Contents

Page List

Guide

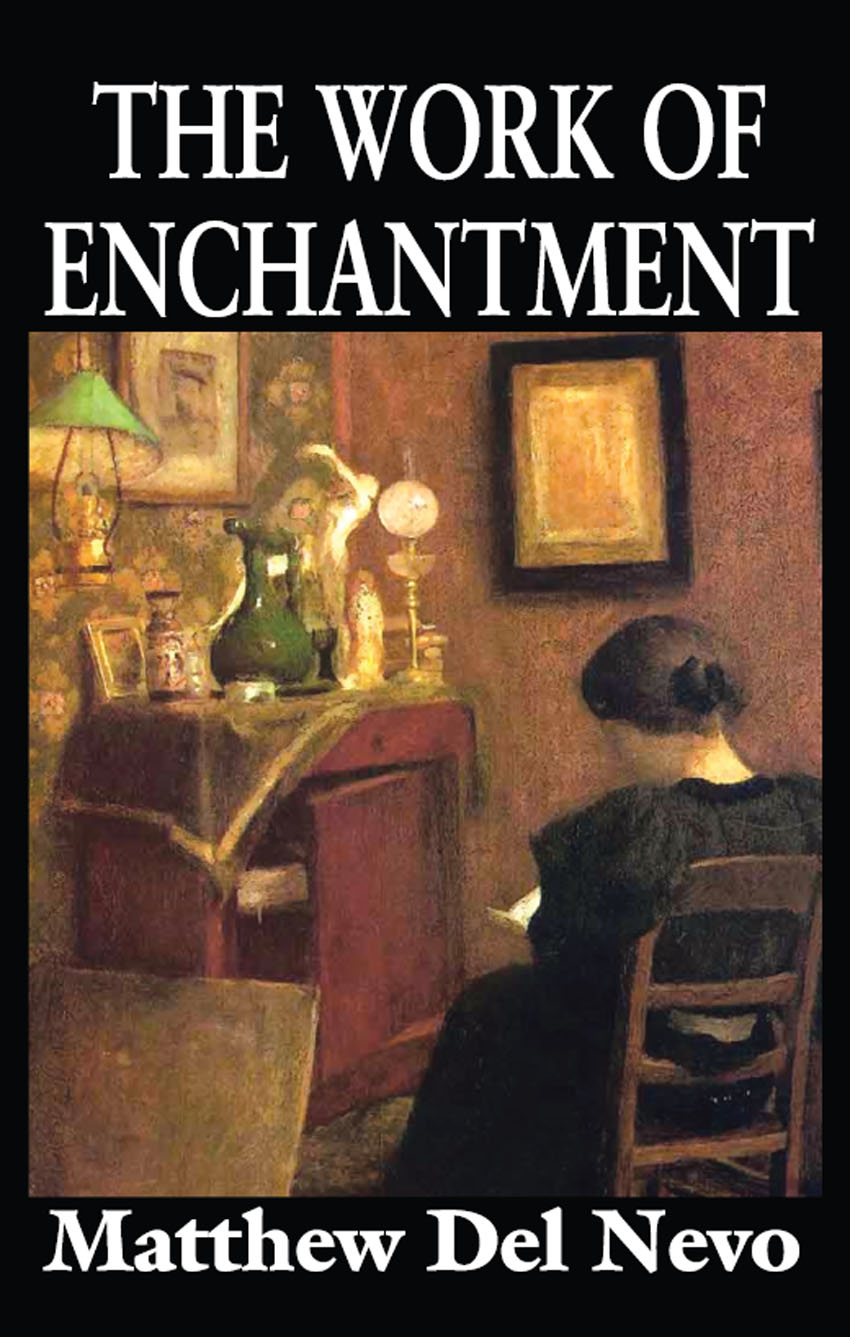

THE WORK OF ENCHANTMENT

THE WORK OF ENCHANTMENT

Matthew Del Nevo

First published 2011 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2011 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2010045561

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Del Nevo, Matthew.

The work of enchantment / Matthew Del Nevo.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-1860-5 (acid-free paper)

1. Aesthetics. 2. Charm. I. Title.

BH301.C4D45 2011

111.85dc22

2010045561

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-1860-5 (hbk)

There is probably no specialist knowledge in this area.

Sigmund Freud

Contents

I wrote this book on freezing winter days and nights in Shanghai. I think its pages carry some of the urgency of that time and place, which is undergoing so much change and uncertaintyas we all are, whether city-bound or not.

In those chapters of this book where I discuss the writing of Marcel Proust, I have used some long quotations interwoven with my own writing. This is a stylistic device I found and liked in the work of the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel in his lectures on the German poet Rilke. The stylistic device served there to introduce the readers (or listeners, as they would have been originally) to Rilke in a substantial, first-hand way, and at the same time to provide some insight into a text which may otherwise have seemed rather arcane or difficult: Rilke is not an easy poet who you can just pick up and read and understand, without first sharing something of his sensibility. The stylistic device allows for both the reading of the poet (or Proust, in my case) and some orientation as to the sensibility required for admiration and understanding.

This is a work about enchantment. Enchantment, today, is something we lack, something which even children miss out on, and it is in fact being extirpated from childhood by the aggressive and domineering mass-culture industries. Not just children and young people lack enchantment: so do adults. Enchantment, however, is something that the soul cannot do without, unless it is to starve. In first-world countries we are rich in every conceivable way, except the way of the soul, which is what this book is about. One in five people suffers mental illness in the land of plenty; but, in places where one might expect people to snap under real hardship and hopelessness, we find mental illness scarce, mental and physical obesity non-existent, and that, incredible to us, people are relatively cheerful. To the soul-starved westerner, this seems the wrong way round. A book cannot even hope to redress a cultural situation so far gone, and, anyhow, the situation is so complex that it is all but impossible to diagnose in any authoritative way. However, I am impelled to talk about enchantment.

This book is particularly about the experience of enchantment. Enchantment is something most of us can remember from childhood and indeed associate with that period of our lives. We find our own children enchanting, at a later stage, and then our grandchildren. However, enchantment, although perhaps the prerogative of the child, is nothing childish. Our artistic heritages are rich in enchantment and they try to teach it to us. They try to do this not by didactic methodsdidactic art is bad artbut by initiating us. Art is an initiatory experienceat least, we may say this of good art, which is art that stands the test of time. Through art, as adults, we can experience enchantment in a new way that is richer than that experienced in childhood because, as adults, we are more conscious and appreciative. Art therefore gives us something, and one of the gifts it can bringthat of enchantmentis a gift of great importance. It is life enriching. Yet, we cannot experience enchantment unless we have receptive ability, and this is where culture and education come in. We stand bored and uninterested like children before artworks if we have not cultivated within ourselves the power to appreciate, to receive what great art has to give. Our approach in this book will be to cultivate and mediate the possibility of initiation present in great works of literature, picking on a very limited range. These are great because of their uncontested power of initiation, and they are of special worth when it comes to enchantment. These are works associated with the following names: Adorno, Proust, Rilke, and Goethe.

Enchantment is not a trivial subject by any stretch of the imagination. Enchantment is bound up with literature, art, philosophy, and religionand subsidiary studies in psychology, sociology, and culture as well. I could go on. Enchantment is not for the specialist in any of these studies, but for everyone. The whole point of it is that it is quintessentially human. The trouble is that most of us lose touch with it after a certain age, so it is consigned to childrens books; and we imagine art has to do with something else. But of course when we look at a lot of contemporary art, it often does have to do with something else. Art is sick. Culture is sick too. When art has lost its charm, even a perverse charm but a charm nonetheless, it is sick. In a culture where charm is an archaic word which no one usesand other more commercially viable values take its placeand where codes of practice replace manners, culture is not well either. But of course art and culture interplay and feed off each other. This is where critical theory comes in: it critiques this situation, unmasking it, trying to revolutionize it, ultimately for the good, if that is possible. At the center of this critique (if we may call it that), is not a new theory, but a defense of the humanities, of philosophy, religion, art and, in this book, of beauty, as the major criterion of the true and the good.

Enchantment, essentially, is the possibility of being captivated by the beautiful. But this is because enchantment is the desire of the soul.

But before we can be captivated, we must recapture the experience of enchantment; this is what this book is trying to enable us to do. Enchantment should be an essential part of our storynot the missing ingredient of life. Enchantment is what raises our life out of the mere drudgery of existence. Enchantment is beyond the mere definition of the word. Enchantment, as being captivated by the beautiful, deliberately defers the meaning. But this does not worry us. What we have in this book is a movement from start to finish, from beginning to end, in various stages (chapters), in which enchantment is held before us indirectly. This is the only way to approach it.

The medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides wrote a famous and now classic work of religious philosophy called