ABOUT THE BOOK

Throughout Zen history, stories and anecdotes of Zen masters and their students have been used as teaching devices to exemplify the enlightened spirit. Unlike many of the baffling dialogues between Zen masters preserved in the koan literature, the stories retold here are penetratingly simple but with a richness and subtlety that make them worth reading again and again. This collection includes more than one hundred such storiesmany appearing here in English for the first timedrawn from a wide variety of sources and involving some of the best-known Zen masters, such as Hakuin, Bankei, and Shosan. Also presented are stories and anecdotes involving famous Zen artists and poets, such as Sengai and Basho.

THOMAS CLEARY holds a PhD in East Asian Languages and Civilizationsfrom Harvard University and a JD from the University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. He is the translator of over fifty volumes ofBuddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and Islamic texts from Sanskrit, Chinese,Japanese, Pali, and Arabic.

Sign up to receive weekly Zen teachings from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes.

Zen Antics

A Hundred Stories of Enlightenment

Translated and edited by

Thomas Cleary

Shambhala

Boston & London

2014

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1993 by Thomas Cleary

Cover art: Hotei Pointing at the Moon by Fugai Ekun. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, promised gift of Murray Smith. Reproduced by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cleary, Thomas F., 1949

Zen antics: 100 stories of enlightenment/translated from the Japanese by Thomas Cleary.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-83483-014-1

ISBN 0-87773-944-7 (acid-free paper)

1. Zen BuddhismAnecdotes. 2. Enlightenment (Zen Buddhism)

Anecdotes. I. Tide.

BQ9265.8.C54 1993 93-12213

294.344dc20 CIP

Contents

Zen Buddhism is a science of awakening the mind, an art of spiritual enlightenment. Once practiced throughout East Asia in a wide variety of forms by people from many cultures and walks of life, Zen is not a body of dogma but a way of clarifying and enchancing consciousness.

Zen is called a special transmission outside of doctrine, not defined by literal formulations, but directly pointing to the human mind for the perception of its essence and fulfillment of enlightenment. Anciently known as the school of the enlightened heart, the gateway to the source, and the unalloyed communication of mind by mind, Zen absorbed and pervaded the vast spectrum of Buddhist practices and teachings, while concentrating on the keys to their practical realization.

All Buddhist teachings are concerned with either or both of the two fundamental facets of Buddhism, self-help and helping others, wisdom and compassion. These two phases of Buddhism are carried out by means of practices implementing what are known as the six and ten perfections or transcendent ways.

The significance of these formats may be kept in mind by means of a play on the original Sanskrit word for the perfections, pramit, which literally means having reached the goal, or having gone beyond. In essence, the pramits may be called the parameters of Buddhism, the characteristic values underlying all Buddhist systems.

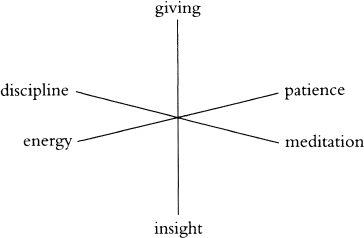

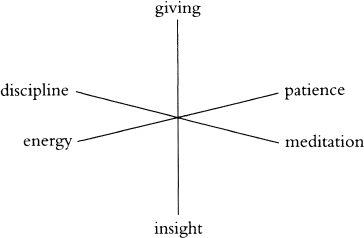

The phase of self-help in Buddhism is characterized by the six pramits of giving, discipline, patience, energy, meditation, and insight.

Three main kinds of giving are traditionally defined in Buddhism: giving material support; giving security; and giving education. Giving also means relinquishment, non-attachment.

There are also three main kinds of discipline traditionally defined: the discipline of restraining evil; the discipline of constructive virtue; and the discipline associated with concentration. Zen also teaches formless discipline of mind.

Many kinds of patience are practiced in Buddhism, including the patience involved in tolerating disdain and abuse; the patience involved in tolerating painful truths; and the patience needed to accept ultimate truth.

Energy refers to the perseverance and spiritual heroism needed to break through the boundaries of conditioning, free the mind from needless limitations of habit, and fulfill its potential.

Meditation is needed to gather and focus attention to a depth and degree sufficient to enable the practitioner to alter perception and experience of self and world at will. The science of meditation is elaborated and perfected to a rare degree in Buddhism, with innumerable methods designed to accommodate the needs of people of all sorts of potentials and capacities.

Insight commonly refers to a special kind of knowledge in Buddhism, a precognitive or intuitive sense of the essence of things, functioning spontaneously and instantaneously without the intervention of linear reasoning. This enables the whole mind to operate at a higher level of objectivity and integrity, freeing the individual from delusion.

There are countless variations on the practices of the six pramits, depending on the needs of the individual concerned. In every case, however, they have to be combined in order to produce the desired effect. Thus while the six pramits may be viewed as a series in some sense, they are more properly understood as a set, which may be depicted in a circle. In the early stages of practice, the six perfections may be viewed as functioning in complementary pairs.

Eventually the practices and realizations of each and every one of the six pramits integrate with those of all the others, complementing and perfecting them. In Zen lore, the opening of insight is often referred to as awakening or enlightenment, but this only signals a stage at which higher integration of the six pramits may commence in real experience, not the supreme perfect enlightenment of which Buddhist scriptures speak.

That supreme perfect enlightenment is realized through a more advanced program of ten pramits, which goes on to develop the capacity to attain not only sufficient enlightenment for oneself but the greater enlightenment to liberate others.

The ten pramits include the foregoing six, adding to them four higher perfections of increasing sophistication, known as skill in means, vowing, power, and knowledge.

Skill in means refers to the ability to devise and employ appropriate techniques to liberate and enlighten other people. Buddhism evolved countless such expedient means over the centuries in order to accommodate the needs and potentials of all sorts of individual and collective psychological types in every phase of human civilization.

Vowing, or commitment, is the use of directed will for the purpose of linking the individual consciousness with the totality of Buddhism, joining self-development and the welfare of others in an inseparable continuity. Many typical vows of welfare, liberation, and enlightenment are described in Buddhist literature, but all of them are based on the same fundamental principles.

Next page