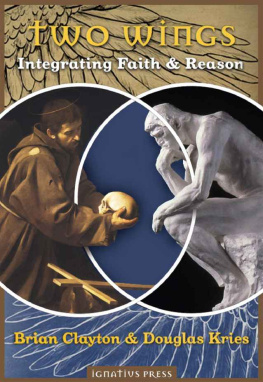

TWO WINGS

BRIAN CLAYTON and DOUGLAS KRIES

TWO WINGS

Integrating Faith and Reason

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the Revised Standard Version of the BibleSecond Catholic Edition (Ignatius Edition) Copyright 2006 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Cover art:

Front cover image [left]

Saint Francis in Prayer

Caravaggio (15711610)

Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica, Rome, Italy

Wikimedia Commons image

Front cover image [right]

The Thinker

August Rodin, 1880 plaster, 15 x 7 1/2 x 7 1/2

Gift of Samuel Hill, 1938.01.085

Collection of Maryhill Museum of Art

Goldendale, WA

Cover design by Carl E. Olson

2018 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-195-7 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-64229-032-5 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2017947385

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth: So begins Fides et ratio , the encyclical letter of Pope Saint John Paul II, published in 1998. It is the firm intention of this book to explain not simply that there are two such wings as John Paul indicated, but how these two wings are to be integrated so that they work together in the life of a single person. It is our conviction, based principally upon a great many years of teaching undergraduate university students in the United States, that such a book is desperately needed in our time. Instead of two wings working together to enable man to ascend to the contemplation of truth, what we are generally presented with todayif John Pauls analogy may be extendedis the claim that man must ascend to the truth with a single-winged soul. We are told that faith and reason are enemies rather than friends, incompatible adversaries between which one must choose. Reason, especially in the modern form of natural science, is said by some to be opposed to all believing; faith is said by others to be the only reliable way of acquiring truth since human reason is untrustworthy and, in addition, arrogant. Instead of two wings functioning in tandem, it is suggested that we must engage in a sort of self-mutilation, cutting off one wing and trying to fly with the other alone.

It is our contention that John Pauls advocacy for the existence and integrated functioning of the two wings of human experience is hardly new, and so we will rely heavily in this book on standard, classical Christian teachings about the relationship between faith and reason. At the same time, we are keenly aware that the standard and classical viewpoints must address both the genuine problems and honest questions of our time as well as the prejudices of the age. Thus, every effort will be made to show how the traditional positions relate to contemporary discussions. All of the arguments discussed in the following pages are capable of further refinement and almost infinite qualification. We do not write for experts, however, but for an audience of nonspecialists. Our goal is to provide such an audience with a single volume that will orient its readers with respect to the debates, thereby explaining how to avoid the common misunderstandings and pitfalls that cut off rather than promote further inquiry. We will offer overviews of the most important claims and counterclaims. Those who have the opportunity and inclination to go farther can consult the bibliography at the end of the volume as well as the online site associated with the book. We intend this volume to be the best beginning for studying all aspects of the relationship between faith and reason, but not the ending point for studying any of them.

A word should be added about the possible religious commitments of the books intended readership. Two Wings is written especially from a Catholic perspective, and one that is largely informed by the teachings of Augustine and of Thomas Aquinas. Nevertheless, we think that what is stated here is in accord with most forms of Christian faith, and, indeed, we think that the general principles established in the book would, with some paring and qualifying, even be transferrable to Judaism and Islam. As we go along, then, we will refer to Catholic authors and documents with some frequency, but we will also often comment in passing on how the claims being made would relate to the teachings of other Christians, as well as to Jews and to Muslims. The book contains much discussion of the rational or philosophical position called theism, and theism is, in outline at least, common to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. In any case, the fundamental question of our book may be stated hypothetically; that is, we will be asking, f one were to commit oneself both to theistic faith and to reasonable philosophy, how could one reconcile the two in a coherent view of reality? We will be making arguments that suggest that such a mutual commitment is possible, but our arguments seek to explain implications rather than to ask for final decisions in favor of Catholicism. Hence, while the book is written with Catholics first in mind, we think that theists of any sort should find it helpful.

This volume grows out of the long experience of its authors with the Faith and Reason Institute at Gonzaga University, which was formally established in 1999 in order to promote the sort of integrationist understanding of the relationship between the two wings of the human spirit envisioned by John Paul. One of the first fruits of the institute was the development of a course for Gonzaga University students titled simply Faith and Reason. The course was directed toward the needs of upper-division students working within Gonzagas core curriculum, which is to say that it sought to explain to students approaching graduation how faith and reason, whose study they had encountered earlier in their core curriculum, must be integrated into a comprehensive account of an educated person.

Development of the course brought together the contributions and talents of several members of the philosophy department at Gonzaga. Robert J. Spitzer, S.J., then president of the university, contributed his thoughts on the implications of contemporary astrophysics and cosmology for the faith-reason question as well as his reflections on the question of evil. Michael Tkacz, co-founder with Spitzer of the Institute, added his expertise in the medieval philosophy of natural science to the course. David Calhoun especially has offered his now extensive reflections on faith and evolutionary biology to the development of the Faith and Reason course.

While Spitzer, Tkacz, and Calhoun all taught the Faith and Reason course in its earlier days, the two members of the Gonzaga philosophy department who have continued to develop it and, indeed, still teach it are Brian Clayton and Douglas Kries, the authors of this book. Clayton, the current director of the Faith and Reason Institute, has brought to the course his wide-ranging reading in the analytic philosophical traditions understanding of the philosophy of religion. Kries interests lie primarily in the relationship of faith to moral and political philosophy.

In addition to developing its course of classroom study for students, the Faith and Reason Institute has hosted several conferences and speakers. The reflections of these thinkers on the questions surrounding the faith-reason debate have in turn stimulated the thinking of the philosophers just mentioned and have thereby indirectly affected the development of the Faith and Reason course. We will not attempt a complete enumeration of all who have contributed in this way, but particularly helpful have been the remarks of William E. Carroll, now of Oxford University, and Stephen M. Barr, of the Bartol Research Institute at the University of Delaware. The thoughtful contributions of Eric Kincannon, Hugh Lefcort, and Richard McClelland, of the physics, biology, and philosophy departments, respectively, at Gonzaga University, must also be acknowledged with gratitude. One of Brian Claytons daughters-in-iaw, Rene Towler Clayton, supplied the drawings of the blind people and the elephant in chapter 14 and the illustration of the Doppler effect in chapter 16. Finally, the support of Bernard J. Coughlin, S.J., bestowed especially through the Coughlin Chair in Christian Philosophy at Gonzaga, has been of great assistance to this effort, particularly to Professor Kries.

Next page