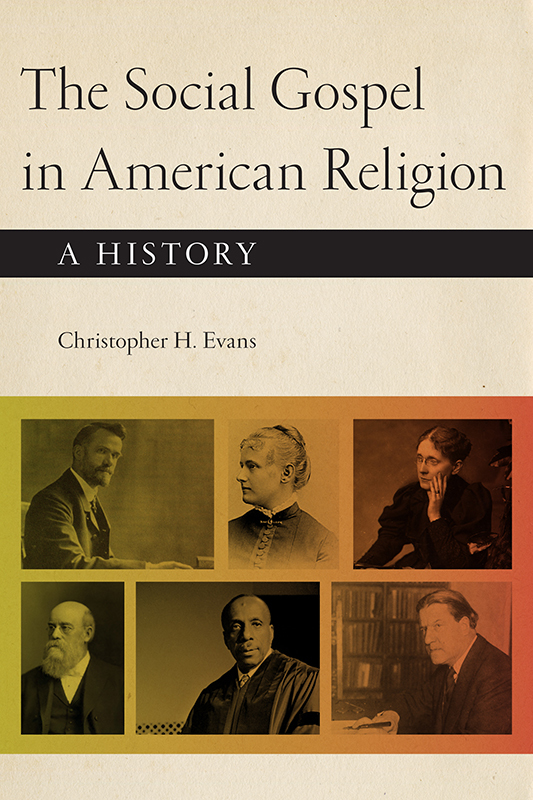

The Social Gospel in American Religion

The Social Gospel in American Religion

A History

Christopher H. Evans

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-6953-4 (hardback)

ISBN : 978-1-4798-8857-3 (paperback)

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

I am indebted to many individuals who enabled this book to be written. Above all, I am grateful to Jennifer Hammer, my editor at New York University Press, for her support and encouragement of this project. Jennifers critique of earlier versions of this manuscript and keen editorial eye challenged me to improve the book while inspiring me onward in the task of writing. I couldnt ask for a better colleague in this endeavor.

A number of people read and commented on various parts of the manuscript. Above all, I am thankful to the amazing scholars in the Boston Historians of American Religion Group, with particular gratitude to Jon Roberts, Peggy Bendroth, Cliff Putney, Chris Beneke, M. J. Farrelly, Patricia Appelbaum, Jess Parr, and Roberta Wollons for their helpful comments on various chapter drafts. I was fortunate to receive invaluable research assistance from two outstanding graduate students at Boston University, Laura Chevalier and Matthew Preston. This book also reflects my gratitude for my current and former students at Boston University and Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School. Their questions and engagement with me over the years have inspired a great deal of my scholarship and make me grateful for the opportunities that Ive had in my career as a teacher. As always, I am thankful to Robin, Peter, and Andrew for the ways that they have indulged my passion for history.

In 1958 Martin Luther King Jr. acknowledged his intellectual debt to a movement in American religious history commonly called the social gospel. Citing the impact of the early twentieth-century church leader Walter Rauschenbusch, King noted that Rauschenbuschs social gospel had pushed Christian theology beyond a concern for individual salvation to engage questions of social justice. At its core, religious faith needed to address questions of systemic political change. It has been my conviction ever since reading Rauschenbusch that any religion which professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the social and economic conditions that scar the soul, is a spiritually moribund religion only waiting for the day to be buried.

In 1996 another religious activist concurred with King, contending that religion had an implicit mission to change the social fabric of modern life. This author affirmed that Rauschenbusch and King were part of a wider history of American religious political engagement, the story of slumbering faith awakening from the pews and flowing into school board meetings, courtrooms, slums, and state capitols. What is perhaps surprising is that this second activist was not a theological liberal but the longtime head of the conservative-based Christian Coalition, Ralph Reed.

Reeds gloss of American religious history ignored important nuances in historians definitions of the social gospel. At the same time, the fact that Reed sought to recast a religious heritage with deep-seated connections to theological and political liberalism is significant. Reeds identification of the Christian Coalition with the social gospel is indicative of how broadly definedand historically contestedthe movement has been in American history.

Largely associated with late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American Protestantism, the social gospel was a religious movement that applied a liberal theology to a range of social reform measures that would become associated with the political left. However, as Ralph Reeds uncritical use of this term suggests, the social gospel is a somewhat elastic concept, often used broadly to denote any sort of religious engagement with social issues. To trace the rise of the social gospel in American religious history and its legacy in the twentieth century is the purpose of this book.

Defining and Interpreting the Social Gospel

While many scholars date the social gospels origin and apex roughly to the Progressive Era of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they have long debated precise definitions of the social gospel, what persons/groups fall under the rubric of this term, and when this tradition ended. Mathewss phrase the application of the teaching of Jesus illustrates how certain religious leaders have interpreted the social gospel as a unique model of applied religion. Specifically, Mathews noted that the social gospel modeled a modern tradition of religious ethics. There was nothing particularly novel about understanding a religious tradition, like Christianity, through ethical engagement. Yet the social gospel embodied a new understanding of social engagement that challenged earlier suppositions coming out of previous religious movements in America, especially in the nations Protestant churches.

As a way to orient the reader, I offer a definition of the social gospel that will anchor the discussion in this book: The social gospel was an offshoot of theological liberalism that strove to apply a progressive theological vision to engage American social, political, and economic structures.

The social gospels religious idealism developed out of the movements unique origins in nineteenth-century American Protestantism. Although this books narrative seeks to broaden the religious base for understanding the social gospel as a theological tradition, it pays close attention to how this movement emerged out of distinctive currents of evangelical and liberal Protestantism. This intersection helped to fuse earlier visions of Protestantisms mission to an emerging late nineteenth-century belief that equated Christian teachings with specific social-economic reform efforts. Part of this books goal is to analyze what many scholars have identified as the classic social gospel era, corresponding roughly from the final quarter of the nineteenth century through the first quarter of the twentieth century. In the context of postCivil War America, many religious leaders were coming to terms with a nation that was coping with immigration, industrialization, urbanization, and new manifestations of institutional racism. Those who embraced what became known as the social gospel were alarmed by the social inequalities that existed in American society and increasingly challenged taken-for-granted assumptions about the inherent goodness of laissez-faire capitalism For some scholars, the social gospel has been interpreted as the religious wing of the Progressive Era, in that its major leaders embraced a long-standing belief that the nations moral-ethical fabric depended upon the strength of its religiouschiefly Protestantinstitutions.

Next page