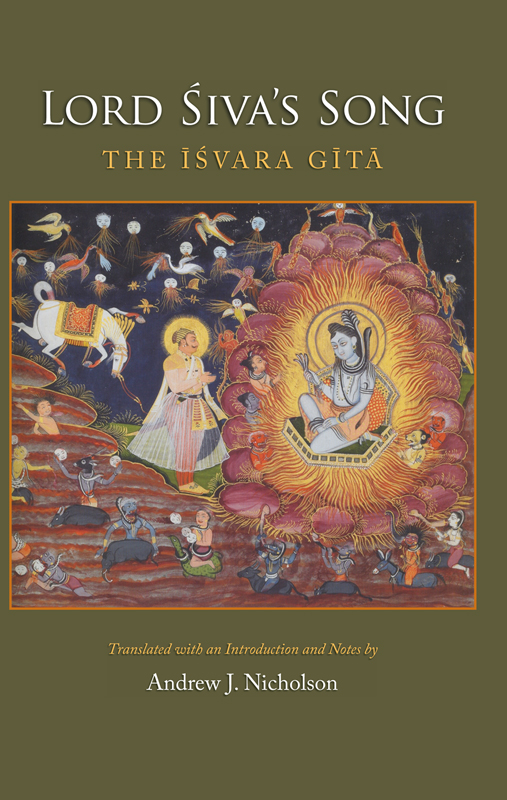

LORD IVAS SONG

LORD IVAS SONG

The vara Gt

Translated with an Introduction and Notes by

Andrew J. Nicholson

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

Cover art: Prince Subuddhi in the Forest of Illusion (folio 35 from the Suraj Prakash), accession number RJS1660, used with permission of Mehrangarh Museum Trust, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India, and His Highness Maharaja Gaj Singh of Jodhpur.

Published by

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

Albany

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact

State University of New York Press

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Laurie Searl

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Puranas. Kurmapurana. Isvar-gita. English.

Lord Sivas Song : the Isvara Gita / Translated with an introduction and notes by Andrew J. Nicholson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

Translated from Sanskrit.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5101-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

I. Nicholson, Andrew J. II. Title.

BL1140.4.K8742I8813 2014

294.5925dc23

2013020385

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the memory of Shri Narayan Mishra

yasya deve par bhaktir yath deve tath gurau

tasyaite kathit hy arth prakante mahtmana

These matters described by the great one

reveal themselves to the person

who shows the highest love toward god,

and as toward god, toward his own teacher.

vetvatara Upaniad 6.23

Contents

Acknowledgments

The quest for liberation through yoga in medieval India, although sometimes depicted as a solitary endeavor, was more often a project involving an entire community of teachers and disciples. The same is true of the quest to complete a book such as this one. I have benefited enormously from the guidance and friendship of many scholars, only a few of whom I have the space to acknowledge here. First, I wish to offer thanks to my teachers in the United States and in India, especially to Shri Narayan Mishra, who helped me with this translation but passed away before publication.

I am very grateful to Stony Brook University, which granted me a semester research leave in 2009 to begin this project, and which also awarded me an FAHSS research grant to travel to Varanasi in 2011. Mario Piantelli was very kind to make his excellent Italian translation of the vara Gt available to me in digital form. The online text of the Krma Pura and other Puras provided by the Gttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages (GRETIL) was also an important digital resource. My expert colleagues David Buchta, Whitney Cox, James Fitzgerald, Deven Patel, and Travis Smith read parts of my manuscript and offered invaluable advice. I presented parts of the introductory section of this book to audiences at the American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting in 2010, the Freie Universitt Berlin Zukunftsphilologie Seminar in 2011, and the McGill University Faculty of Religious Studies Lecture Series in 2012. Their spirited, insightful questions have led me to refine my interpretations of the vara Gt and of Pupata philosophy. The students who read drafts of this work in undergraduate seminars with me at Stony Brook University offered suggestions to improve some of my unclear and ungainly translations. Finally, I thank my family, Claudia Misi, Silvia Nicholson, Marlene Nicholson, Norman Nicholson, and Elizabeth Nicholson, who have always sustained me with their love and encouragement.

Introduction

The vara Gt (Lord ivas Song) is a philosophical poem that conveys the teachings of the Pupatas, a group of iva worshippers who would have a profound and lasting influence on the development of Hinduism. Since its composition in the eighth century CE, it has been an inspiration to generations of philosophers, devotees, and yogis in India. Like its famous predecessor, the Bhagavad Gt (Song of Lord Ka), it goes beyond mere philosophical theory to describe a regimen of spiritual exercises to achieve self-transcendence and absolute freedom. These spiritual exercises, the Pupata Yoga, are a regimen of ethical discipline, breath control, physical postures, and mental concentration through which the yogi attains divine knowledge, power, and liberation. Pupatas are not content just to know god. The ultimate goal of Pupata Yoga is to become godto attain Lord ivas majestic power and wisdom in this very lifetime through mental absorption and union with him, the Lord of Yoga.

The proliferation of many different practices in the globalized yoga of the 20th and 21st centuries has led modern yogis to great uncertainty about what the final goal of yoga practice is: Is it stress relief? Peace of mind? Self-actualization? Nirva? Many teachers today describe Patajalis Yoga Stras, an influential text compiled between the second and fifth centuries CE, as the authoritive set of guidelines for yoga practice. But examination of Patajalis work reveals that many of the central ideas and practices of yoga as understood in later times are absent. One notable difference is Patajalis relative lack of interest in physical postures (sanas), the main focus of practice for many modern yogis. Another surprise for some Hindus might be the place of god (vara) in Patajalis Yoga Stras. Although often described as the classical Hindu yoga, worship of and meditation on god is according to Patajali a mere preliminary practice to the highest form of yoga.most Hindus, for whom god-absorption is the highest yogic practice.

The vara Gt, Lord ivas Song, shows some influence from Patajalis eight-limbed (aga) yoga. According to this later text, however, Patajalis highest form of mental absorption (samdhi) is a lower yoga, below absorption in god. The vara Gt also shares many concepts and themes with the famous Bhagavad Gt, composed some six centuries earlier. The most obvious difference between these two texts is the god who presents their teachings. In the Bhagavad Gt, it is Ka, in disguise as a charioteer, who instructs the great warrior Arjuna on the subtleties of philosophy and sacred duty (dharma). In the vara Gt it is iva as Paupati, Master of Beasts, who instructs a group of sages about the highest truth and the means to realize it through the practice of yoga. iva says that he himself is supreme, the source of creation for all other gods, and the ultimate focus of yogic concentration. In the popular imagination and especially among non-Hindus, iva is regarded as the god of destruction. However, according to the Pupatas who composed the vara Gt, he is something much more: the creator of the universe and the ultimate source of worldly bondage and liberation.

The Historical Background of the vara Gt

The earliest Hindu holy texts are the Vedas, composed in Sanskrit beginning in approximately 1500 BCE. For many Hindus, the Vedas are the absolute scriptural authority. According to traditional interpretation, the Vedas are eternal and beyond human authorship, received by ancient seers who spoke and memorized the words of the Vedas. Indeed, the word scripture is misleading insofar as the Vedas were oral texts not written down until hundreds of years after their composition. Scholars of the Vedas made a fundamental distinction between the eternal Vedas and other texts that were composed by human authors. In this second category are included the Bhagavad Gt and vara Gt, both attributed to the sage Vysa. Although considered an omniscient seer, Vysas texts and those composed by other great sages were not considered to have the same level of authority as the eternal Vedas. They were labeled traditional (