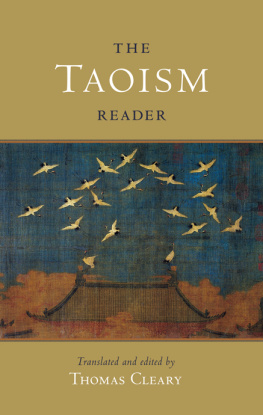

ABOUT THE BOOK

The dynamic relationship between the individual and society has been a central concern of Taoism from its ancient beginningswhich is perhaps why certain Taoist classics, like Sun Tzus Art of War, are so often consulted these days for leadership advice. This anthology presents a wide range of texts revealing the processes of integrating personal spirituality with social responsibility central to Taoist tradition across the centuries and throughout the schools. There are a wealth of approaches to life in the world presented here, but at the heart of each is an understanding that even a mystic must be socially responsible and that self-cultivation is primary preparation for anyone called to lead.

THOMAS CLEARY holds a PhD in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University and a JD from the University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. He is the translator of over fifty volumes of Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and Islamic texts from Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Pali, and Arabic.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

THE WAY

OF THE WORLD

Readings in Chinese Philosophy

TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY

THOMAS CLEARY

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2011

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2009 by Thomas Cleary

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The way of the world: readings in Chinese philosophy / translated and edited by Thomas Cleary.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2315-0

ISBN 978-1-59030-738-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Philosophy, Taoist. I. Cleary, Thomas F., 1949 II. Title: Readings in Chinese philosophy.

B162.7.W53 2009

181.114dc22

2009010616

CONTENTS

Once referred to in terms of a Hundred Schools, the colorful spectrum of Chinese philosophy, however diverse in its attitudes and ideas, is typically centered on concrete problems of human life, from the personal to the political, as an interlinking causal chain or circle. A Chinese philosophy is therefore typically presented as something to be practiced, a guiding principle or path to be followed, and so is referred to as a Way.

Sometimes a Way is named by or for a founding figure, historical or legendary; sometimes a Way is defined in reference to a salient conceptual context or practical method. Expressions such as the Way of Nature, the Way of Humanity, the Way of Heaven, and even the Way of Demons thus emerged over time to describe different stages and schools of Chinese philosophy and practice, these terms appearing within the master works themselves as well as in descriptions by observers and analysts.

A great deal of ancient Chinese historical and philosophical literature was lost long ago through the ravages of warfare and the strategic destruction of books and scholars by the First Emperor of China in the third century B.C.E. Having united the warring Chinese states by military conquest, the First Emperor sought to unite the new empire culturally by erasing history and eliminating competing schools of political philosophy, and reducing government to administration of a mechanical rule of law enforced by a policy of deliberately disproportionate punishment that amounted to a program of state terror.

The regime of the first empire soon cracked and shattered under the weight of its own ambitions and oppressions, to be supplanted by a new dynasty, the Han. Initially implementing more relaxed public policies traditionally associated with so-called Huang-Lao or Taoist philosophy, the ruling house of Han sponsored reconstruction of traditional Chinese culture, including an attempt to retrieve and organize pre-imperial literature.

This collective concentration appears to have played an important part in the hold on the Chinese empire maintained by the ruling house of Han for more than four centuries, even through calamitous civil wars and a major coup dtat midway through its tenure. So central was this era to the formation of the cultural identity of the Chinese empire that the majority nationality in China today is still referred to by the name of this dynasty, as Han.

The Han reconstruction of ancient literature was faced with massive problems of wastage and confusion caused by human destruction and natural decay. The radical reforms of the First Emperor had created a kind of cultural vacuum, an interruption of tradition that could never be completely bridged and was therefore patched with creativity and imagination. Consequently, there never has been a uniform interpretation of the classics among native scholars, even at the lexical level; many famous books are considered reconstructions, forgeries, or composites; and scholars differed among themselves in their categorizations of philosophers into specific schools of thought.

It was in this milieu that the term Daojia, typically anglicized as Taoism or Taoist, was coined by the famous historian Sima Qian (ca. 14586 B.C.E.) to refer to doctrines he describes in these terms:

The Daojia make peoples vital spirit unified, acting appropriately without formality, sufficing all people. As for their practical methods, based on the universal order of yin and yang, taking what is good in Confucianism and Moism, distilling the essences of logic and law, they move with the times, change in response to the concrete, establish customs and carry on business in any way appropriate. The instructions are simple and easy to practice; little is done, but with much effect.

The emphasis on adaptation, expressly including the ability to employ what is useful in other doctrines without emotional bias, enabled Taoism to manifest a multitude of forms over the centuries, and to maintain lines of communication through which other traditions absorbed Taoist teachings. Specific inclusion of Confucianism, Moism, logic, and law, moreover, indicates an understanding of Taoism as essentially pragmatic, innocent of the introverted, irrational, and antisocial attitudes occasionally attributed to it by the uninformed and the immature.

The present volume contains original translations of some of the earliest extant texts containing materials associated with the Daojia, accompanied by compositions of later times and a set of famous apocrypha. These works demonstrate different Taoist approaches to the practical dynamics involved in the relationship between the individual and society.

The first set of materials consists of four Taoist chapters from the mammoth collection Guanzi, or Master Guan, a very prestigious compendium of practical political philosophy. This work has been classified as Taoist, and also as Legalist. The four chapters presented here are called Inner Work, Mental Arts (I and II) and Purifying the Mind. Generally speaking, these tracts deal with self-government as at once an analogy and a practical prerequisite for leadership.

The writings are not generally believed to be original works of Guan Yiwu (725645 B.C.E.), under whose distinguished name the large and varied body of work Guanzi has been collected. Some commentary has also been formally internalized, suggesting successive authors, yet these four chapters appear to be among the earliest extant works of Taoist philosophy. A story of Master Guan is given in the later Taoist classic

Next page