket photograph: Nejron Photo-Fotolia.com

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

Two men encounter each other near the law courts. one is there to defend against a charge of impiety; the other is there to accuse his own father of manslaughter. The former asks the latter to help him to understand the nature of piety. A conversation on family, justice, and law begins. The conversation does not resolve any of this, but it moves through a variety of possibilities, creating a kind of space, or pause, in the daily routine. In that space the speakers examine what they believe and how they should act. on another occasion the same questioner has gone to the suburbs to watch a festival. The son of an old acquaintance invites him home to see his father. After greeting the father, the younger guest asks his host to tell him what it is like to be old. The conversation quickly leads to questions of justice, which involve both young and old. Again, there is a pause in the daily routine, while the participants take a hard look at their own beliefs and practices. They exercise their imaginations, as well as their critical faculties, for they try to imagine an ideal political arrangementa project in which they are only partially successful. At the end of the conversation they return to the business of their daily lives.

These are the framing scenes of two of Platos dialogues, as familiar to many as the scene of Abraham taking Isaac up the mountain. Philosophys origins are no more esoteric than the biblical stories. Just as religion begins with narrative, not theology, so philosophy begins with narrative, not abstraction. Plato may have done philosophy, but he wrote dramas. In his dialogues we are offered an imaginative construction that has a narrative line, as well as philosophical arguments. The narrative is not just something that gets in the way of the arguments. Because narrative and argument are always intertwined, these texts require interpretation, not reduction to abstract propositions. We are asked, just like the characters in the dramas are asked, to pause, to try to answer questions, to reflect on what is said, and to respond.

One of the messages of these dramas is that philosophy is a conversation that can happen anywhere. It is an engagement that can take place on the street or over dinner. Philosophy is not extraordinary, but a continuation of reflective practices that are, or can be, a part of our lives. I want to recover something of this tradition for philosophy. Today, we no longer have the time or the knowledge of each other that would make possible a pause for argument on our way to court or anywhere else. We live in different communities spread out across the nation and, increasingly, across the globe. The people we deal with are more than likely strangers. We husband our time and cannot simply take a break for reflective inquiry in our busy work schedules. Yet we are not so far from the world of Plato that we no longer recognize the point of the dialogues. We still have an interest in serious reflection and self-examination. We do want to examine our beliefs; we do want to understand ourselves better. We want to ask each other why we think and act as we do. our curiosity about ourselves remains as strong as ever.

To engage in this conversation today, we need common objects to talk about. We are not all going to read Platos dialogues. Nor do we have the easy familiarity with each other that comes from living in a relatively small city with little contact with the larger world. Increasingly, what we have in common is the movies. here we can find a point from which to begin a conversation about our shared beliefs and practices. Philosophy can begin as we leave the theater and talk to each other about what we just experienced. Today, we often do not even share the space of the theater, yet still we have the movies as common texts. The movies connect us across generationshere I find a common ground with my students, as well as with my parents. Movies give us a ground on which to strike up a conversation with a stranger. We ask each other, have you seen any good movies lately? and find we have something in common to talk about.

A philosophical work that discusses popular culture is not itself a work of popular culture. I am not taking up the role of movie critic. I have little to say on whether any of the movies I discuss are worth seeing. Neither is this a work in film theory, although I hope that those interested in that discipline will find something of value here. I spend no time on the history of film or even with the recognized film classics. I emphasize narrative over the other aspects of creativity and production that go into a film. This is not because narrative is more important but because my questions go to what a film means and what that meaning tells us about ourselves. The film theorists rightly point out that narrative does not stand alone, that a films meaning relies on its many other elements: for example, music, lighting, cinematography, editing, composition. I dont disagree. My ambition, however, is not to study film or the experience of film but to explore the accounts we give of ourselves and our communities.

This book will strike some readers as fitting neither the genre of philosophy nor that of film studies. I avoid the scholarly apparatus of both disciplines because my intended audience is not the professionals. It is my hope to do serious philosophy while speaking of one of the most ordinary elements of our common lifewhat is playing at the local cinema. For that reason I avoid the form and style of conventional scholarly texts. I keep notes to a minimum, crediting sources of specific ideas and providing basic information on the films I discuss. For those readers interested in the broader literature on which I draw, I provide some orientation in the bibliographic essays that follow the notes.

Socrates reminds us that the stakes are always high when we try to understand even our daily routines. I dont expect anyone to suggest that I drink hemlock, but I do expect a lot of professionals to tell me that this is just not the way it is done. That, however, is just the point: we need a new beginning to get back to what has been most important in the Western practice of philosophy. one place to begin is at the movies.