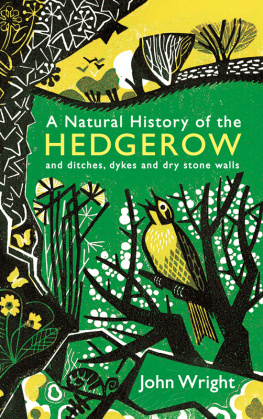

A Natural History of the

HEDGEROW

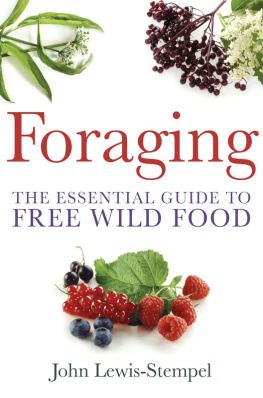

JOHN WRIGHT is a naturalist and leading expert on fungi. His most recent book, The Naming of the Shrew: A Curious History of Latin Names was published by Bloomsbury in 2014. His publications include books on how to forage in hedgerows and seashores, on the delights and perils of gathering fungi and mushrooms, and how to make your own booze, all published in the popular River Cottage Handbook series.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Mushrooms

River Cottage Handbook No. 1

Edible Seashore

River Cottage Handbook No. 5

Hedgerow

River Cottage Handbook No. 7

Booze

River Cottage Handbook No. 12

The Naming of the Shrew

A Curious History of Latin Names

A Natural History of the

HEDGEROW

and ditches, dykes and dry stone walls

JOHN WRIGHT

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

wc1x 9hd

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright John Wright, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84765 935 4

To my friend Richard Pearson, who is more at home in a hedge than most.

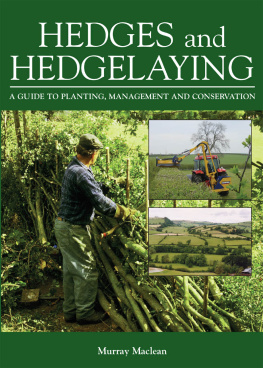

Summer hedgerows in West Dorset.

Introduction

A PREOCCUPATION WITH HEDGEROWS

I spend a large proportion of my time wandering along hedgerows, examining walls and banks and clambering in and out of ditches. Even a drive along a country road or more dangerously still a motorway, will have me glancing out of the window to see what is growing by the wayside. A favourite game in my family is to count how many cherry plum trees we can spot on a trip from our home in Dorset to, say, Oxford (147), though it could just as well be wild parsley stands or apple trees we are counting. Lethal as these distractions may be, at least they do not slow me down, but a walk from one end of 100 metre hedge to the other can take me half an hour and any companions soon get bored and walk on ahead. But arent you interested? I might ask rather pompously. Look at this elder tree thats had its bark rubbed away by a deer, or Heres an oak apple, lets see if the wasp has flown, or This plant will have you dead in half an hour if you eat it, and so on.

What interests me most are the mysteries plants I do not recognise at all, fungi that I can put a genus to but not a species, things that could be animal, vegetable or mineral. I would like to think that such an attitude is not unusual; after all, many of my friends are enthusiastic naturalists of one sort or another, but, sadly, I do not think that this is the case.

I often take people on mushroom and hedgerow forays and while a few can tell an elder from an alder they are in the minority. The people who join me do so to learn about wild foods; what can be found in hedgerow, wood, pasture and meadow that tastes pleasant, wont have them in A&E and are free. I duly oblige, but I try to show them more much more. I think that, on the whole, I am successful, though it is not always easy to tell. On a few occasions my success has been immediate and obvious. I am proud of what I do, though I take no great credit for it; it is just the everyday delight of an enthusiast, sharing the objects of his passion with others. I just slow people down and invite them to look.

For those who are willing to go slow, there is much to see; much more than might be imagined. Part III of the book, the largest part, covers the natural history of Britains hedges in some detail. It tells the stories of hawthorn and blackthorn, of oak and elm and a dozen more hedgerow trees, but also of those organisms that depend on them or cohabit with them. Some are obvious, like the endless stands of cow parsley that appear every spring, others are very much more subtle. The hawthorn, for example, supports dozens of microfungi, many micro-moths and macromoths, several galls and scores of other organisms.

This is what makes a walk along a hedgerow so much more than just a bit of exercise or a breath of fresh air. My particular interest is largely in hedgerow trees and plants and what may be called their diseases and symbionts organisms living in symbiosis. This may disappoint those with an interest in vertebrates, be they bird, bat or badger. I do, however, write of the relationships these animals have with their hedgerow habitat. Reptiles and amphibians barely get a mention except to acknowledge that they too can find a home in a hedge or wall.

Quite how unique hedges are to Britain is not sufficiently appreciated. For example, the tunnels sometimes formed by roadside hedges, notably in the south, are almost unknown in other parts of the world. I am fortunate in that where I live I can see half a dozen hedges just by glancing out of my office window at the hill above my village. Most people in Britain live in towns and may not see a rural hedge at close quarters from one year to the next (I was a townie once, so I mean no criticism). Those fabled visitors arriving from outer space would have, literally, a very different view. From the air the landscape is dominated not by towns and cities, not by roads and factories, not even by forest or bare heath, but by a coast-to-coast network of hedges and fields. They might assume that the entire population spent its time creating and tending this truly vast construction. Not so long ago, they would have been right.

Once a year or more, many of us become like those aliens for a few minutes. Returning from a holiday in Greece or Turkey or anywhere else, we see what they would see and it takes our breath away. Beautiful as our holiday destinations may be, they cannot compare to the lush, green patchwork visible beneath us as we take the descent to Gatwick, Heathrow or my personal favourite Exeter in Devon.

What, these extra-terrestrial visitors might wonder, are all those lengths of hedges for?

Religious observance? Installation art? Some among those who live on this island often wonder too. The answer is that there is no single use for a hedge, but many. It may simply be a way of controlling and sheltering stock; a means of protecting crops and stock from unwelcome animals or from theft; as a defence against soil erosion, or as a resource for timber, food and medicine. These are practical matters, but there are also more psychological and social issues, such as the demarcation of private property and privacy. Which of these are important at any one time and it may be several of them determine the fate and nature of the hedge. If a hedge ceases to be valued, then the land it is on is usually reclaimed and put to better use. For a thousand years hedgerows were almost entirely dispensed with in about half of England and Wales, after which they were widely replanted only, more recently, to be dispensed with all over again in many parts of the country.

Next page