Confucianism

A SHORT INTRODUCTION

Confucianism

A SHORT INTRODUCTION

John H. and Evelyn Nagai Berthrong

CONFUCIANISM: A SHORT INTRODUCTION

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2014

First published by Oneworld Publications, 2000

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

John H. Berthrong and Evelyn N. Berthrong 2000

All rights reserved.

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781851682362

eISBN 9781780746739

Cover design by Design Deluxe

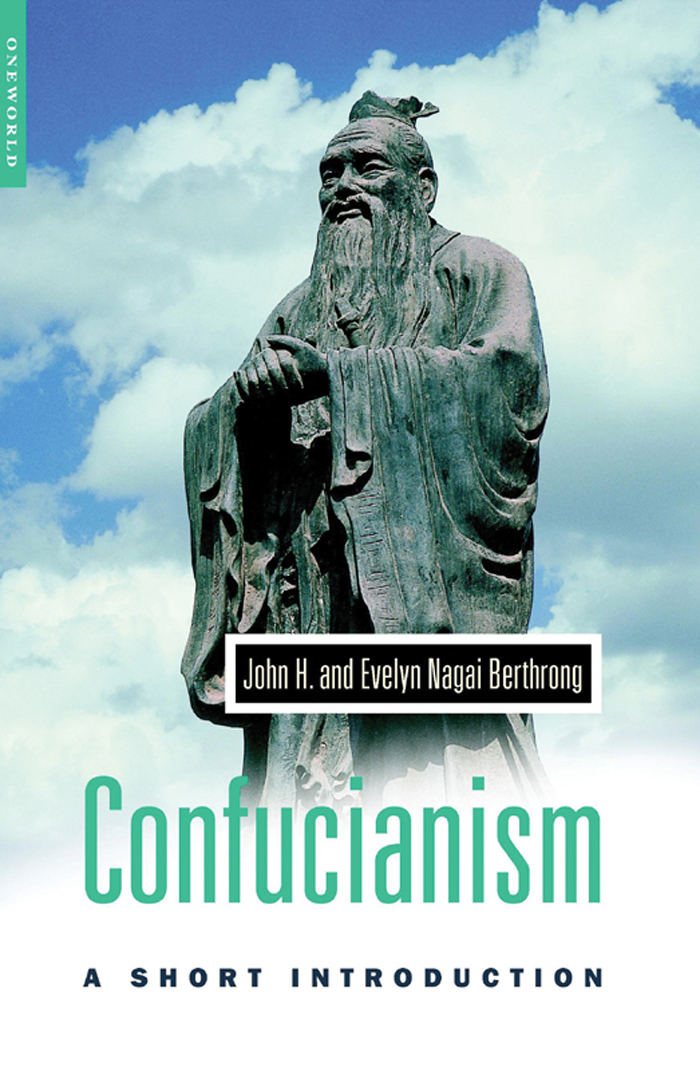

Cover image of statue of Confucius Ann and Bury Peerless Picture Library

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

S ometimes small books have many friends. It is certainly the case for this introduction to the Confucian tradition. There has been a renaissance of studies of various aspects of the Confucian tradition that now stretches back at least four decades in North America and Europe. As we view East Asia, we must remember the foundational work of a small group of Chinese scholars now known as the New Confucians. Their reflections began in the 1920s and 1930s when times seemed darkest for anyone seriously interested in the study of or commitment to Confucianism as a philosophic tradition and way of life. Along with this early cohort of the New Confucian movement, we must also acknowledge the fact that serious scholars have continued the study of Confucianism in Korea and Japan throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. It is upon the labors of these last four generations that this work is built.

There are more proximate groups of people we need to thank. We think especially of Wm. Theodore de Bary of Columbia University. He has provided continuous active leadership ever since 1950. Many of his students have gone on to become major scholars in the field as well. On the Chinese side we would be remiss not to mention teachers and colleagues such as Tu Weiming, Julia Ching, Cheng Chung-ying, and Liu Shu-hsien. In this group we also want to thank the Neo-Confucian Seminar of Columbia University. The Seminar has provided a venue over the years to test our ideas and to profit from the research of friends and colleagues from around the world.

Over the last five years a number of people have provided even more stimulation for this work, even if they were unaware of the role they would play in the writing of it. Our colleagues in the Confucian Studies Group of the American Academy of Religion and the Society for the Study of Chinese Religion (often active at the Association for Asian Studies) have helped to promote the cause of Confucian studies within the larger world of North America. Sometimes we even have the pleasure of welcoming friends from Asia and Europe. We add our thanks to colleagues such as Joseph Adler, Mary Evelyn Tucker, Deborah Summer, John Chaffee, Zheng Jiadong, John Henderson, Michael Nylan, P. J. Ivanhoe, Peter Bol, Zhang Longxi, Irene Bloom, Hoyt Tillman, Rodney Taylor, Lisa Raphals, Hal Roth, Peter Nosco, Janine Sawada, Roger Ames, David Hall, Chen Lai, Michael Kalton, Lionel Jensen, Thomas H. C. Lee, Mark Setton, and Philip Clart. We hope that all of these named and unnamed colleagues will recognize the good they have contributed and not notice where we have misused their diverse achievements.

At Boston University we thank Robert C. Neville, Joseph Fewsmith, Livia Kohn, David Eckel, Merle Goldman, Ray Hart, John Clayton, Peter Berger, Adam Seligman, Robert Weller, Chung Chai-sik, Wesley Wildman, and Jensine Andresen for their interest, correction, and conversation. We also want to thank our research assistant, Mr. He Xiang, and Ms. Tracy Deveau, a perfect administrative assistant. The university administration of Dennis Berkey, Provost, and Jon Westling, President, has provided generous support for and appreciation of scholarship and research. This support included a leave in 1999 that was instrumental in finishing the project.

Even closer to home, we need to thank our son, Sean Berthrong, and our good friend Loretta Cubberly, who could always be counted upon to look after the house as we traveled around the country and the world.

Our colleagues at Oneworld Publications, especially Victoria Warner, have given us constant encouragement all along the way. We owe an immense debt of gratitude to them for allowing us to write a different kind of introduction to a great philosophic and religious tradition.

Plate 1 Guardian figures at the entrance to a temple in the Forest of Confucius, Qufu, the ancestral burial ground of the Kong family. The Forest includes a tumulus believed to have once held the remains of Confucius himself. Photo: Evelyn Berthrong.

INTRODUCTORY REFLECTIONS

INTRODUCING CONFUCIAN LIVES

C onfucianism has been and still is a vast, interconnected system of philosophies, ideas, rituals, practices, and habits of the heart that informs the lives of countless people in East Asia and now the whole inhabited world. Although known in the West mostly as a philosophic movement, Confucianism is better understood as a compelling assemblage of interlocking forms of life for generations of men and women in East Asia that encompassed all the possible domains of human concern. Confucianism, at various times and places, was a primordial religious sensibility and praxis; a philosophic exploration of the cosmos; an ethical system; an educational program; a complex of family and community rituals; dedication to government service; aesthetic criticism; a philosophy of history; the debates of economic reformers; the intellectual background for poets and painters; and much more. For instance, we owe to Confucians in East Asia the most extensive written historical record for any human civilization from its beginning down to today. We also owe Confucians medical prescriptions, vast hydraulic works, bonsai and wonderful gardens.

In China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, Confucians historically created worldviews, ways of life, and deeply shared cultural orientations and sensibilities that are still alive today. Confucians paid attention to art, morality, religion, family life, science, philosophy, government, and the economy. In short, Confucians were profoundly concerned with all aspects of human life. Moreover, Confucians played a distinguished role in creating innovative reflections and achievements in all dimensions and endeavors of human life. The collected modalities form the tapestry of civilization. The Confucians have always had a complex, holistic and organized view of human life, nature, character, thought, and conduct. It is also a fascinating question to explore how Confucians understood their culture, or Dao/Way as they called it, over long centuries and vast spaces.

We have created an iconic (and fictional) Confucian husband and wife, Dr. and Mrs. Li, living in the famous, cultivated, and beautiful city of Suzhou (situated in central China just south of the great Yangtze river) in 1685. The Lis are what is called an ideal type or prototype, a generalized portrait of what the lives of a late imperial Confucian couple might have been. We have chosen this method in order to make the point that Confucianism is so much more than the history of ideas. It was and is a complicated pattern of human life, which affected men and women differently. Furthermore, how they understood Confucianism depended on their social position: elite couples like the Lis could be self-consciously Confucian whereas a poor peasant family in the southeast of China might only have the faintest understanding of the teaching of the Confucian tradition. However, as we shall see, Confucianism touched the lives of all the peoples in East Asia. Of course, it formed the lives of such a prototypical couple as Dr. and Mrs. Li more closely and more richly in 1685 than anyone else in Chinese society. It is because of the richness and influence of such elite Confucian culture at the end of its grand imperial career that we have dared to resort to such a narrative strategy.