T hese collections are drawn, with permission, from a variety of sources: The Sugarcreek Budget , Proverbs of the Pennsylvania Germans by Dr.

Edwin Miller Fogel, the Pennsylvania German Dictionary by C. Richard Beam, and the sayings and adages I grew up hearing from my grandfathers Old Order German Baptist Brethren family. My grandfatherwe called him Deardadwas famous for pointing out to me with a frown that young folks should use their ears and not their mouths. Another saying I grew up hearing was, Choose your love and love your choice. That one belongs to my mother.

Introduction

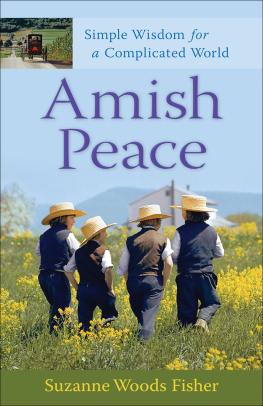

The Amish in Their Own Words M ost every culture has proverbs that are unique to it.

Whether called maxims, bromides, truisms, idioms, expressions, sayings, or just an old saw, proverbs are small, concentrated packages that let us peek into the window of a peoples values and beliefs. They give us insight into a culture, its faith, folklore, history, language, mentality, psychology, worldview, and values. These pithy sayings are not meant to be universal truths. They contain general observations and experiences of humankind, including lifes multifaceted contradictions. Proverbs, radio Bible teacher J. Vernon McGee once said, are short sentences drawn from long experience.

The ancient Eastern worldEgypt, Greece, China, and Indiais thought to be the home of proverbs, dating back to collections from as early as 2500 BC. King Solomon, who reigned in the tenth century BC, gathered many of them from other sources as well as edited and authored others. Over five hundred were compiled into the book of Proverbs in the Bible. Proverbs were used in monasteries to teach novices Latin. Often colorfully phrased, at times even musical in pronunciation, proverbs served as teaching tools for illiterate populations that relied on oral tradition. Interestingly, the proverbs have played a surprisingly prominent role in the speech of the Pennsylvania Germans, which includesthough isnt limited tothe Amish.

It is natural that the Pennsylvania Germans should use the proverb extensively, writes Dr. Edwin Miller Fogel in his book Proverbs of the Pennsylvania Germans , because of the fondness of the Germanic peoples for this form of expression. The proverbs are the very bone and sinew of the dialect. The ones that are common in the community are most likely in the oral tradition, says Dr. Donald B. Kraybill, senior fellow at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania.

Not particularly Amish, but part of the broader rural tradition of the area. The Pennsylvania Deitsch dialect (which is called Penn Dutch, though it has no relationship to Holland) originated in the Palatinate area of Germany over four hundred years ago and was brought to Pennsylvania in the 1700s with a wave of immigrants: Lutherans, Mennonites, Moravians, Amish, German Brethren, and German Reformed. Penn Dutch was, and is, an oral language; even today, people from different states can understand one another since the language has remained close to its origins. Most of what they [German immigrants] knew, they brought here from the Old World, explains C. Richard Beam, retired full professor of German at Millersville University. The proverbs were an integral part of Pennsylvania German culture.

The further back you go, the richer the language. The cleverness of a proverb, though, can be lost in translation. Heres an example: Wer gut Fuddert, daer gut Buddert . Good feed, much butter. Heres one that comes through a little smoother: Bariye macht Sarige . Borrowing makes sorrowing.

Beam worries that the language has been watered down and diluted over this last century, as the external culture has crowded out its rich heritage. Raised in Pennsylvania, Beam says that all four of his grandparents spoke Deitsch as their first language. We spent time with aunts and uncles and grandparents. That led to a richness of the culture, a preservation of the language. This was prior to radio and television. Beam is now 84 years old.

Theres a saying I was raised with: Every time the sheep bleats, it loseth a mouthful. That applies directly to the culture today. The dialect is losing words, he says. Language doesnt stand still. Today, only the Old Order Amish and the Old Order Mennonites have retained Deitsch as their first language. The Old Order Amish is a society that does not permit higher education.

Theirs is a culture learned from the simplicity of their ancestors lifestyles, and the Amish value this heritage. This simple lifestyle, passed virtually unchanged through the generations, provides an ideal base for the continual use of proverbs. Within the last century, the use of proverbs in modern American society may have diminished, but not so for the Amish. In fact, the opposite is happening. The Sugarcreek Budget is a weekly newspaper for the Amish-Mennonite community that began in 1890. Scribes from all over the world send in a weekly letter to the Ohio headquarters.

At the end of most letters, a proverb is added, like a benediction. The trend began about five to eight years ago, explains editor Fannie Erb-Miller. We started to allow a saying on the end of a scribes letter, and then it just caught on. Now, almost all of the letters have one. Early on, letters didnt include them. Mostly, theyre sayings that pass from generation to generation.

The proverbs are very relevant. They can speak to you. They can hit you. The proverbs in this book, like all proverbs, come from many sourcesmost of them anonymous and all of them difficult to trace. It is not unusual to find the same proverb in many variants. 22:6 KJV). 22:6 KJV).

God plays a prominent role in Amish proverbs, as does nature: weather and seasons, agriculture and animals. In our modern world, the rural savvy may seem outdated. But look a little deeper. The proverbs are every bit as relevant in the year 2012 as they were in 1712: Der alt Bull blarrt als noch means The old bull keeps on bellowing, or to give it a twenty-first-century twist, The old scandal will not die down. These sayings and proverbs, dear to the Amish, can help the English (non-Amish) better understand them. For example, here are two proverbs that reveal how the Amish value the virtue of patience: Only when a squirrel buries and forgets an acorn can a new oak tree come forth, and Adopt the pace of nature; her secret is patience.