Building Stone Walls

Excerpted from Stonework,

by Charles McRaven

CONTENTS

Why Build Stone Walls?

Why stone? Well, a better question might be, why not? For building or landscaping, you simply cant do better. Stone is weatherproof, ratproof, insectproof, and long lived. Stone is quietly elegant and looks expensive; whether you use it in rustic or formal designs, it signifies good taste.

In this age of disposables and throwaways, stone is also psychologically appealing; it represents strength and stability. Of course, its easier to work in wood, plastic, glass, steel, and even brick and cinder block, but once stone is in place it becomes a lifelong element of the landscape; it belongs. Building with stone is a tribute to permanence.

Stone has a negative aspect, however: Its heavy. Stone requires cement or gravel footings that are strong, deep, and wide, and sometimes youll need elaborate lifting devices to get stones up high enough for placement on walls. Being heavy, stone also is frequently dangerous to handle. Just as gravity and friction keep it in place, they can make positioning stone laborious and hazardous.

In addition, when compared with wood or cement, stone is difficult to shape, and setting stone is unforgiving work that requires great patience. With a helper, a good mason can lay about 20 square feet (1.8 sq m) a day. Some do 30 (2.7 sq m) or more, but good, tight, artistic work takes time time to select, fit, reject, shape, and mortar each stone.

Stonework is not for everyone. But everyone can learn from handling stone, enjoying the discipline, the craft, and the satisfaction that comes from artfully building a wall that will last for centuries.

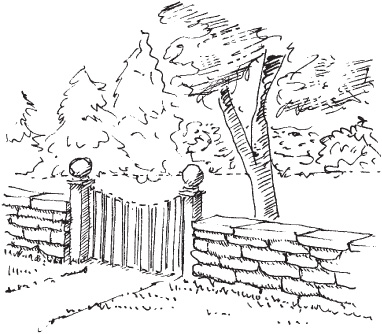

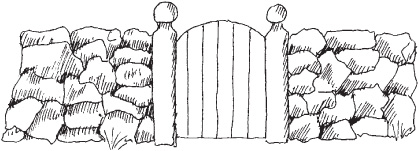

Freestanding stone walls are often used to mark a boundary or to act as an entryway to a private space, such as a garden.

Getting to Know Stone

The stone you choose to work with should match the environment in which you are placing it. Too often, people use cut stone or freshly quarried stone, or they choose a nonnative stone because they have seen it somewhere or picked it out of a magazine. Your stone should match native stone; if you cant find any native stone to work with, look for some that matches it as closely as possible. Weathered fieldstone is the most agreeable to see, because thats what you see in nature. You want character: A mossy, irregular piece of granite, a lichened sandstone, or an eroded limestone will appear to have been where it is for much of its millions of years of age. Even in formal gardens, the man-made symmetry must give the impression of age. Excessive shaping and smoothness, fresh cuts, geometric cuteness, wide mortar joints all destroy this feeling.

Sandstone and Quartzite

Sandstones and quartzites are the most versatile building stones. They range from coarse, soft, crumbly rocks to dense, fine-grained creek quartzites so hard that they ring when struck.

Sandstone is a good stone to learn on because it cuts well, occurs in layers, and is porous enough to age quickly after shaping. It comes in as many colors as sand itself grays, browns, whites, roses, and blues (the most common, though, are grays and browns) and is composed of fine sand particles fused together under great pressure. Many sandstones have a definite grain along them that can be split easily. Therefore, sandstone is best laid flat, the way it was formed. Set on edge, it may weather in such a way that the layers separate. The sandstone you may have access to could be soft or hard, weak or strong. In mortared work, the stone should be at least as hard as the mortar.

Sandstone usually splits into even thicknesses in nature, so the critical top and bottom surfaces are already formed. If any shaping is necessary, it may be nothing more than a bit of nudging on the face of each stone to give an acceptable appearance. When making your selection, of course, try to find stones that are already well shaped, thereby keeping any necessary shaping to a minimum. Any sandstone can be worked to the shape you desire, but theres a logical limit. If you spend all your available time shaping, then efficiency plummets.

Limestone

Limestone has always been a favorite stone for builders. Dense but not hard, it can be worked to almost any shape. Before concrete blocks were invented (around 1900), limestone was the accepted standard for commercial stonework.

Newly cut limestone has a slick surface that is unattractive; weathered, top-of-the-ground limestone, on the other hand, is often rough, fissured, pockmarked, and interesting. (In addition, limestone often houses fossil seashells, trilobites, and other traces of prehistoric life, which can add another interesting dimension to your wall.) If you have access only to fresh-cut limestone, however, take heart: Aging is a long process, but the newly cut faces will lose their fresh-cut look in five years or so.

Granite

Granites are generally rough-textured stones that are not naturally layered. When weathered, their exterior provides a welcoming environment for lichens and mosses. Strong and hard granites vary in color. Along the East Coast, the familiar light gray granite is plentiful. Formed principally of feldspar and quartz, its a favored landscaping stone. There are also dark blue, dark gray, greenish, and even pink granites.

If you use granite, try to find stones naturally endowed with the desired shapes, as they can be hard to shape. Granite can often be recycled from foundations, chimneys, and basements of abandoned buildings.

Stones to Avoid

If you have a limited supply of stones, try mixing types to give added texture to a wall and keep it from visually fading into the landscape.

Working with Mixed Lots

Shale, slate, and other soft, layered stones are not very good as building stones. Other odd stones, such as the hard and flashy quartz, are hard to work with and rarely look natural.

The Best Stone for Mortarless Walls

In drystone work that is, stonework without mortar both sandstone and limestone are ideal because of their evenly layered strata. The more bricklike the stones are in shape, the easier it is to lay drystone. And with the inevitable sprouting of plants from the crevices, these walls age well.

Finding a Source for Good Stone

Before you can work with stone, you have to get the stuff. And where you get it depends a lot on where you happen to be. However, whether you plan on buying stone from a stone lot or want to head out into the back woods of your property to collect loose rock, there are four points to remember that will simplify your task:

Because one criterion for good stone is that it be as native to the environment as possible, start your search close to home.

Because one criterion for good stone is that it be as native to the environment as possible, start your search close to home.

Especially when youre prospecting, look for usable shapes, such as a flat top and bottom, with the appearance youre looking for on what will be the stones face. When you find some, therell usually be more of the same nearby, because stone tends to fracture naturally along the same lines in a given area.

Especially when youre prospecting, look for usable shapes, such as a flat top and bottom, with the appearance youre looking for on what will be the stones face. When you find some, therell usually be more of the same nearby, because stone tends to fracture naturally along the same lines in a given area.

Because one criterion for good stone is that it be as native to the environment as possible, start your search close to home.

Because one criterion for good stone is that it be as native to the environment as possible, start your search close to home.