Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

F OR C AROL AND B ECCA

Most men, the herd, have never tasted solitude. They leave father and mother, but only to crawl to a wife and quietly succumb to new warmth and new ties. They are never alone, they never commune with themselves.

Hermann Hesse, Zarathustras Return , 1919

Set for yourself goals, high and noble goals, and perish in pursuit of them! I know of no better life purpose than to perish in pursuing the great and the impossible: animae magnae prodigus .

Friedrich Nietzsche, Notebook, 1873

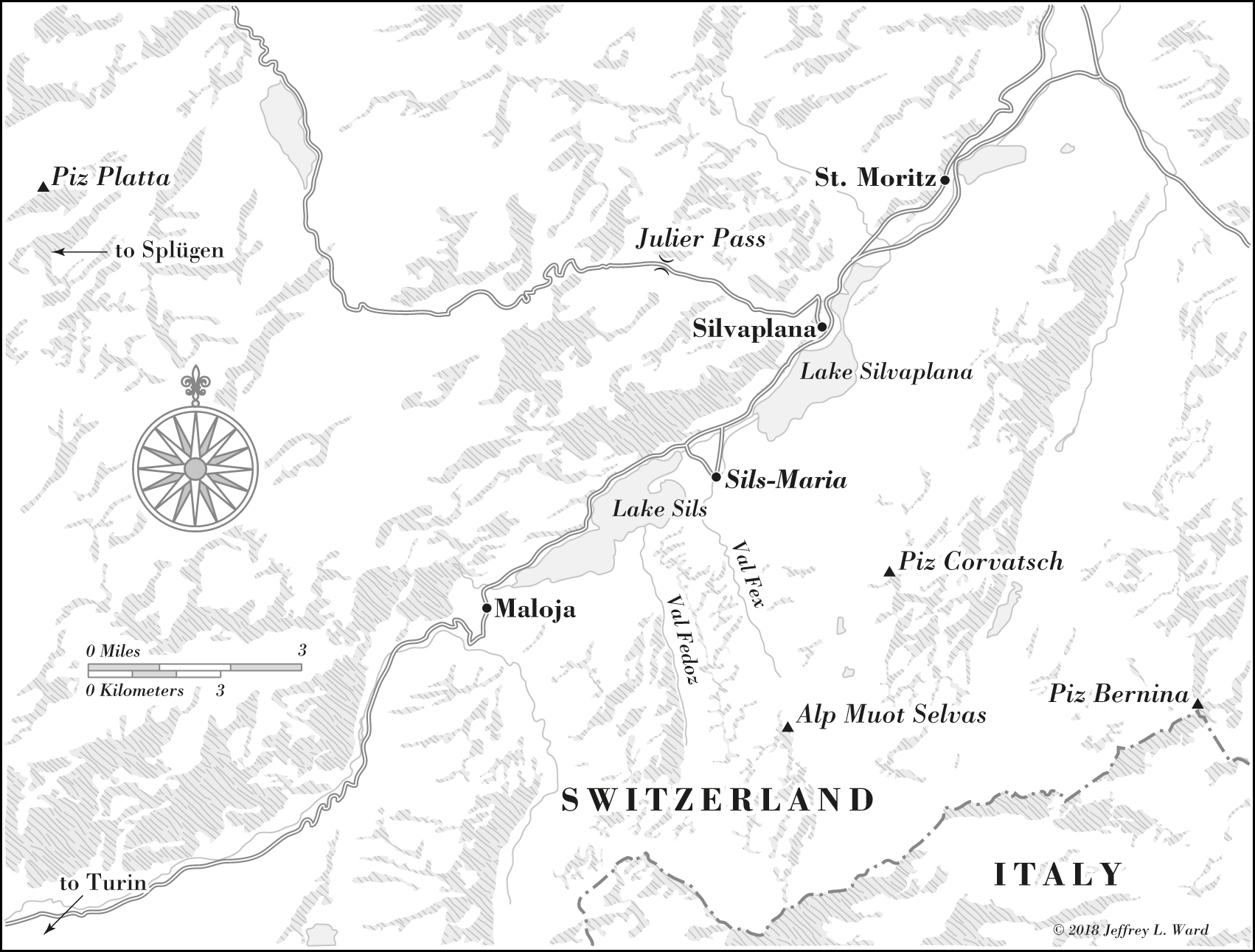

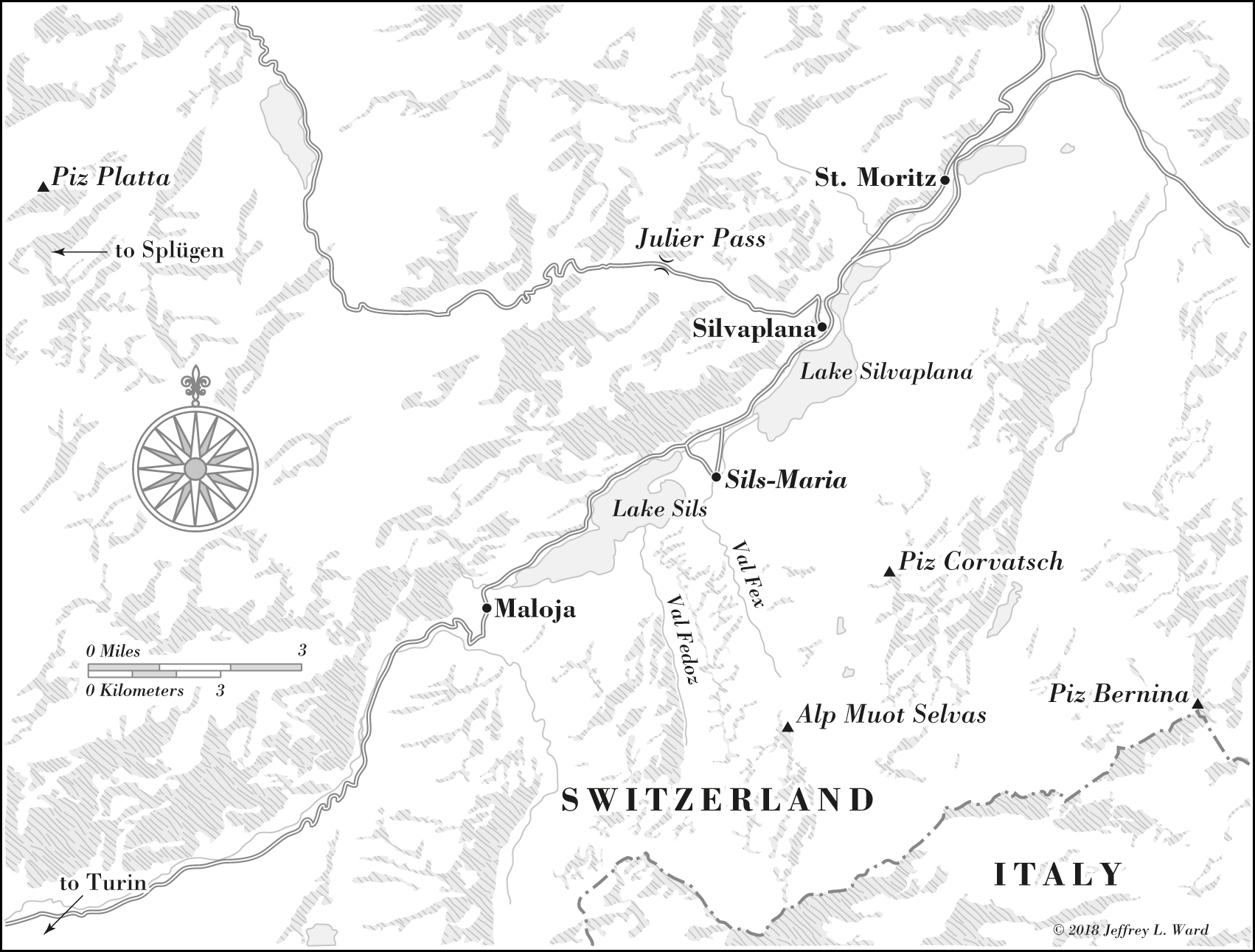

I t took me six hours to summit Piz Corvatsch. This was Friedrich Nietzsches mountain. The summer fog that hangs low in the morning had all but disappeared, exposing the foothills a mile below. I came to rest on a well-worn slab of granite and appreciated how far Id come. For a moment I looked down on Lake Sils, at the shimmering base of Corvatsch, an aquamarine mirror that stretched across the valley and doubled the landscape that was, I thought, already impossibly grand. Then the last of the clouds burned away, and Piz Bernina emerged in the southeast. In fact, I hadnt gone all that far. Bernina, the second-highest point in the Eastern Alps, is Corvatschs parent, the culminating point in a ridge that runs north to south, bisecting two massive glacial valleys. After the twenty-eight-year-old Johann Coaz first scaled its peak in 1850, he wrote, Serious thoughts took hold of us. Greedy eyes surveyed the land up to the distant horizon, and thousands and thousands of mountain peaks surrounded us, rising as rocks from the glittering sea of ice. We stared amazed and awe-struck across this magnificent mountain world.

I was nineteen. Parent mountains had a certain power over me. Looming or distant, the parent is the highest peak in a given range, the point from which all other geological children descend. I had been drawn to the Alps, to the hamlet of Sils-Maria, the Swiss village that Nietzsche called home for much of his intellectual life. For days, I wandered the hills that hed traversed at the end of the nineteenth century, and then, still trailing Nietzsche, I went in search of a parent. Piz Corvatsch, at 11,320 feet, casts a shadow over its children, the mountains that encircle Sils-Maria. Across the valley: Bernina. Three hundred miles to the west, at the French border of this magnificent mountain world, stands Berninas far-removed progenitor, Mont Blanc. After thatabsurdly remote, estranged, and omnipresentrests Everest, nearly twice the size of its French child. Corvatsch, Bernina, Mont Blanc, Everestthe road to the parent is, for most travelers, unbearably long.

Nietzsche was, for most of his life, in search of the highest, routinely bent on mastering the physical and philosophical landscape. Behold, he gestures, I teach you the bermensch . This Overman, a superhuman ideal, a great height to which an individual could aspire, remains an inspiration for an untold number of readers. For many years I thought the message of the bermensch was clear: become better, go higher than you presently are. Free spirit, self-conqueror, nonconformistNietzsches existential hero terrifies and inspires in equal measure. The bermensch stands as a challenge to imagine ourselves otherwise, above the societal conventions and self-imposed constraints that quietly govern modern life. Above the steady, unstoppable march of the everyday. Above the anxiety and depression that accompany our daily pursuits. Above the fear and self-doubt that keep our freedom in check.

Nietzsches philosophy is sometimes pooh-poohed as juvenilethe product of a megalomaniac that is perhaps well suited to the self-absorption and navet of the teenage years but best outgrown by the time one reaches adulthood. And its true, many readers on the cusp of maturity have been emboldened by this good European. But there are certain Nietzschean lessons that are lost on the young. Indeed, over the years Ive come to think that his writings are actually uniquely fitted for those of us who have begun to crest middle age. At nineteen, on the summit of Corvatsch, I had no idea how dull the world could sometimes be. How easy it would be to remain in the valleys, to be satisfied with mediocrity. Or how difficult it would be to stay alert to life. At thirty-six, I am just now beginning to understand.

Being a responsible adult is, among other things, often to resign oneself to a life that falls radically short of the expectations and potentialities that one had or, indeed, still has. It is to become what one has always hoped to avoid. In midlife, the bermensch is a lingering promise, a hope, that change is still possible. Nietzsches bermensch actually his philosophy on the wholeis no mere abstraction. It isnt to be realized from an armchair or the comfort of ones home. One needs to physically rise, stand up, stretch, and set off. This transformation occurs, according to Nietzsche, in a sudden sentience and prescience of the future, of near adventures, of seas open once more, and aims once more permitted and believed in.

This book is about aims once more permitted and sought after, about hiking with Nietzsche into adulthood. When I first summited Corvatsch, I thought that the sole objective of tramping was to get above the clouds into open air, but over the years, as my hair has begun to gray, Ive concluded that this cannot possibly be the only point of hiking, or of living. It is true that the higher one climbs, the more one can see, but it is also true that no matter the height, the horizon always bends out of view.

As Ive grown older, the message of Nietzsches bermensch has become more pressing but also more confusing. How high is high enough? What am I supposed to be looking at or, more honestly, searching for? What is the point of this blister on my foot, the pain of self-overcoming? How exactly did I reach this particular mountaintop? Am I supposed to be satisfied with this peak? At the doorway of his thirties, Nietzsche suggested, Let the youthful soul look back on life with the question: what have you truly loved up to now, what has drawn your soul aloft? In the end, these are the right questions to ask. The project of the bermensch like aging itselfis not to arrive at any fixed destination or to find some permanent room with a view.

When you hike, you bend into the mountain. Sometimes you slip and hurtle forward. Sometimes you lose your balance and topple back. This is a story of trying to lean in just the right way, to lean ones present self into something unattained, attainable, yet out of view. Even slipping can be instructive. Something happens not at the top, but along the way. One has the chance, in Nietzsches words, to become who you are.

He who has attained to only some degree of freedom of mind cannot feel other than a wanderer on the earth though not as a traveler to a final destination: for this destination does not exist.