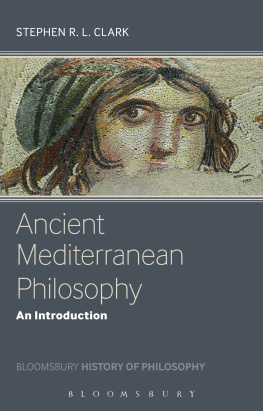

Ancient Mediterranean Philosophy

BLOOMSBURY HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY

Series editor: Michael Beaney, University of York, UK.

The Bloomsbury History of Philosophy series offers concise and accessible introductions to the key periods in the history of philosophical thought. Designed specifically to meet the needs of undergraduate students, each book provides a comprehensive historical survey of the period and introduces all the key themes and thinkers. The series builds to give a thorough overview of the whole history of this fascinating subject.

Forthcoming in the series:

Medieval Philosophy, Gyula Klima

Seventeenth Century Philosophy, Pauline Phemister

BLOOMSBURY HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY

Ancient Mediterranean Philosophy

An Introduction

STEPHEN R. L. CLARK

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 175 Fifth Avenue |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10010 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

First published 2013

Stephen R. L. Clark, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Stephen R. L. Clark has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ePub ISBN: 978-1-4411-4754-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clark, Stephen R. L.

Ancient Mediterranean philosophy: an introduction/Stephen R. L. Clark.

p. cm. (Bloomsbury history of philosophy)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-1-4411-0188-4 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4411-2359-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4411-4886-5 (ebook pdf: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4411-4754-7 (ebook epub: alk. paper)

1. Philosophy, Ancient. I. Title.

B171.C525 2012

180dc23

2012016911

Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai, India

CONTENTS

In composing this study of Ancient Mediterranean Philosophy, I have chosen to draw attention to other philosophical traditions than the Classical Greek and Latin, although we know much less about them. My working assumption is that people have engaged in philosophical enquiry and debate from the very earliest times, even if this activity was not always well distinguished from more poetic or free-wheeling speculation. I also assume that even the most parochial or xenophobic peoples have shared stories, arguments and intuitions with foreigners. It follows that any attempt to draw a line around Greek or Classical or even Mediterranean philosophy will fail: in the end, there are only people, of various tribes and cultures, changing and exchanging arguments and ideas about the world, themselves, and whatever lies beyond. It also follows that we cannot draw a line around what is Ancient, as distinct from Modern.

So can there really be a study of Ancient Mediterranean Philosophy? Can we even distinguish Philosophy from poetry, history, natural science, theology or proverbial wisdom? The Instructions of Ptahhotep (24142375 BC) were very much what later, philosophical moralists repeated: not to be greedy; be patient and attentive; do the job you find yourself doing. This may not count as philosophy for the argumentative, but more Mediterranean people agreed with aphorisms like that than any substantive doctrine. There is small reason even to suppose that every native Greek-speaker, or everyone who thought of himself/herself as Hellene, from Gadara in Palestine to Gades on the Atlantic coast of Spain, over all the centuries from Hesiod to the final fall of Byzantium (or whenever) shared any concept of the self, or the world, or what to have for breakfast. Kingsley may be wrong to say that it was people at Athens who invented the fiction of a united Greece. But he is right that there never was a united Greece, because so many Greeks [let alone the other peoples of that world] wanted very little to do with Athens (Kingsley 1999, p. 197).

Even if we speak only of the Golden Age of Athens, from the defeat of Persia through its own brief empire to the death of Alexander, we can only conclude that the Athenians were a disputatious people, agreeing on almost nothing. Diodorus Siculus (fl. 40 BC) thought the same was true of the Greeks in general:

The result of this is that the barbarians, by sticking to the same things always, keep a firm hold on every detail, while the Greeks, on the other hand, aiming at the profit to be made out of the business, keep founding new schools and, wrangling with each other over the most important matters of speculation, bring it about that their pupils hold conflicting views, and that their minds, vacillating throughout their lives and unable to believe at all with firm conviction, simply wander in confusion. It is at any rate true that, if a man were to examine carefully the most famous schools of the philosophers, he would find them differing from one another to the uttermost degree and maintaining opposite opinions regarding the most fundamental tenets. (Diodorus 2.29.3)

We may doubt that the barbarians were united either. But despite those caveats, there is still something to be said for trying to see things clearly and to see them whole, as this task was attempted around the Ancient Mediterranean. According to Chesterton, the whole object of history is to make us realize that humanity can be great and glorious, under conditions quite different and even contrary to our own (Chesterton 1923, p. 176). A properly hermeneutical philosophy may also help us to remember that we too will one day be considered ancient, and such fragments of our thought as may survive will be acknowledged only as anticipations of some newly approved idea.

Why pick on the Ancient Mediterranean? The answer is easy: the people of that Age are at once the immediate ancestors of Western, Orthodox and Islamic civilization, and yet as alien as the Hindu or Chinese. They are at once entirely Other and so familiar as to be forgotten. And though they disagreed with each other, vehemently and at length, outsiders may still be able to see some common themes (as our successors will see what assumptions we unconsciously accept).

The Mediterranean Sea our sea as the Romans called it is linked to the outer Ocean only through the straits of Gibraltar and to another inland sea, the Black Sea (also called the Euxine or the Pontus), through the Hellespont. Its two basins, eastern and western, are linked and divided by the Strait of Sicily. The gaps between the northern peninsulas and islands are conventionally distinguished as the Aegean, Adriatic, Ionian and Tyrrhenian Seas. The lands to the north of the Sea are mostly mountainous, bunched up by the northward movement of tectonic plates, which also explains the many volcanoes dotted around the region, and the earthquakes and tsunamis that could eliminate islands and coastal cities. The southern shores are a strip of fertile land north of the Atlas Mountains and the encroaching Sahara. Northern hill-tribes and Southern desert-dwellers were occasional and often unwelcome visitors (and played a part in the eventual end of the Ancient world). Civilized people mostly lived in poleis , communities of the more-or-less like-minded with central shrines and market places, cultivating their particular patch of land and trading around the Sea for what they could not grow or make themselves. As Momigliano observes (1975, p. 74), ancient travellers did not find it easy to go into the interior. There were mountain passes, and other river valleys than the Nile, including the Rhone, the Po and the Danube. But most trade and travel passed around the coasts. Civilized peoples could be indigenous, at least like the Athenians in their own perception, but were also often colonizers from Greece, Phoenicia or Lydia. Egypt was an exception: its territory reaching south into Africa, along the Nile, and its history into an otherwise forgotten past. The empires of Mesopotamia, especially the Assyrian and Persian, also encroached on the eastern end of the Sea, and there were established trade-routes out towards the East. But those living around the Sea were mostly guarded from too frequent invasions over the mountains or the deserts, and had forgotten enough of their past to be able to invent a novel future. Nor did they much believe the adventures of Hanno of Carthage or of Euthymenes, around the western coast of Africa, or of Pytheas past the Tin Islands: both the latter citizens of Phocaea in Ionia (see Kingsley 2003, pp. 24151).

Next page