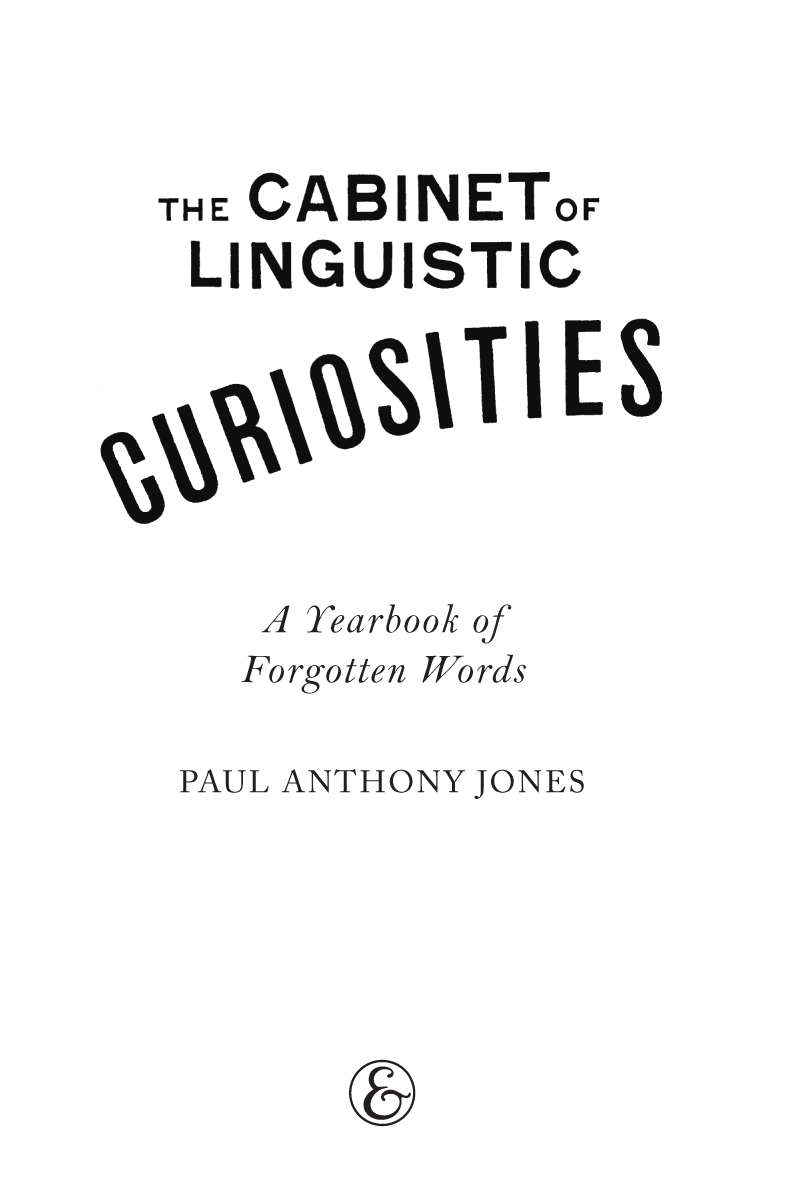

Jones - The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words

Here you can read online Jones - The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: La Vergne, year: 2017, publisher: Elliott & Thompson, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words

- Author:

- Publisher:Elliott & Thompson

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- City:La Vergne

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Kevin, with thanks

Londons Haymarket Theatre was packed to the rafters on the evening of 16 January 1749. An excitable audience had filled it to capacity after an advert in a local newspaper had promised a performance by a conjuror apparently able to transport himself from centre stage and into an empty wine bottle on a table nearby. The feat sounded too incredible to be true, for the very good reason that it was. The advertisement was a hoax.

Precisely who perpetrated it remains debatable, but when it became clear that a teleporting conjuror was not going to perform that night, one of the Haymarkets staff bravely came to the stage to explain that the performance would have to be cancelled and in response the audience erupted into a furious riot that all but destroyed the theatres interior. But this curious event did have a silver lining, at least: it is the origin of the bizarre and seldom-used word bottle-conjuror, which remains in place in the dictionary as a byword for a hoaxing prankster or charlatan.

The tale of the bottle-conjuror is just one of an entire years worth of historical and etymological stories that fill the pages of this book: dip into this Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities every day of the year, and youll be met with a curious or meaningful historical anniversary and an equally curious or long-forgotten word of the day, picked from the more obscure corners of the dictionary.

On the day on which flirting was banned in New York City, for instance, youll discover why to sheeps-eye someone once meant to look at them amorously. On the day on which a disillusioned San Franciscan declared himself Emperor of the United States, youll find the word mamamouchi, a term for someone who considers themselves more important than they truly are. And on the day on which George Frideric Handel completed his 259-page Messiah oratorio after twenty-four days of frenzied work, youll see why a French loanword, literally meaning a small wooden barrow, is used to refer to an intense period of work undertaken to meet a deadline. The English language, it seems, is vast enough to supply us with a word for all occasions and this linguistic Wunderkammer (skip ahead to 7 June for that one...) is here to prove precisely that.

I have been raiding these troves of long-lost linguistic treasure since 2013, when the @HaggardHawks Twitter account tweeted its first few obscure words and language facts. And Ive been tweeting daily nuggets of linguistic gold every day since, from random left-brain cluttering trivia (advance the letters of the word oui ten places through the alphabet and youll arrive at yes) to bizarre etymological curiosities (because you have to straddle it, bidet means pony in French). But alongside all those, Haggard Hawks tweets a daily Word of the Day: a typically strange or long-forgotten word that its hoped you will never have heard of before and may, for whatever reason, wish to add to your daily vocabulary. And it is that which brings us to the book youre now holding in your hands.

Partly a yearbook of obscure language and partly an annual of events and observances, by opening this Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities youll find both a word and a day to remember, every day of the year. Each one has its own dedicated entry here, on which a curious or notable event and an equally curious or notable word are both explored. And because there really is a word for all occasions, all 366 daily doses of linguistic interest tie in with each daily event, and vice versa.

So whatever date this book has found its way into your hands, lets get right to it: theres a whole years worth of linguistic curiosities waiting to be discovered.

quaaltagh(n.) | the first person you meet on New Years Day |

Proving there really is a word for everything, your quaaltagh is the first person you meet on New Years Day morning.

If you think that word doesnt look even remotely English, youre right: quaaltagh (pronounced quoll-tukh, with a rasping gh like the sound in loch) was borrowed into English from Manx, the Celtic language of the Isle of Man, in the early nineteenth century. Its roots lie in a Manx verb, quaail, meaning to meet or to assemble, as it originally referred to a group of festive entertainers who would come together to gambol from door to door at Christmas or New Year singing songs and reciting poems. For all their efforts, these quaaltagh entertainers would be invited inside for food and drink before moving on to the next house on their route.

If, as was often enough the case, all of that happened early on the morning of 1 January, then there was a good chance that the leader of the quaaltagh would be the first-footer of each household. As a result, a tradition soon emerged that the identity of the quaaltagh could have a bearing on the events of the year to come: dark-haired men were said to bring good luck, while fair-haired or fair-complexioned men (or, worst of all, fair-haired women) were said to bring bad luck a curious superstition said to have its origins in the damage once wreaked by fair-haired Viking invaders.

Eventually, the tradition of door-to-door New Years Day gambolling disappeared (presumably because everyone is feeling far too delicate the morning after the night before), but the tradition of the quaaltagh being your luck-bringing first encounter on the morning of New Years Day, either inside or outside your house, has remained in place in the dictionary.

fedifragous(adj.) | promise-breaking, oath-violating |

If you made a New Years resolution only to ditch the gym for a box of chocolates or an afternoon in the pub on 2 January, then the word you might be looking for is fedifragous a seventeenth-century adjective describing anything or anyone that breaks an oath or a promise, or reneges on an earlier agreement.

Fedifragous combines two Latin roots: foedus, meaning treaty or contract, and frangere, meaning to break. Foedus is a common ancestor of a clutch of more familiar words like confederate, federal and federation, while it is from frangere that the likes of fragment, fragile and fraction are all descended as well as an entire vocabularys worth of more obscure and equally broken words:

confraction (n.) a smashing or crushing, a breaking up into small pieces

effraction (n.) a burglary, a house-breaking

effractive (adj.) describing anything broken off something larger

irrefrangible (adj.) incapable of being broken

ossifragous (adj.) powerful enough to break bone

Along similar lines, ossifrage literally bone-breaker is an old name for the lammergeyer, an enormous mountain-dwelling eagle known for its habit of smashing bones by dropping them from a great height and then devouring the shards. And even the humble saxifrage plant can take its place on this list: its name derives from the Latin

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words»

Look at similar books to The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: a Yearbook of Forgotten Words and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.