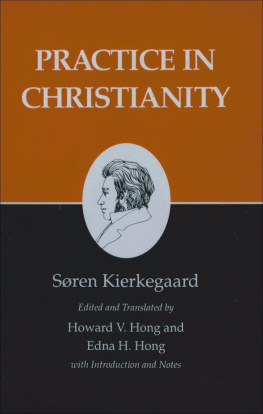

Kierkegaard

A Christian Missionary to Christians

Mark A. Tietjen

Foreword by Merold Westphal

InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

2016 by Mark A. Tietjen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Pressis the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org .

Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

While any stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information may have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Portions of chapter three were published in Mark A. Tietjen and C. Stephen Evans, Kierkegaard as a Christian Psychologist, Journal of Psychology and Christianity 30, no. 4 (2011): 274-83. Those portions have been either adapted or reprinted by permission.

Cover design: Cindy Kiple

Images:Corbis

ISBN 978-0-8308-9951-7 (digital)

ISBN 978-0-8308-4097-7 (print)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tietjen, Mark A., author.

Title: Kierkegaard : a Christian missionary to Christians / Mark A. Tietjen ;

foreword by Merold Westphal.

Description: Downers Grove : InterVarsity Press, 2016. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050886 (print) | LCCN 2016001402 (ebook) | ISBN

9780830840977 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780830899517 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Kierkegaard, Sren, 1813-1855.

Classification: LCC BX4827.K5 T57 2016 (print) | LCC BX4827.K5 (ebook) | DDC

230/.044092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050886

To Amy

Contents

Foreword

Merold Westphal

Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Emeritus Fordham University

T HIS IS NOT MARK TIETJENS FIRST BOOK ON KIERKEGAARD. In an earlier volume he offered an interpretation of Kierkegaards writings that directly challenged a type of reading that in recent years has become very popular among some academics. It can be called deconstructive. The basic idea is that partly because of the very nature of language and partly because of Kierkegaards literary style and tactics, his writings make no substantive claim on our belief and behavior; they rather teach us that every teaching undermines itself in ambiguity and undecidability. Mark made a compelling critique of such readings. It was an important contribution to Kierkegaard scholarship, appropriately published by a university press.

The present volume has a different purpose and is addressed to a different audience: those who are not academics, or at least not philosophers, or at least not Kierkegaard scholars. The intended audience is Christians who might benefit from hearing Kierkegaard presented as a missionary to Christians even if they be nonacademics, academics who are not philosophers or philosophers who are not Kierkegaard scholars.

Kierkegaards writings conclude with a series of polemical pamphlets that have come to be known as his attack upon Christendom, though I find this critique present from his earliest publications on. His complaint is not that the churches are not sufficiently orthodox but that they make being a Christian too easy, virtually automatic (if one happens not to be a Jew). They have, in his view, cheapened grace. So, with a wicked twinkle in his eye, he famously says that while everyone else is trying to make it easier to become a Christian, he will devote himself to making it harder. I will return to this theme.

Kierkegaards writings are very diverse in style, subject matter and purpose. I like to think of them as like the stanzas of a hymn such as, say, Rock of Ages. Each has its own task, making a different point or a similar point in a different way. But together they make a richly diverse yet coherent whole. Or, to use a different metaphor, each text is like one facet of a beautiful diamond whose oneness is enhanced and not compromised by its manyness. Kierkegaard insisted that serious interpretations of his work take the whole of his authorship into account. Happily, Mark roams gracefully and perceptively throughout the extensive corpus.

There is another plurality in Kierkegaards authorship that calls for a different metaphor. Mark tells us, importantly, that Kierkegaard is a philosopher, a theologian, a psychologist, a prophet and a poet. But these are not sequential, like stanzas, or spatially separate, like facets; they are simultaneous. A chocolate cake is a better image here. You dont first eat the flour and then the chocolate. You dont have eggs here and butter there. They are mixed together so that with every bite you eat flour and chocolate and butter and eggs and who knows what else.

Kierkegaard tells us, in retrospect, that he is a religious author, more specifically a Christian author. He insists that I am and was a religious author, that my whole authorship pertains to Christianity, to the issue: becoming a Christian, with direct and indirect polemical aim at that enormous illusion, Christendom (PV 23; cf. 8, 12). So he is a theologian.

At the same time he is a philosopher, and that in two senses. He engages the thought of important philosophers, especially Hegel and Plato, and he insists on careful conceptual analysis so that, for example, we do not conflate commanded neighbor love with spontaneous and preferential loves such as erotic love and friendship.

At the same time he is a psychologist in the sense of exploring what it means to be a self and how selfhood is not a fait accompli, an accomplished, presumably irreversible deed or fact,

At the same time he is a poet. For him one of the most important aesthetic values is the interesting. Through such literary devices as narrative, parable, satire, irony and pseudonymity, he sneaks up on the reader with substantial theological, philosophical and psychological claims. Just as with the help of the dialogue form Plato is more fun to read (and easier) than Aristotle, so Kierkegaard is more fun to read (and easier) than his nemesis, Hegel.

At the same time, finally, he is a prophetin the biblical sense of the terma social critic who exposes the discrepancy between the moral and religious values a people profess and their daily practice. Early prophets did indeed foretell the loss of national independence that would occur if the people did not change their ways; but their predictions were not those of a psychic satisfying curiosity about the future. They were dire warnings of the drastic consequences of continuing in idolatry and the oppression of the poor.

For this dimension of his work, Kierkegaard took Socrates, the gadfly (stinging pest), as his model. He conversed with the best and the brightest of Athens, who were complacently content that their practices were grounded in a solid knowledge of the truth. Through his sharp (not especially gentlemanly) questions, Socrates showed that they didnt know what they were talking about. Perhaps Kierkegaard does not explicitly take the biblical prophets as his model because, while they were able to say, Thus says the Lord, he insisted that he spoke without authority.