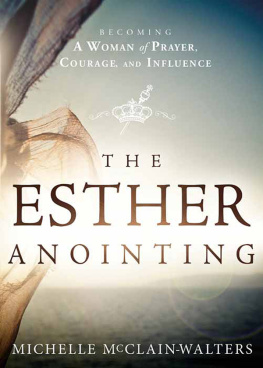

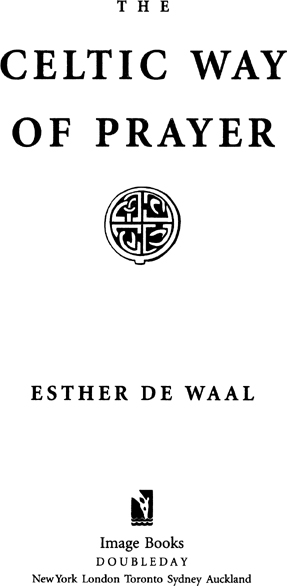

Esther de Waal - The Celtic Way of Prayer

Here you can read online Esther de Waal - The Celtic Way of Prayer full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: The Crown Publishing Group, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Celtic Way of Prayer

- Author:

- Publisher:The Crown Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Celtic Way of Prayer: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Celtic Way of Prayer" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Celtic Way of Prayer — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Celtic Way of Prayer" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I should like to acknowledge with great gratitude permissions from the following:

Trustees of the Scottish Academic Press for permission to quote so widely from the Carmina Gadelica Vol. I & II.

Fr. Noel Dermott O'Donoghue and T & T Clark Publishers for the new rendering of St. Patrick's Breastplate.

Dr. Oliver Davies and Dr. Fiona Bowie and SPCK, for the recent translations of early Welsh material taken from their anthology Celtic Christian Spirituality.

Thomas Owen Clancy & Gilbert Markus and The Edinburgh University Press for the lines from the Altus Prosator and verses from Cantemus in Mon Dei from Iona, the Earliest Poetry of a Celtic Monastery.

Cynthia and Saunders Davies and The Church of Wales Publications for Euros Bowen's poem Gloria.

Gillian Clarke and Carcanet for a few lines from her poem Fires on Llyn.

THE REDISCOVERY OF the Celtic world has been an extraordinary revelation for many Christians in recent years, an opening up of the depths and riches within our own tradition that many of us had not before suspected. As I reflect on what it has meant to me, I think that above all it has enriched my understanding of prayer. It has taught me, and encouraged me into, a deeper, fuller way of prayer. I have come to see that the Celtic way of prayer is prayer with the whole of myself, a totality of praying that embraces the fullness of my own personhood, and allows me not only to pray with words but also, more important, with the heart, the feelings, using image and symbol, touching the springs of my imagination.

I like to think of it as a journey into prayer. The Celtic understanding of journeying is in itself so rich and so significant. It is peregrinano, seeking, quest, adventure, wandering, exileit is ultimately a journey, as I try to show in the first chapter, to find the place of my resurrection, the resurrected self, the self that I might hope to be, to become, the true self in Christ. This journey is possible only because I am finding my rootsthat familiar paradox known in all monastic life and a reflection of basic human experience, that only if one is rooted at home in one's own self, in the place in which one finds oneself, is one able to move forward, to open up new boundaries, both exterior and interior, in other words, to embark on a life of continual and never-ending conversion, transformation. To find my roots takes me back to the part of my self that is more ancient than I am, and this is, of course, the power of the Celtic heritage. In my own case there are both my family roots, which are Scottish, and the place where I was born, and where I now once again live, which is the Border country of Wales. But for any of us the Celtic tradition is the ancient or elementala return to the elements, the earth, stone, fire, water, the ebb and flow of tides and seasons, the pattern of the year as it swings on its axis from Samhaine, November 1, when all grows dark, to Beltaine, May 1, the coming of light and spring. To pray the Celtic way means above all to be aware of this rhythm of dark and light. The dark and the light are themselves symbols of the Celtic refusal to deny darkness, pain, suffering and yet to exult in rejoicing, celebration in the fullness and goodness of life. This is in itself a recognition of the fullness of my own humanity.

Coming from the farthest fringes of the Western world, Celtic Christianity (an expression I prefer to use rather than speaking of the Celtic Church) keeps alive what is ancient Christian usage, usage which like that of the East comes from a deep central point before the Papacy began to tidy up and to rationalize. This was more difficult in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, the Isle of Man, Cornwall and Brittany, the main Celtic areas, simply because of geographical distance and the lack of towns. This point is of more than antiquarian interest: It also speaks to me symbolically, taking me back to the ancient, the early, both in my own self, and in the experience of Christendom, where I encounter something basic, primal, fundamental, universal. I am taken back beyond the party labels and the denominational divisions of the Church today, beyond the divides of the Reformation or the schism of East and West. I am also taken beyond the split of intellect and feeling, of mind and heart, that came with the growth of the rational and analytical approach that the development of the universities brought to the European mind in the twelfth century. Here is something very profound. This deep point within the Christian tradition touches also some deep point in my own consciousness, my own deepest inner self.

This tapestry of the riches of the Celtic way of prayer has about it something of the variety of shapes and colors that I find in a page of the Book of Kelts, and so I find myself asking where and how we can begin to unravel one of these extraordinary spirals or threads so that it leads us on into our exploration. I think that the essential starting point is the fact that Celtic Christianity was essentially monastic, as indeed the origins of Christianity in the whole of Britain were strictly monastic.

Those earliest years in Ireland and Wales forged a powerful mix between monastic Christianity and what existed already in the people to whom this Christian message was now brought. It was the way in which Christianity responded to what it found in these lands that gives it its unique character and emphasis. The Celtic countries lay on the edge of the known Western world, largely outside the Roman Empire, a people lacking the social molds and mental framework and cultural infrastructure the Roman Empire brought elsewhere. These were a rural people, living close to the earth, close to stone and water, and their religious worship was shaped by their awareness of these elemental forces. They were a rural people for whom the clan, the tribe, and kinship were important, a close-knit people who thought of themselves in a corporate way as belonging to one another. They were a warrior people, a people whose myths and legends told them of heroes and heroic exploits. Above all, they were a people of the imagination, whose amazing artistic achievements in geometric design, filigree work, and enameling can be seen in La Tene art, and whose skill with words (spoken not written) flowered in poetry and storytelling. This was a society in which the poet held a highly respected place, played a professional role, and where storytelling was taken seriously and demanded many years of study and learning. All this was taken up by a Christianity that was not afraid of what it found but felt that it was natural to appropriate it into the fullness of Christian living and praying. So the Celtic way of prayer is a reflection of this: It is elemental, corporate, heroic, imaginative. This is its gift to us.

As I have gone deeper in my exploration of the Celtic heritage, I have found that it has touched me profoundly at many levels that had not hitherto been a familiar part of my twentieth-century upbringing and education. I discovered that if I wanted to encounter Celtic Christianity, I had to look at poetry, and so I found myself being taken into the world of poetry and song. My own religious upbringing had been so intellectual and cerebral, a matter of going to church, of reciting the Creed, of saying prayers. And instead here was a world that told me books were not enough, that books could not express the wonder of the world that God had made:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Celtic Way of Prayer»

Look at similar books to The Celtic Way of Prayer. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Celtic Way of Prayer and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.