Contents

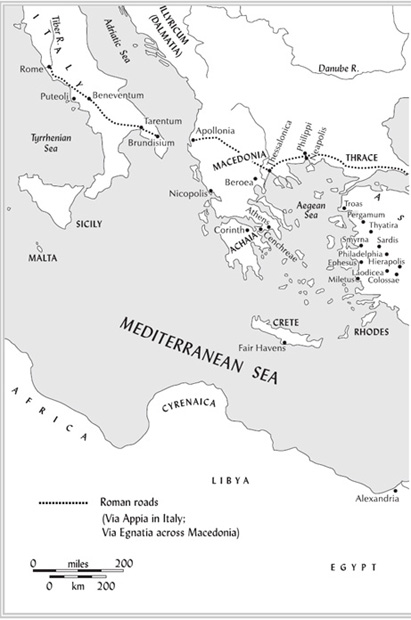

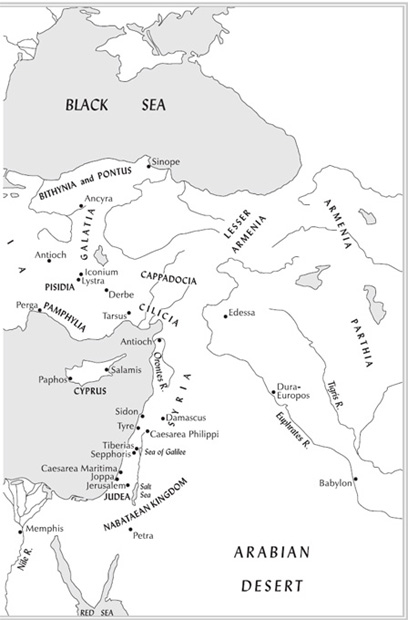

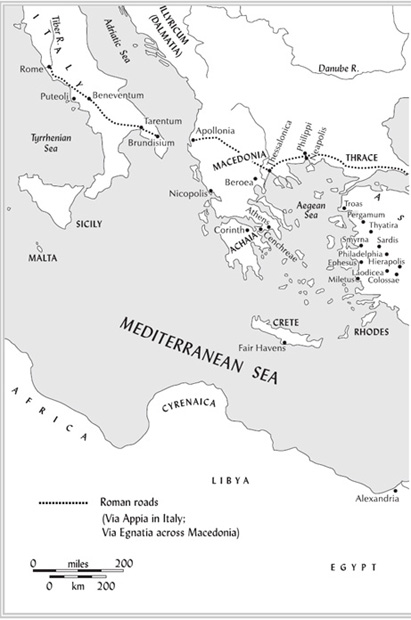

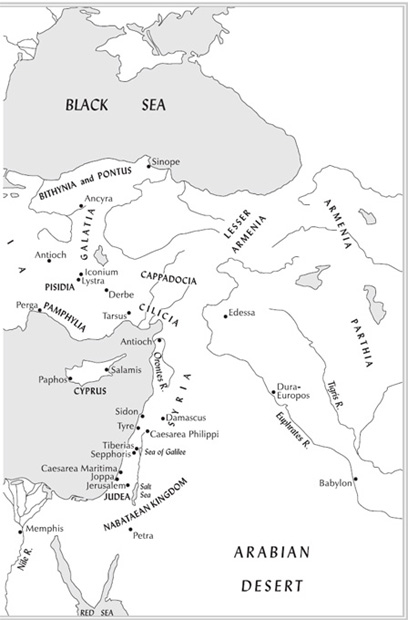

Map of the Mediterranean Basin in the

First Century, from Italy to Parthia

To My Teachers

List of Illustrations

1. The Mediterranean Basin in the First Century,

from Italy to Parthia

2. The Temple Mount During

the Second Temple Period

THE MEDITERRANEAN BASIN IN THE FIRST CENTURY, FROM ITALY TO PARTHIA

Foreword

This book completes a journey that began in 1967 when I was just shy of eighteen years old and traveling in the former Yugoslavia. One oppressively hot day, wandering around the seaside town of Dubrovnik, I ducked into the dark confines of a medieval church. It was cool inside and very still. Im not sure why, but I knew I was completely alone. I smelled the faint residue of incense, the musty aroma of damp stone. My steps echoed as I walked down the aisle between worn wooden pews, drawn to a frieze behind the altar depicting Christ on the cross. It was a typically medieval portrait; none of the gory details had been spared. The figures head in bluish stone was askew, lolling. Spikes were driven through palms and blood ran down the wrists and arms. The feet had been turned sideways and nailed through the ankles. The bent knees were contorted and looked particularly vulnerable, helpless. The figure was slumped, the body twisted and broken. I had a momentary but searing impression of agony; I was moved by the figures fragility in the face of a vast and violent universe, and I felt the crushing pain of our common mortality. But paradoxically, deep inside myself, I also felt the answering reverberations of something beyond pain, beyond despair. I turned and walked slowly out of the church and into the sunlight on cobbled streets. I was a kid, and the illumination was fleeting. I had better things to do than dwell on suffering and death. I bought a bottle of beer from a vendor near the harbor and sat drinking it, looking out over the blue Adriatic. Then I took a swim. My spiritual quest to that point had involved half-hearted attempts at Buddhist meditation. But the frieze and what it invoked germinated inside me. I couldnt shake it, and the Dubrovnik experience eventually led me to seek ordination.

Later I entered seminary and began to learn the techniques of biblical criticism. I was especially excited by how the study of ancient languages could yield insights into the original meanings of the texts, and I was drawn to academic research when I found that few scholars had examined the ancient literature of Judaism in Aramaic, the common language of the Jewish people in the first century that Jesus spoke. The Targums, paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible rendered in Aramaic, especially fascinated me. The Targums were part of the Torah on the lips, the oral version of Scripture that Jesus worked from, and they were different in important ways from the Hebrew texts. I sensed they were key to understanding what Jesus believed and taught. I knew that the priesthood would be a futile pursuit for me unless it was based upon the best possible knowledge about Jesus and the origins of the Christian faith. How could the Church fail to pursue the cultural and social background of Jesus? How could we as priests fail to ask what Jesus life had been like and how he had come to develop his extraordinary vision of God?

So alongside the priesthood I pursued a career as a scholar and teacher, learning Greek, Hebrew, and Latin (the stock in trade of New Testament scholarship), Aramaic to study the Targums, Coptic to study Gnostic texts, and Syriaca language closely related to Aramaicto explore early Christian sources like the Old Syriac Gospels. Instructed by these ancient literatures and no longer limited to what the Greek Gospels said, I began to understand Jesus on his own terms rather than in the categories of conventional scholarship and theology. I was stunned to discover that not only the inspiration behind Jesus teachings, but also its actual contentpoint by pointwas drawn directly from Jewish sources. A portrait of Jesus as an inspired rabbi with an exclusively Jewish agenda began to emerge. I started to see a completely new meaning in baptism, anointing the sick, the Lords Prayer, the Eucharist, and resurrection. It became clear to me that everything Jesus did was as a Jew, for Jews, and about Jews.

I became part of the reevaluation of Jesus and Judaism. The basic fact that Jesus was Jewish is now fairly well established within scholarship and popular writing. The previous work of W. D. Davies, Asher Finkel, and Samuel Sandmel is a highly regarded part of the critical canon. By placing Jesus in his Jewish context they helped to overturn the once fashionable notion that the New Testament illuminated the contours of early Christian faith in Jesus, but taught us nothing important about the man himself.

Thanks to these and other penetrating studies, and a wealth of literary and archeological evidence that has accumulated since World War II, Jesus has emerged today as a truly historical figure. New evidence ranges from the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and fourth-century Gnostic gospels to the excavations of the Temple of Jerusalem, the tomb of the high priest Caiaphas, the city of Sepphoris, and a number of Galilean settlements, including Nazareth and Capernaum. These discoveries have added startling detail and depth to our understanding of religious culture at the dawn of the Common Era and shed bold new light on the life and character of Jesus.

A portrait of Jesus has emerged both in scholarship and popular literature from the discussion these finds have ignited. He becomes a witty philosopher, a Mediterranean peasant-savant descended from Greco-Roman heritage whose Judaism is an incidental fact of his ethnic background. This Jesus is fashionably separated from the traditional forms of religions against which intellectuals are perennially on their guard. The portrayal that has frequently emerged from The Jesus Seminar is a case in point: it has explored intriguing possibilities and sparked much useful controversy and debate, yet it fails to grapple with the complex issue of Jesus own religious orientation as a Jew. In that regard, the historical Jesus who has emerged in recent years is as flawed as the venerated images of Christ from Renaissance art or glowing hagiographies by sectarian theologians.

For the past decade, I have felt that my colleagues in scholarship were isolating and analyzing the pieces of Jesus life, but that no one was putting them together into a coherent whole. That is what I attempt to do in this book.

Next page