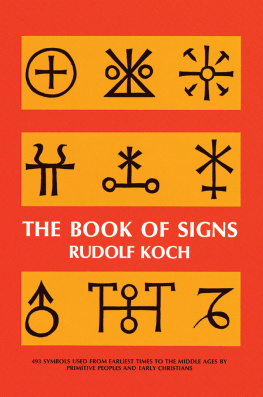

+ The Book of Signs +

which contains all manner of

symbols used from earliest times to the middle

ages by primitive

peoples and Early Christians

+ Collected drawn and explained

by Rudolf Koch

Translated from the German

by Vyvyan Holland

+

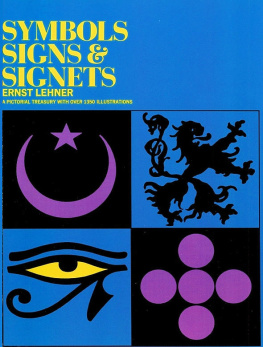

This Dover edition, first published in 1955, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the English translation originally published by the First Edition Club of London in 1930. This book belongs to the Dover Pictorial Archive Series. You may use the designs and illustrations for graphics and crafts applications, free and without special permission, provided that you include no more than ten in the same publication or project. (For permission for additional use, please write to Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501.) However, republication or reproduction of any illustration by any other graphic service whether it be in a book or in any other design resource is strictly prohibited.

Note

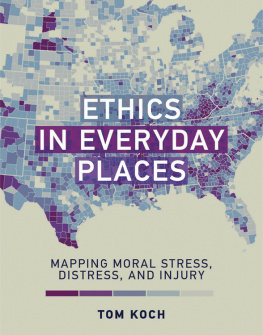

Students of modern printing will be aware that Rudolf Koch is an outstanding personality in the modern development of the graphic arts in Germany, and has achieved fame as a type-designer, calligrapher, artist and book-binder.::::The present translation of his Book of Signs contains 493 symbols, used from ancient times up to the middle ages, which have been collected by Koch and his friends from carvings, inscriptions and manuscripts.

Note

Students of modern printing will be aware that Rudolf Koch is an outstanding personality in the modern development of the graphic arts in Germany, and has achieved fame as a type-designer, calligrapher, artist and book-binder.::::The present translation of his Book of Signs contains 493 symbols, used from ancient times up to the middle ages, which have been collected by Koch and his friends from carvings, inscriptions and manuscripts.

Among them are Byzantine monograms, the signs of the Cross, the Holy initials, stonemasons signs, the signs of the four elements, and botanical, astrological and chemical signs. They have been redrawn and explained by Rudolf Koch himself, and cut on wood by Fritz Kredel. As readers will readily see, they have, in their present form at least, visual as well as symbolic beauty. A. J. A.

Symons

1. General signs.

The dot is the origin from which all signs start, and is their innermost essence. It was with this idea that the Masonic lodges of old expressed the secrecy of their guilds by means of the dot.

The vertical stroke represents the one-ness of God, or the Godhead in general; it also symbolizes power descending upon mankind from above, or, in the opposite direction, the yearning of mankind towards higher things.

In the horizontal stroke, on the other hand, we see the Earth, in which life flows evenly and everything moves on the same plane.

The angle, or the meeting of the celestial and the terrestrial.

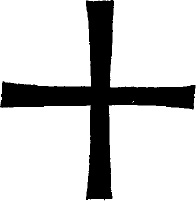

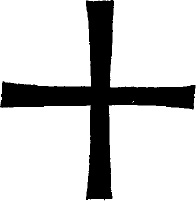

As they possess nothing in common, they touch, but do not cross one another, This sign represents the reciprocation between God and the World. In Masonic lodges of Middle Ages the right angle was the sign of Justice and Integrity.  In the sign of the Cross God and Earth are combined and ace in harmony. From two simple lines a complete sign has been evolved. The Cross is by far the earliest of all signs, and is found everywhere, quite apart from the conception of Christianity.

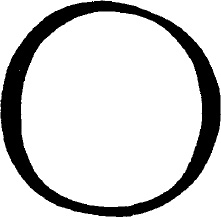

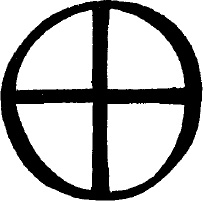

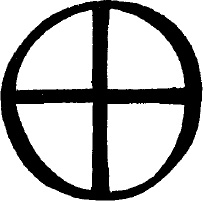

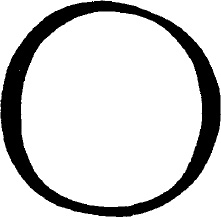

In the sign of the Cross God and Earth are combined and ace in harmony. From two simple lines a complete sign has been evolved. The Cross is by far the earliest of all signs, and is found everywhere, quite apart from the conception of Christianity.  The circle, being without beginning or end, is also a sign of God or of Eternity.

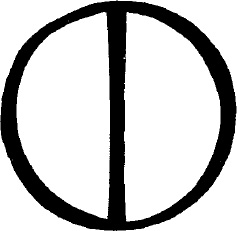

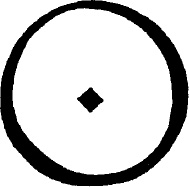

The circle, being without beginning or end, is also a sign of God or of Eternity.

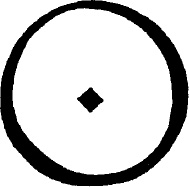

Moreover, in contrast with the next sign, it is a symbol of the sleeping eye of God: The Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.  The open eye of God, the purpose of Revelation: And God said, Let there be light.

The open eye of God, the purpose of Revelation: And God said, Let there be light.  The passive female element; what has been there from the beginning of all things. And God divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament.

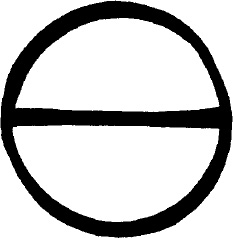

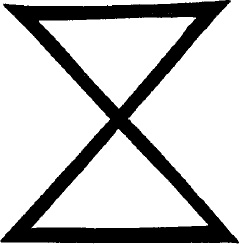

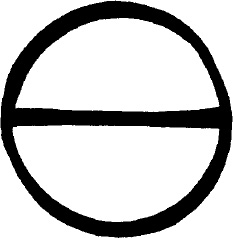

The passive female element; what has been there from the beginning of all things. And God divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament.  The active male element; what comes from on high; the effective clement in time.

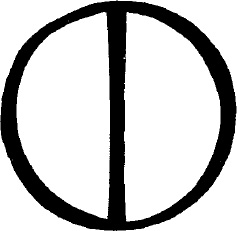

The active male element; what comes from on high; the effective clement in time.  As the male element pervades the female, so creation takes place, since everything belonging to the living world is compounded of the confluence of male and female.

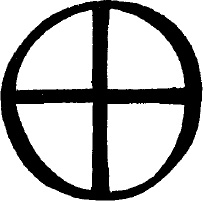

As the male element pervades the female, so creation takes place, since everything belonging to the living world is compounded of the confluence of male and female.  As the male element pervades the female, so creation takes place, since everything belonging to the living world is compounded of the confluence of male and female.

As the male element pervades the female, so creation takes place, since everything belonging to the living world is compounded of the confluence of male and female.

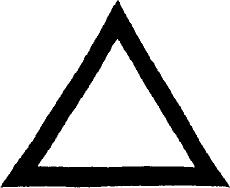

In remote ages in the East, and also in early northern mythology, this sign of the wheel-cross was a symbol of the Sun.  The triangle is an ancient Egyptian emblem of the Godhead, and also a Pythagorean symbol for wisdom. In Christianity it is looked upon as the sign of the triple personality of God. Again, in distinction from the next sign, it is another sign for the female element, which is firmly based upon terrestrial matters, and yet yearns after higher things. The female is always earthly in its conception.

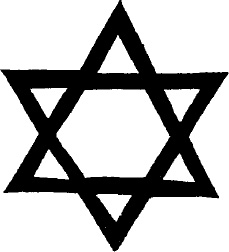

The triangle is an ancient Egyptian emblem of the Godhead, and also a Pythagorean symbol for wisdom. In Christianity it is looked upon as the sign of the triple personality of God. Again, in distinction from the next sign, it is another sign for the female element, which is firmly based upon terrestrial matters, and yet yearns after higher things. The female is always earthly in its conception.  Both figures now start moving towards one another, and as they touch each other with their apexes they form another figure, entirely new in appearance, without, however, either of the original figures being damaged or interfaced with in any way.

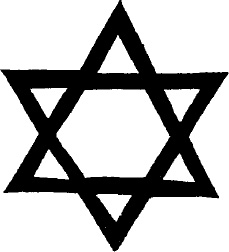

Both figures now start moving towards one another, and as they touch each other with their apexes they form another figure, entirely new in appearance, without, however, either of the original figures being damaged or interfaced with in any way.  When, however, they pass through one another, the nature of both is fundamentally altered and, as it appears, is practically obliterated.

When, however, they pass through one another, the nature of both is fundamentally altered and, as it appears, is practically obliterated.

This Dover edition, first published in 1955, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the English translation originally published by the First Edition Club of London in 1930. This book belongs to the Dover Pictorial Archive Series. You may use the designs and illustrations for graphics and crafts applications, free and without special permission, provided that you include no more than ten in the same publication or project. (For permission for additional use, please write to Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501.) However, republication or reproduction of any illustration by any other graphic service whether it be in a book or in any other design resource is strictly prohibited.

This Dover edition, first published in 1955, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the English translation originally published by the First Edition Club of London in 1930. This book belongs to the Dover Pictorial Archive Series. You may use the designs and illustrations for graphics and crafts applications, free and without special permission, provided that you include no more than ten in the same publication or project. (For permission for additional use, please write to Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501.) However, republication or reproduction of any illustration by any other graphic service whether it be in a book or in any other design resource is strictly prohibited.  The dot is the origin from which all signs start, and is their innermost essence. It was with this idea that the Masonic lodges of old expressed the secrecy of their guilds by means of the dot.

The dot is the origin from which all signs start, and is their innermost essence. It was with this idea that the Masonic lodges of old expressed the secrecy of their guilds by means of the dot.  The vertical stroke represents the one-ness of God, or the Godhead in general; it also symbolizes power descending upon mankind from above, or, in the opposite direction, the yearning of mankind towards higher things.

The vertical stroke represents the one-ness of God, or the Godhead in general; it also symbolizes power descending upon mankind from above, or, in the opposite direction, the yearning of mankind towards higher things.  In the horizontal stroke, on the other hand, we see the Earth, in which life flows evenly and everything moves on the same plane.

In the horizontal stroke, on the other hand, we see the Earth, in which life flows evenly and everything moves on the same plane.  The angle, or the meeting of the celestial and the terrestrial.

The angle, or the meeting of the celestial and the terrestrial.  In the sign of the Cross God and Earth are combined and ace in harmony. From two simple lines a complete sign has been evolved. The Cross is by far the earliest of all signs, and is found everywhere, quite apart from the conception of Christianity.

In the sign of the Cross God and Earth are combined and ace in harmony. From two simple lines a complete sign has been evolved. The Cross is by far the earliest of all signs, and is found everywhere, quite apart from the conception of Christianity.  The circle, being without beginning or end, is also a sign of God or of Eternity.

The circle, being without beginning or end, is also a sign of God or of Eternity. The open eye of God, the purpose of Revelation: And God said, Let there be light.

The open eye of God, the purpose of Revelation: And God said, Let there be light.  The passive female element; what has been there from the beginning of all things. And God divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament.

The passive female element; what has been there from the beginning of all things. And God divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament.  The active male element; what comes from on high; the effective clement in time.

The active male element; what comes from on high; the effective clement in time.  As the male element pervades the female, so creation takes place, since everything belonging to the living world is compounded of the confluence of male and female.

As the male element pervades the female, so creation takes place, since everything belonging to the living world is compounded of the confluence of male and female.  The triangle is an ancient Egyptian emblem of the Godhead, and also a Pythagorean symbol for wisdom. In Christianity it is looked upon as the sign of the triple personality of God. Again, in distinction from the next sign, it is another sign for the female element, which is firmly based upon terrestrial matters, and yet yearns after higher things. The female is always earthly in its conception.

The triangle is an ancient Egyptian emblem of the Godhead, and also a Pythagorean symbol for wisdom. In Christianity it is looked upon as the sign of the triple personality of God. Again, in distinction from the next sign, it is another sign for the female element, which is firmly based upon terrestrial matters, and yet yearns after higher things. The female is always earthly in its conception.  Both figures now start moving towards one another, and as they touch each other with their apexes they form another figure, entirely new in appearance, without, however, either of the original figures being damaged or interfaced with in any way.

Both figures now start moving towards one another, and as they touch each other with their apexes they form another figure, entirely new in appearance, without, however, either of the original figures being damaged or interfaced with in any way.  When, however, they pass through one another, the nature of both is fundamentally altered and, as it appears, is practically obliterated.

When, however, they pass through one another, the nature of both is fundamentally altered and, as it appears, is practically obliterated.