Building & Using Cold Frames

Charles Siegchrist

CONTENTS

Introduction

Imagine your Thanksgiving table graced with a beautiful salad of crisp baby lettuce, tangy onions, crunchy radishes, and your very own tomatoes.

While this may sound like the northern gardeners fondest fantasy, you can make it come true thorough the use of a simple, inexpensive cold frame.

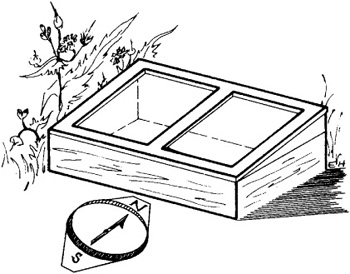

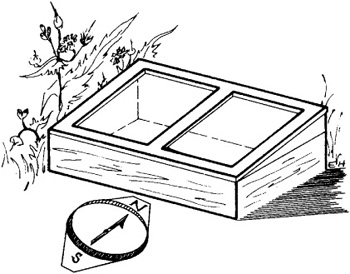

A cold frame is nothing more than a box of boards set on the ground outdoors and topped with a second-hand storm window, but its simplicity belies its usefulness.

Involving a days work with readily available materials and simple hand tools, construction of a cold frame is quick and economical. The cost of a cold frame no more than $50 will be repaid many times over in pleasure, pride, and plain good eating.

With a cold frame, you can stretch the growing season for salad greens up to three months in short-season areas. With escalating food prices it is easy to imagine the cash savings.

Perhaps more importantly, your fare will taste better. Instead of feigning contentment with insipid iceberg lettuce, you can enjoy succulent Buttercrunch and baby spinach leaves.

In addition to expanding the length of the growing season, a cold frame can increase the types of produce you can grow.

Selecting a Site

In order to trap the maximum amounts of heat and light, a cold frame should face south. Should this prove impractical for your location, a southeasterly exposure is preferred next. A site close to a south-facing wall will get extra heat and protection.

The ground on which the frame is to be set should be well drained, free of large stones and reasonably level. Placing the cold frame within your regular vegetable patch will save the bother of drawing in soil to fill the bottom. Such a location will also save many steps at transplanting time.

Choose the spot in the garden carefully so that the cold frame does not become a hindrance to routine cultivation. A location near perennial plants such as asparagus and rhubarb may serve well. Soil near such crops is usually rich and friable, and further, the location is out of the way of yearly garden chores such as rototilling.

Foundation

How ambitious are you?

A foundation for this cold frame is not essential for most uses. But an insulated foundation will retain heat in the cold frame, and permit you to use the frame even longer in both spring and fall.

If you decide to build one, plan on going down two feet or more with it, use concrete blocks, add 2-inch Styrofoam insulation on the outside and attach it to the blocks with plastic roofing cement. For most of us, this foundation isnt needed. In cold climates, or for the gardener needing maximum heat for the plants hes raising, the extra heat stored in the cold frame will be appreciated.

Materials

Cold frames may be built as grand or as humble as the owner desires. Plans given here are for a durable, low-budget model.

This is a portable structure which can be easily collapsed for storage in an area of about three feet by six feet by one foot.

The work should be a weekend project for anyone who has access to a basic collection of hand tools and the skill to use them.

The primary component of the cold frame is wood. In selecting the type of wood to be used, utmost consideration should be given to decay resistance. Being out in the weather most of the year and in direct contact with the soil, the wooden parts should be of species such as cedar, cypress, or redwood. These materials are listed in ascending order of cost.

If lumber of those types should prove unavailable or too expensive, consider using hemlock. It is an inexpensive, tough wood and should give good service despite its drawbacks.

Its shortcomings include knots as hard as steel, a tendency to crack and twist if improperly cured, and relative unattractiveness compared to such a lovely wood as redwood. Hemlock is rugged enough to see service as bridge planks on our Vermont back roads.

List of Materials

Whatever type of wood you select, you will need the following dimensions and quantities:

Amt | Dimension |

| 1 1 10 (cut into four pieces of 7; four pieces of 10; three pieces of 11) |

| 2 2 8 |

| 1 8 12 (cut into one piece of 69; two pieces of 35) |

| 1 4 3 (cut to 35) |

| 1 6 12 (cut into two pieces of 69) |

Your hardware needs for the project are as follows:

lb. | 6d common nails |

| 1 slotted wood screws |

| 12 weather stripping |

1 set | 4 T-hinges. These usually are sold with screws included. If not, buy a dozen 1 slot head wood screws as well. |

Tools Needed

Tools necessary for the job include a measuring tape, square, hammer, hatchet, saw, screwdriver and pencil. A bar of soap will be handy for easing the driving of screws. If you plan to use an old storm window, you will need a putty knife and glazier points. If you build your own window, get a chisel.

You will also need to get a transparent lid for the cold frame. Directions are given below for the construction of a lid 36 by 72 inches. A more durable and economically comparable substitute is a used storm window of those dimensions. Look for one at a garage sale, junk store, or the like. If you have a choice of storm windows, choose the one with the fewest panes of glass. It will cast fewer shadows on the growing plants.

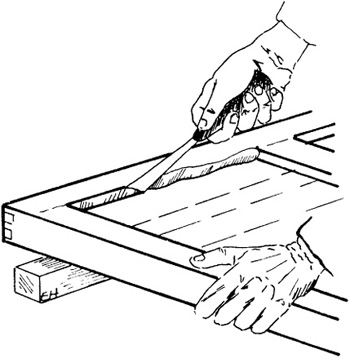

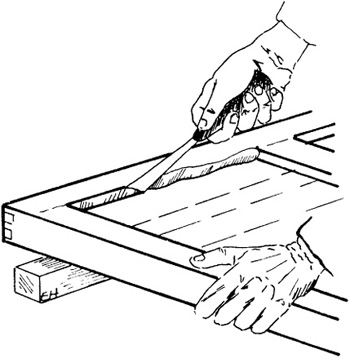

Finally, secure a quart of good quality wood preservative and an inexpensive small paint brush. Do not use creosote, as its fumes are toxic to plants. Ask your dealer for a stain or sealer suitable for the project. Cuprinol is a good choice.

Preparations

Assuming you have chosen to use an old storm window, scrape away all cracked and loose paint, and the putty if it is cracked and dry. Saturate the cleaned areas with wood preservative and allow ample drying time.

Check the recessed joint where wood meets glass. When the window is tilted in position atop the cold frame, these areas will tend to collect rainwater. Thus they deserve special attention now.

Look where the putty was for small, triangular pieces of metal which hold the glass in position. Each pane of glass should have at least two of these glazier points along each of its four sides. If more are needed insert them into the wooden part of the window with firm pressure from the tip of a screwdriver.

Once the glass is secured, ready some glazing compound. Knead a small wad of compound until it is soft and pliable. Using a putty knife work small dabs of the compound into the recess where glass meets wood until a uniform depth has been applied around the perimeter of the glass.

Starting at a corner of the pane, hold the putty knife at such an angle as to form a triangle of glazing compound that is flush to the top of the surface of the wood and extends about a inch out onto the glass. Steadily and evenly, draw the knife down the joint until a corner is reached. Reposition the knife and continue to the next corner, repeating until all the putty is new.