ALSO BY ROBERT M. THORSON

Robert M. Thorson

Copyright 2005 by Robert M. Thorson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Walker Publishing Company, Inc.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry and Whiteside, Markham, Ontario L3R 4T8

104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

Exploring stone walls : a field guide to stone walls / Robert M. Thorson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Stone wallsNew EnglandHistory. 2. New England Antiquities. I. Title.

Some may know what they seek in school and church,

And why they seek it there; for what I search

I must go measuring stone walls, perch on perch.

Robert Frost, "A Star in a Stoneboat"

CONTENTS

The ideas for this book emerged as answers to questions asked of me since publication of my previous book, Stone by Stone, in 2002. About half came from those attending public lectures or listening to call-in radio shows. The other half were what I call "Dear Dr. Thorson" letters of inquiry sent to the Stone Wall Initiative, asking for suggestions and advice. People wanted to know what to do to get more information, where to go, and how to name stone walls. After a year or so of this, several booksellers suggested that I write a guide to New England stone walls.

Eventually I dropped what I was doing, began to compile and organize my answers, drove thousands of miles in search of stone, took over a thousand photographs, and gave serious thought to the naming of walls. Exploring Stone Walls is the result.

Thanks to everyone, especially the booksellers, who prompted and encouraged me to take the time to write the first "detective" book on stone-wall science. Once I got started, it became lots of fun. Thanks also to the innkeepers and friendly folk who put me up during my two-year odyssey around the back roads of New England. Thanks to my wife, Kristine Thorson, for allowing the family station wagon to be dedicated to the task and for navigating the way. Thanks to Rufus Frost and David Morse for reviewing an early version of the text, and to Kristin Lammi and Nick Bellantoni, for reviewing the stone-wall classification. Thanks to my agent, Lisa Adams, and to the staff at Walker & Company, particularly my editor, Jackie Johnson. Most importantly, thanks to the countless unnamed New Englanders whose collective wisdom about stone walls, freely given, is summarized in these pages.

Old stone walls are keys to the past. Each unlocks a separate door to the American experience. Some walls are tumbled ruins of rounded cobbles. Others are well-maintained historic fences, capped by quarried slabs. Some were built by the first colonial settlers. Others are being built today, in the folk-art traditions of the past.

Beneath such obvious differences are thousands of other clues to the who, what, where, when, and why of New England's stone walls, especially the old, tumbledown walls stranded in its parks, suburbs, and towns as if they were so many shipwrecks. This guide will show you how to use these clues to observe stone walls more carefully, whether from your kitchen window, your car, or outdoors as you touch, examine, scrutinize, and even smell them. This guide will also show you how to name and classify walls and other stone ruins, then use that knowledge to help understand your own favorite stone wall and how it compares to others in the region.

Anyone can become a stone-wall detective. No tools or special training are needed. Come join me as we follow the trail of clues that weaves back and forth into natural history, American history, geography, and landscape architecture.

If you don't know the age of a stone wall, there are ways to guess. Look at its lichen cover, at the spread of its base, at the graininess of surface stones, and for telltale signs of rebuilding; all are chronological clues. If you want to know a wall's original purpose, you can note how tall or wide it is, search for human tool marks on the stones, then probe for a rubble interior. To name a wall you will look for certain things, then match them to the diagnostic features of the book's classification system. To understand why any stone wall looks the way it does, you need to know three things: the composition of the local bedrock, the behavior of the glacier at that spot, and a simple version of the local cultural history.

As a stone-wall tourist, you may pay new attention to the walls in the backdrop of your vacation scenes. Or you might make a special trip to see the black-and-white zebra walls of Vermont's quartz-rich slate country; the dappled gray granite walls of southern New Hampshire; the gold-tinted lace walls on Martha's Vineyard; the orderly, straight-edged fieldstone walls within fifty miles of common borders between Connecticut, Rhode Island, and central Massachusetts, the epicenter of traditional New England stone walls. There are maps, lists, classification keys, and other materials to help you explore stone walls anywhere, and at whatever level of expertise you choose. Once you get the hang of it, you begin to see stone walls in many different ways, as scrapbooks of local history, habitats for furtive creatures, art galleries for lichens, ferns, icicles, and fallen leaves, and archives of a deep geological past.

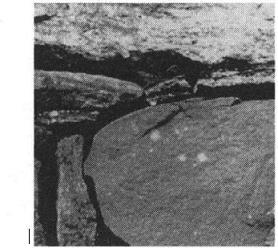

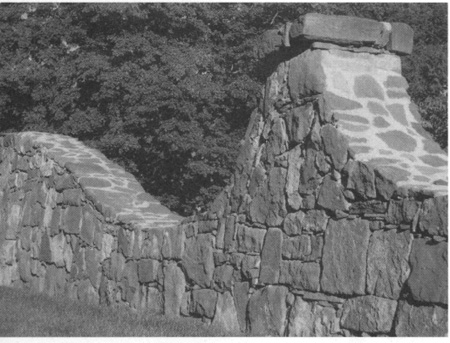

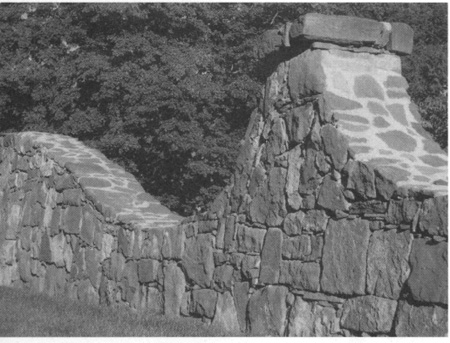

Ornate quarrystone wall, West Hartford, Connecticut

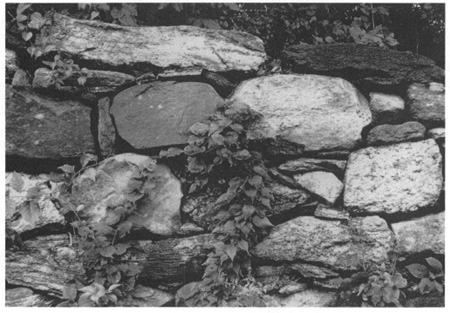

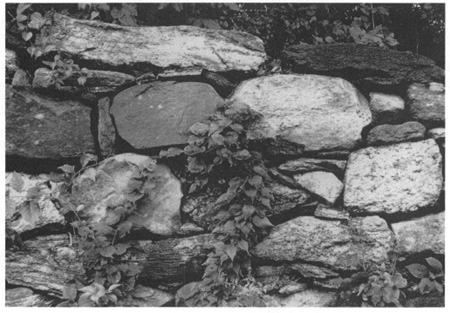

Variety in stone size, shape, and composition in a

local mix, eastern Connecticut

W hen we encounter a stone wall in the deep woods, we instinctively think of the place as being desolate. This is an illusion. Every stone in every wall is animated with life. On the outside, the stones are painted by microbes, stained by fallen leaves, and crusted by lichens. On the inside, especially near their bases, stone walls are filled with roots and humus, within which live a myriad of creeping creatures. Surrounding walls are the herbaceous vegetation and trees of the forest and human signs of suburban and rural life. Every wall is part of the broader habitat in which we, and other animals, live our lives.