This edition first published in 2014 by Weiser Books, an imprint of

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

With offices at:

665 Third Street, Suite 400

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.redwheelweiser.com

Sign up for our newsletter and special offers by going to www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter.

Copyright 1998. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages. Originally published in 1998 as The Ecstasy of Enlightenment by Weiser Books, ISBN: 1-57863-027-4.

ISBN: 978-1-57863-568-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

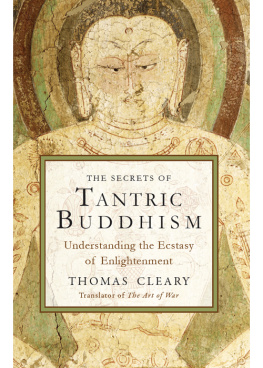

Cover Design by Jim Warner

Cover Image: Vairochana Buddha, from Balawaste, 7th-8th century (wall painting), Indian School / National Museum of India, New Delhi, India / The Bridgeman Art Library

Interior design by Frame25 Productions

Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed in Canada

MAR

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

This work is dedicated to the memory of the honorable Abdul Aziz, former Senior Advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh.

Exemplary people understand things in terms of justice.

Analects of Confucius

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF TANTRIC BUDDHISM

Tantrism is widely known as the most elaborate and colorful form of Buddhism. It is considered by many to be the most sophisticated form of Buddhism, while viewed by some as the most degenerate. It is certainly the most controversial. In modern times, Tantrism is the principal mode of Buddhism in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, Ladakh, and Mongolia, as well as a major tradition of Buddhism in Japan.

In the past, Tantric Buddhism was also practiced in India and China, and probably in what are now Afghanistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Tantrism was absorbed by Taoism in China, by Hinduism and Sufism in India, by Sufism in Afghanistan, and by Hinduism and Sufism in Indonesia and Malaysia.

The main source of Tantric Buddhism, from which the movement emanated over such a vast area of Asia, was the extraordinarily rich cultural basin of old Bengal. Now comprising Bangladesh and part of India, the Bengal region was just east of Magadha, the original homeland of Buddhism. A major center of trade since ancient times, the Bengali cultural basin was connected with many different regions, including the Greek and Roman spheres, by both land and sea routes. It is one of the oldest strongholds of Buddhism.

Numerous ethnic and linguistic groups have inhabited the region of old Bengal since ancient times, and many more were to immigrate there over the ages. This process resulted in a diverse population, with many different traditions of thought and behavior. When Bengal was eventually integrated into Aryan and Muslim polities, this endemic cultural pluralism survived, engendering a spirit of religious tolerance that withstood even the most violent political agitations and pressures. There can hardly be any doubt that Tantrism played a major role in this aspect of Bengali cultural resilience. The Buddhist presence in Bengal was very old and well established when Tantrism emerged as a distinct movement. According to the famous seventh-century Chinese pilgrim Hsuan-tsang, Gautama Buddha, himself, visited several places in Bengal and taught there. While there is no concrete corroboration of this claim, it cannot be considered unlikely.

There is, after all, no surviving concrete contemporaneous corroboration of anything about Buddhism in the lifetime of Buddha himself. There was no Buddhist art in Buddha's time, and no Buddhist literature. But it is well established that Buddha did travel around during nearly fifty years of teaching activity, and Bengal was a highly accessible neighbor to Buddha's native Magadha. The linguistic differences between the majority languages of Magadha and Bengal were at most dialectical.

Even if Gautama Buddha himself did not visit Bengal personally, given the status of Bengal as a trade center, and the known support for Buddhism among the merchant class in India, it would seem reasonable to consider it likely that Buddhism did, indeed, enter the Bengali region from very early times.

The first concrete monumental evidence of Buddhist presence in Bengal appears to be a stone plaque inscription assigned to the Maurya period (c. 325183 B.C.E.). Two votive inscriptions on the railing of a Buddhist stupa are dated from the second century B.C.E. According to the Buddhist historian Taranatha, Buddhist communities were established in east Bengal from the time of the great Maurya emperor Ashoka (c. 273232 B.C.E.).

Ashoka united nearly all of India, including Baluchistan and Afghanistan, under the Maurya rule. He is known to have sent Buddhist missionaries all over the Indian subcontinent, as far south as Sri Lanka, and as far west as Anatolia, Syria, Egypt, and Greece. Considering the fact that Buddhism is even believed to have reached as far as Ireland at this time, via the sea route from the Mediterranean, it is hardly thinkable that Bengal would not have been within the scope of this vast missionary effort.

Early Buddhist literature, although of uncertain date because of its derivation from oral tradition, mentions Bengal as a center of maritime trade and of Buddhist activity from olden times. The Mahavamsa refers to a prince named Vijaya who made a voyage from Bengal to Sri Lanka with a retinue of seven hundred. The Mahaniddesa acknowledges Bengal as an important center of overseas trade, and so does the remarkable Milindapanho, Questions of Menander, which is believed to record conversations of a Buddhist elder with a Graeco-Buddhist king. It is well known that Buddhism spread through Central Asia and into China along the Silk Road trade routes, and there can hardly be any doubt that knowledge of Buddhism also went along with other forms of international communication in other regions as well.

The dialogue with Menander would have taken place in the West, on the other side of the Indian subcontinent, where the empire of Alexander the Great collided with that of Chandragupta Maurya. Mention in this context would reflect the farflung fame of Bengal in those ancient times. The Divyavadana also includes north Bengal within the domain of the Buddhist majjimadesa or Middle Country, the classical homeland of Buddhism.

The reputation of old Bengali Buddhism becomes even clearer in the early centuries of the common era. An inscription dated back to the second or third century includes Vanga, in the heartland of Bengal, among the countries that gladdened the hearts of the teachers of the Buddhist Sthaviravada, or School of the Elders. Other countries mentioned include Kashmir in the north, Gandhara (now in Afghanistan and Pakistan) in the west, China in the north and east, and Sri Lanka in the south, suggesting the immensity of the realm of Buddhist culture within which Bengal was included as a major center.

A seventh-century Chinese pilgrim, I-ch'ing, even states that a temple for Chinese Buddhists was established in Bengal under royal patronage in the second century. As this was a time when Buddhism was still in an early phase of establishment in China, this would . indicate the international importance of old Bengal as a primary source of the teaching.

Next page

![Krishna Dharma - Mahabharata: [the greatest spiritual epic of all time]](/uploads/posts/book/213378/thumbs/krishna-dharma-mahabharata-the-greatest.jpg)